As a child, like many others, I loved to play in the mud. We had a “sandpile” next to our barn that was about 25% sand with the rest dirt, which is to say it was mud as it was in the north shadow of our big, old, red barn. I would spend hours playing “war” with my tiny green lead and plastic soldiers (the metal figures from my older siblings and the plastic ones that were given to me for Christmas… an unusual gift for a Mennonite/Anabaptist young boy). Making mountains and digging trenches in the mud was endless fun and assured me that when I came in from play I was guided directly to the bathtub — usually with a scolding from my older sisters or mother.

The McAllens of Mississippi

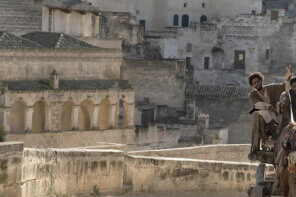

But our farm also had grass, trees, and green fields of tasseled corn along with fields of wheat and oats. The Mississippi farm owned by the McAllens in Mudbound has none of those. It consists of a bleak plank house surrounded by fields of mud and brown cotton. Mud comes up to their front porch and surrounds their outhouse. It soils their shoes and clothes, and it deposits into their hair and skin. It signifies that they live at the bottom of white society. McAllen’s home is little better than that of the sharecroppers they use to eke a living out of their farm. Almost the entire movie is gray/brown/black and grim, but portrayed with a dramatic arc that is not easily foretold.

An Opaque Opening

The film starts with a puzzling burial scene, which was intense but ended with the screen so dark I was guessing as to what was happening. (And do they bury people in eight foot deep graves in Mississippi?) During the scene (dramatically shot at its conclusion with a raging thunderstorm filling the grave with water and… mud) we get a confusing introduction to the film with Jamie McAllen’s voice-over — one of many voice-overs in this film. Then we see the following day’s feeble funeral — the crux of the film — followed by the entire story unfolding in flashback. We hear the voice-overs of “31 year old virgin” Laura (Carey Mulligan of An Education and Suffragette) who explains how she came to be courted and married to the unexciting farmer Henry McAllen (Jason Clarke of Zero Dark Thirty) and then became resigned to his “mudbound” farm (Laura says “I dreamed in brown”). And we meet Henry’s dashing younger brother Jamie (Garrett Hedlund) who goes off to WWII to seek fame and honor.

A parallel story unfolds of one of Henry’s sharecropper families, the Jacksons. They have a barely-adult son Ronsale (Jason Mitchell of Straight Outta Compton) whose parents are portrayed wonderfully by Rob Morgan and Golden Globe/Academy Award Nominee Mary J. Bilge. Ronsale also enlists in the Army and, for the first time, goes to a continent where he is not judged primarily for his skin color. Ronsale and Jamie both experience the horrors of war (we see brief glimpses) but also the love — both emotional and physical — of the grateful liberated populace.

A parallel story unfolds of one of Henry’s sharecropper families, the Jacksons. They have a barely-adult son Ronsale (Jason Mitchell of Straight Outta Compton) whose parents are portrayed wonderfully by Rob Morgan and Golden Globe/Academy Award Nominee Mary J. Bilge. Ronsale also enlists in the Army and, for the first time, goes to a continent where he is not judged primarily for his skin color. Ronsale and Jamie both experience the horrors of war (we see brief glimpses) but also the love — both emotional and physical — of the grateful liberated populace.

Returning Home

And then the war is over and both men come back to Mississippi and their “mudbound” existence. Jamie clearly has PTSD (not that it was called that after WWII) and alcohol is his preferred medication. Ronsale must deal with once again being a second-class citizen unable to walk in the front door of local general store. He reminisces, “I was a liberator. People lined up in the streets waiting for us. Throwing flowers and cheering. And here I’m just another nigger pushing a plow.” Ronsale’s father and mother warn him that his flashes of rebellious independence will not be tolerated by the racists around them, and it is not. Henry becomes more and more absorbed with keeping his “land” to the neglect of all else. (His brother says Henry is defined by his frequent statement “We will. We have to.” — “That was my brother, Henry. Absolutely certain whatever he wanted to happen would.”)

Jamie, who attempts to help his stubborn brother with his struggling farm, is unable to deal with his psychic injuries and his alcoholism. Laura tries to love someone who is preoccupied by keeping the deed to his land. She suffers the disaffection of a preoccupied spouse and the hard, dirty boredom of a poor farm wife. She laments, “Violence is part and parcel of country life. You’re forever being assailed by dead things. Dead mice, dead rabbits, dead possums. You find them in the yard. You smell them rottin’ under the house. And then there are the creatures you kill for food. Chickens, hogs, deer, frogs, squirrels. Pluck, skin, disembowel, debone, fry. Eat, start again, kill. I learned how to stitch up a bleeding wound… load and fire a shotgun… reach into the womb of a heavin’ sow to deliver a breeched piglet. My hands did these things… but I was never easy in my mind.”

The second half of Mudbound has numerous interwoven subplots involving these characters, all of which unfailingly hold one’s attention. Jamie and Ronsale form an unexpected (and forbidden) bond from their shared experiences. Pappy McAllen (Jamie and Henry’s father played to villainous perfection by Jonathan Banks — notorious for his portrayal of Mike Ehrmantraut in Breaking Bad) becomes enraged at their friendship. (Speaking to Ronsale, he hisses “I don’t know what they let you do over there, but you’re in Mississippi now, nigger. You use the back door.”) Henry becomes increasingly distant from Laura and she, inevitably, finds a developing attraction between Jamie and herself. The brutality and ugliness of the blatant racism of the Jim Crow era is powerfully portrayed with the KKK making a vicious appearance.

The second half of Mudbound has numerous interwoven subplots involving these characters, all of which unfailingly hold one’s attention. Jamie and Ronsale form an unexpected (and forbidden) bond from their shared experiences. Pappy McAllen (Jamie and Henry’s father played to villainous perfection by Jonathan Banks — notorious for his portrayal of Mike Ehrmantraut in Breaking Bad) becomes enraged at their friendship. (Speaking to Ronsale, he hisses “I don’t know what they let you do over there, but you’re in Mississippi now, nigger. You use the back door.”) Henry becomes increasingly distant from Laura and she, inevitably, finds a developing attraction between Jamie and herself. The brutality and ugliness of the blatant racism of the Jim Crow era is powerfully portrayed with the KKK making a vicious appearance.

Superior Writing, Cinematography, and Acting

Based on Hillary Jordan’s award-winning, 2008 debut novel by the same title, the film was directed and co-adapted for the screenplay by Dee Rees, who made waves in indie films with her previous directorial efforts for Pariah (2011) and Bessie (2015). The film maintains the structure of the book where each chapter is told through the POV of a different character (thereby the numerous voice-overs). The indie film was shown at Sundance in 2017 with resulting standing ovations (yes, the film does have that type of ending — as opposed to the novel). Netflix snapped it up, making it available to a much wider audience.

The vistas of farmland and scrabble-poor farms (filmed not in Mississippi but Louisiana) set an indelible mood upon the viewer. Rachel Morrison’s cinematography (I wondered why this film reminded me of the under-appreciated Fruitvale Station) is exceptional, earning her the first Academy Award nomination to ever go to a female. Morrison admits she would have liked to shoot on film but the filmmakers could not afford it. Still, the muted richness of her cinematography, “inspired by Gordon Parks’ celebrated color photography in Life magazine”* is haunting.

I am not as blown away by Mary J. Blige’s acting as some are but it is interesting to see her without makeup, false eyelashes, and highlighted hair. And her Academy Award nominated song “Mighty River” is memorable (as long as you do not look too closely at the lyrics). The actors who, in my opinion, stole the show were Mulligan/Laura with her sad, fated, and faded portrayal and Mitchell/Ronsale who so visibly struggles with his role in life and what to make of it.

One can see evidence of the limited budget. For instance, unlike Dunkirk (an impossible comparison) and many other more modest films, the war scenes were narrow in scope with, most notably, shots of Jamie’s bomber only showing a cockpit view of action above the plane rather than having the camera pull back to show the entire scene. Many fairly obvious short cuts were also made in action scenes showing results of events rather than the event itself. However this film is not an action film, but rather one that concentrates on character, emotion, motivation, and mood.

One can see evidence of the limited budget. For instance, unlike Dunkirk (an impossible comparison) and many other more modest films, the war scenes were narrow in scope with, most notably, shots of Jamie’s bomber only showing a cockpit view of action above the plane rather than having the camera pull back to show the entire scene. Many fairly obvious short cuts were also made in action scenes showing results of events rather than the event itself. However this film is not an action film, but rather one that concentrates on character, emotion, motivation, and mood.

Regardless, I enjoyed the development of the different characters. Some change for the better, and some do not. You ponder how different their lives could have turned out in a more just milieu. And you speculate where their lives would go from the film ending (the novel gives hints). You are left, once again, saddened by how slowly things have changed in the last 70 years (my lifespan). Two feet forward and one foot slipping back into the mud.

In Need of Grace

As Hap Jackson says in his accusatory eulogy towards the end of the film, life can be bleak. (In the film he recites the following in KJV which makes it difficult to follow — I prefer the more easily understood “Message” version):

Job 14:1-17 (selected) We’re all adrift in the same boat:

too few days, too many troubles.

We spring up like wildflowers in the desert and then wilt,

transient as the shadow of a cloud.

Do you occupy your time with such fragile wisps?

Why even bother hauling me into court?

There’s nothing much to us to start with;

how do you expect us to amount to anything?…

For a tree there is always hope.

Chop it down and it still has a chance —

its roots can put out fresh sprouts.

Even if its roots are old and gnarled,

its stump long dormant,

At the first whiff of water it comes to life,

buds and grows like a sapling.

But men and women? They die and stay dead.

They breathe their last, and that’s it.

Like lakes and rivers that have dried up,

parched reminders of what once was,

So mortals lie down and never get up,

never wake up again — never.

At the end of this film a Christian is asked to do something not many of us would (in dwelling on it I do not think I could on my best day). Will he forgive a person with an act of unwarranted (isn’t it always?) grace? The last few dramatic scenes complete what we viewed at the start of the film (with little initial understanding then, but “now we know”). While this story is fiction I am certain that in all the years of reconstruction and Jim Crow there were similar instances where pride was melted away in Christian “turn the other cheek” mode and, undeserved, grace was dispensed.

So see this film for the complex story lines, the wonderful cinematography, and the memorable acting. See it for a reminder of how far we’ve come and how easily we’ve slipped back. See it for that moment of grace and, perhaps, the beginning of forgiveness. If you are subscribed to Netflix you really have no excuse not to.

__________________________________________

*http://www.indiewire.com/2018/01/mudbound-cinematography-rachel-morrison-oscar-history-1201916935/