We know the story. Priests in the Catholic church abused lots of kids for a long time. With a story so familiar is it worth seeing Spotlight? Absolutely. Spotlight allows the viewer to re-enter the ignorance of the reporters who said that a priest wouldn’t do this, or if a couple priests were guilty then surely they were isolated cases. Both hopes are sadly shown to be false. We in 2015 know this; it’s recent history. Spotlight allows us to journey with the reporters as they witness the embodied pain of the victims and slowly shed their doubts as the horror of the scope, studied choice of vulnerable victims, and intentional subterfuge creeps upon them from all sides.

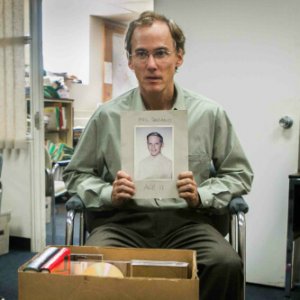

One of the earliest breaks comes from Phil Saviano, a victim who formed a support group for other survivors of priest abuse. Frustrated with the doubt of the reporters, he vents, “They say it’s just physical abuse, but it’s more than that. This was spiritual abuse. You know why I went along with everything? Because priests are supposed to be the good guys.”

Kevin M. Burke, a district attorney working on the case, tells the Globe that, “… what really struck me, in communications with the Archdiocese, was that there was never any concern shown for the victims. Not the slightest nod of concern for these young people whose lives were turned upside down by this abuse.” Herein lies the basic failure of this scandal, a denial of the Gospel, siding with perpetrators against their victims, a failure of love.

“It Takes a Village to Raise Them. It Takes a Village to Abuse Them”

As these nominal Catholics uncover the scandal they are furious, completely unable to understand how this could have happened for so long and in so many cases with no real consequences.

Priests targeted vulnerable children from low income neighborhoods, often with single parent households, kids who weren’t watched as closely, who wouldn’t make much of a fuss. The problem wasn’t that these priests weren’t caught; they were. The problem was that they weren’t exposed. Parishioners received false reasons for their departure. Sometimes priests were sent to rehab facilities, but eventually, inexplicably, they were put back into rotation without the new or old congregation ever learning of their crime. Even as I write this I feel my face getting red, my stomach knotting – anger and outrage are reasonable outworkings of the truth of these heinous crimes.

However, while anger is understandable it often frames the situation as something like “How dare these evil men do such evil things.” The dichotomy of good and evil, black and white, is unchallenged, the lines are just moved. Previously priests had been in the good category, maybe out of touch, certainly not guilty of molestation. As the film progresses we see the reporters increasingly putting priests and the whole Catholic church in the “evil” category while they, the truth revealers, remain the “good guys”.

However, while anger is understandable it often frames the situation as something like “How dare these evil men do such evil things.” The dichotomy of good and evil, black and white, is unchallenged, the lines are just moved. Previously priests had been in the good category, maybe out of touch, certainly not guilty of molestation. As the film progresses we see the reporters increasingly putting priests and the whole Catholic church in the “evil” category while they, the truth revealers, remain the “good guys”.

By the end of the movie, with pressure to keep the story under wraps coming at the reporters from all sides, they momentarily believe that maybe everyone knew about this story except them. This belief can only be maintained for so long as it slowly dawns upon the point man, Robby Robinson, that they all knew. Everyone knew something was wrong, even the Spotlight team. Blame shifting is ultimately another form of falsehood. Everyone is to blame. As Mitchel Garbedian, the lawyer for scores of abused victims says, “It takes a village to raise them. It takes a village to abuse them. That’s the truth of it.”

This insight was more profound for me than all the others. Greater than the revulsion at church leaders targeting kids, greater than the list that seemed to never end of priests and parishes involved, watching these reporters realize they knew all along and were just as culpable was worth the watch. Because really, how is our life different? Name the issue: racism, systematic poverty, militarism, homophobia, we often see the world in black and white, with us in the light and our enemies in the dark. In these moments, we too are understandably but sorely confused. We all have someone else’s blood on our hands.

“I Know I Won’t”

Living in the post-scandal world we are not only familiar with the problem but also with the outcome: mass exodus. Again, Kevin Burke says it succinctly, “The church’s leaders should be worried about a lot of things, but they should be most afraid of the lack of deference now shown them…They should not think that once this scandal fades, people will come running back to them. I know I won’t.” Unfortunately, he’s not alone. Not only did the sin and silence of Catholic clergy directly affect the family abused, they indirectly affected the attitude current generations and generations to come have toward God.

Even before the story broke this dynamic was playing out among the team of reporters. Mike Renzedes, played by Mark Ruffalo, always believed he’d go back to the Catholic church once he was older and settled down. Hearing the testimony of victims makes that seemingly impossible. Sacha Pfeiffer, played by Rachel McAdams, was actually attending mass with her grandmother before the story. Halfway through the movie she can’t stand to look at the priest anymore.

Even before the story broke this dynamic was playing out among the team of reporters. Mike Renzedes, played by Mark Ruffalo, always believed he’d go back to the Catholic church once he was older and settled down. Hearing the testimony of victims makes that seemingly impossible. Sacha Pfeiffer, played by Rachel McAdams, was actually attending mass with her grandmother before the story. Halfway through the movie she can’t stand to look at the priest anymore.

Their true loyalties had already been shifting for some time. What they uncover gives that shift almost a moral imperative. To stand with the church is to stand with abusers.

Obviously this is a huge problem. Not simply that people are leaving the church or that people may see the church as a haven for criminals. But that God himself becomes identified with priests and bishops who are morally corrupt, who should be opposed on every level, who targeted and harmed vulnerable children and then held up the host as if nothing was wrong.

One of my local pastors recently remarked that white people who don’t set out to undermine their social privilege can’t help but be racist. After watching this movie I want to amend that statement to focus on Christians. In light of these tragedies, those of us who don’t set out to undermine belief in a God who isn’t morally outraged when his vulnerable children are targeted aren’t in proper relation to that God. Spotlight could be seen as anti-church. I don’t think so, I think Spotlight is a gift, a call to remember our history, and act accordingly.