J’Ai Perdu Mon Corps (I Lost My Body) played during the Milwaukee Film Festival in 2019. I only got to a couple films this year, but it’s always a joy to attend. I Lost My Body will be streaming on Netflix in November, 2019.

– – – –

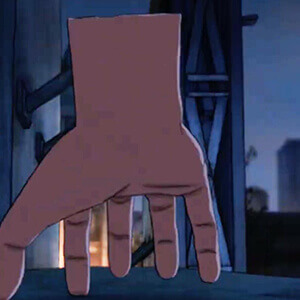

One of the weirdest additions to the Addams Family 1960s TV series was Thing, a disembodied hand. Often appearing in a box on a table, Thing would perform simple tasks for the family like turning lights off, changing the channel, ringing a bell, snapping. In the 90s movie versions Thing was independently mobile, skittering around on its fingers like a pale, fleshy spider. Until there’s a gritty Thing origin story, this French film about a hand searching for its body is an excellent substitute. A sometimes profound meditation on memory, fate and meaning, I Lost My Body explores universal themes through a beautifully animated, sometimes macabre, magical realist lens. Now let’s try and get through this without any unintentional ‘hand’ puns.

In the Shadows in the City of Light

Naofel, a lonely, distracted, young man living in Paris, questions the meaning of his life after a series of tragic accidents. A quiet film about fate takes a turn toward the surreal when the main perspective turns out to be, not Naofel’s directly, but that of his recently disembodied hand. Finding itself in a hospital refrigerator, Hand sets off on an incredible journey to reunite with its body.

The story unfolds outside of time as Hand remembers its life attached to Naofel. We bounce from past memory to past memory, sensation to sensation, all the while creeping inexorably to the moment of severance. As the gaps of Naofel’s tragic life fill in, the present unfolds from Hand’s point of view. Attacked by hungry rats in the subway, playing with a sleepy baby, crossing eight lanes of traffic on an umbrella — Hand’s adventure to find its body is strange, scary and somehow poignant.

Naofel’s life is an aimless mess until a chance meeting with Gabrielle, a local librarian, instills in him a sense of purpose and direction. He pursues her in his own, weird way (it looks more like stalking at first). He re-introduces himself to her under false pretenses and, as the two develop a close friendship, creates an idealized version of himself that is cut off from his painful past. As they grow closer and he grows more confident in his future, Naofel starts to ask questions about fate and free will. Has he been fated to be here, with Gabrielle? Through a series of flashbacks it certainly seems like his random tragedies have led him to this point.

The key conversation in the film finds Naofel scheming openly about defying fate. His plan is to do something random, something completely unexpected, something absurd to throw fate off his scent. As Hand desperately dreams of reconnecting, Naofel struggles to understand his past without succumbing to despair.

It’s always a treat to see hand-drawn animation on the big screen, and it’s a delicate balance to combine it with computer-generated art. Too much computer work and it’s a jarring disconnect that pulls you out of the story. I Lost My Body blends the two media perfectly. The style is fluid and realistic without being overly fussy; the flat colors and subdued palette compliment the emotional weight and pacing. Experiencing the city from the height of a steepled adult hand reveals a whole new world of details and odd perspectives.

Where Would the Body Be?

I can’t help but think about the “body” metaphor found in the New Testament. In a rhetorical flair, Paul compares the new christians to parts of a body — hands, feet, eyes — and we all make up the whole. In our 21st century context it sounds almost trite “We get it, we’re a family of useful members who are stronger together than apart.” In a “melting pot” culture like America, this idea is baked in to our self-concept. Consider how it must have sounded in a highly stratified empire like ancient Rome: it must have been radical. Paul specifically mentions different ethnic groups (“Jews” and “Greeks”) and social classes (“slave” and “free”). These groups would have never mixed – not socially, not economically, not culturally. But now they are considered equal members of a whole?

I can’t help but think about the “body” metaphor found in the New Testament. In a rhetorical flair, Paul compares the new christians to parts of a body — hands, feet, eyes — and we all make up the whole. In our 21st century context it sounds almost trite “We get it, we’re a family of useful members who are stronger together than apart.” In a “melting pot” culture like America, this idea is baked in to our self-concept. Consider how it must have sounded in a highly stratified empire like ancient Rome: it must have been radical. Paul specifically mentions different ethnic groups (“Jews” and “Greeks”) and social classes (“slave” and “free”). These groups would have never mixed – not socially, not economically, not culturally. But now they are considered equal members of a whole?

“Now God has placed each member in the body just as he desired…The members of the body which seem to be weaker are necessary; and those members of the body which we consider to be less honorable, on these we bestow more abundant honor…that there may be no division in the body, but that the members may have equal care for one another.”

Imagine being a slave and being told you are “necessary” and “worthy of honor”! Imagine being an ethnic outsider and told you are chosen by God and equal with the ethnic insiders! A hand is more than just a discrete lump of flesh. In I Lost My Body the Hand remembers, feels and carries with it a longing to be reunited with the rest of the body. It’s of no use without all the pieces that connect it — the muscles, bones, tendons — and the body is incomplete without its hand.

Ultimately I Lost My Body is a story about finding a path past trauma. It’s an excellent animated fairy tale that leaves the viewer with a sense of loss and recovery at the same time. Stream it on a big screen to experience the beautiful animation as largely as possible.