Despite the billing it has received, Hereditary is not primarily a horror film. Yes, it continues A24’s unsettling run of hybrid horror successes, along with The Witch and It Comes At Night. And yes, it is the scariest, most unsettling movie to hit theaters in years. But at the heart of Hereditary’s blackened soul lies a tortured family drama.

For a film so imbued with subtlety, it feels almost sacrilege to write about Hereditary in such blunt terms. Ari Aster’s debut feature is equal parts nightmare-inducing and core-shattering, a film so steeped in haunting imagery, it’s easy to miss the very real psychological toll it’s taking on the viewer. But to say too much is to neuter the film of its power, a mistake I won’t make here.

So then how do we discuss a piece of art that holds its secrets so tightly, only to unveil them in a slow, menacing fashion, cranking up the dread dial as it goes? We might as well start with the very heart just mentioned in the beginning: family drama — maybe, more appropriately, family trauma — and the ways it can be passed down quietly throughout generations.

“She Isn’t Gone”

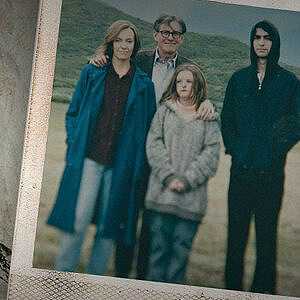

From its outset, Hereditary is interested in providing us intimate, if untelling, views of the Graham family. Visitations, family dinner, bedtime, workshops… each is a window into the soul of both the family members and their differing dynamics. And for much of the first and second acts, each space and interaction is haunted by the mysterious spectre of the family matriarch: Grandma Ellen.

Nothing about Ellen’s death can be seen as necessarily tragic, especially not from the perspective of 50 percent of the Graham family. We do, however, see a sort of longing from the youngest daughter, Charlie. She seems to mourn in her own special, almost understanding, way. She even appears to see well ahead of her family members, at one point asking her mother, “Who will take care of me… when you die?”

Charlie isn’t the only one affected by her grandmother’s unknowable legacy, juxtaposed by Annie as “warm” and “inviting” as well as “private” and “harsh” at her visitation. Annie, uninterested in further inhibiting her family with grief, seeks comfort at group therapy, mourning the time she lost with her mother as well as the times after she let her back in. She seems especially concerned for her children, the first of which (Peter) was held back from their grandmother while the second (Charlie) was — and yes this is a quote — “given.”

Charlie isn’t the only one affected by her grandmother’s unknowable legacy, juxtaposed by Annie as “warm” and “inviting” as well as “private” and “harsh” at her visitation. Annie, uninterested in further inhibiting her family with grief, seeks comfort at group therapy, mourning the time she lost with her mother as well as the times after she let her back in. She seems especially concerned for her children, the first of which (Peter) was held back from their grandmother while the second (Charlie) was — and yes this is a quote — “given.”

Even Peter and Steve, who are both seemingly unaffected by Ellen’s death, are thrown by the way it seems to unsettle the women in their home. As the film progresses — and the tragedies pile up — this idea develops further. The sometimes years-old choices that Ellen and Annie make unravel, and we’re shown the ways they physically and emotionally torment the Graham family, creating wedges that bury themselves into flesh, dividing both soul and spirit and joint marrow. It’s a biblical double-edged sword with wicked intentions, a Satanic butterfly effect that continues its evil flight path to the grisly, gory end.

“It’s Heartening to See So Many Strange, New Faces”

For a film so instantly celebrated and so accomplished in vision, it’s shocking how little star power is behind it. Much of the recognizable talent thrives on screen. Gabriel Byrne is incredibly accomplished and brings the same sort of assured confidence to his role as Steve Graham. And Alex Wolff (Patriots Day, Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle) is haunting as the awestruck Peter, an unknowing firstborn who wears his scars above and below the surface, a cornucopia performance overflowing with hurt.

However, it’s the women of Hereditary that bring an extra shot of terror to this toxic cocktail. Newcomer Milly Shapiro plays Charlie with an innocent strain of creepiness, a teenager you or I might have known in our younger lives. She keeps to herself and draws incessantly, but her desire for chocolate rivals that of any non-fiction boy or girl. There’s something abnormal about her… or is there? That’s the tightrope Shapiro walks to heart-rending effect.

And if Shapiro is the valuable new commodity, Toni Collette is the priceless, charred gem at the heart of the crumbling house. Collette brings a new meaning to “tortured” in her leading performance, combining wrenching anguish with a sort of rejected victimhood that so effectively communicates her position. As a mother unable to protect her family from those inside and outside the home, her fingernails dig and dig and dig until they draw blood; both hers and ours.

To greatest effect, though, is the work we see from the host of behind-the-scenes artists. Writer-director Ari Aster succeeds as a master of tone in his debut feature. The film is lavishly excessive in both audio and visual horror, pulpy to the point of nauseating while retaining its resonance. However, Aster doesn’t reveal his hand too quickly, mastering the art of restraint until the game has been had. The last 30 minutes is a boulder barrelling uncontrollably down the hill, the only unknown being when and where it will end up.

To greatest effect, though, is the work we see from the host of behind-the-scenes artists. Writer-director Ari Aster succeeds as a master of tone in his debut feature. The film is lavishly excessive in both audio and visual horror, pulpy to the point of nauseating while retaining its resonance. However, Aster doesn’t reveal his hand too quickly, mastering the art of restraint until the game has been had. The last 30 minutes is a boulder barrelling uncontrollably down the hill, the only unknown being when and where it will end up.

Also of note are composer Collin Stetson and editors Jennifer Lame (Frances Ha, Manchester By the Sea) and Lucian Johnston. Lame and Johnston do especially good work in several of the most harrowing scenes, allowing us to sit in the unflinching, blood-soaked consequences of the Graham family’s past until we can’t bear to see anymore; I mean this literally, as I once looked away at one particularly gruesome moment that seemed to drag on for ages. It’s all backed by Stetson’s daunting nightmare soundtrack. While themes are typically used in film scores to introduce elements of reliability, Stetson’s music refuses to make us feel comfortable, allowing us to take each turn with the sort of unfamiliarity that accompanies the Graham family through much of the narrative.

In the hands of Aster and his peers, Hereditary feels very sure of itself while never allowing us to glimpse around the corner, only taking us as far as we dare go before thrusting us into the gaze of the new horrors that await.

“The Sacrifices We Made Will Have Been Worth It”

The only moment of Hereditary where I was transported out of the film and back into the real world was, unfortunately, the final scene. In the film’s resolving last few minutes, there’s a sharp thematic turn Aster finally shows us the final product of his story’s horrific means. And it all feels so… diminutive.

I won’t spoil anything about how Hereditary ends. So much of what makes it great is the lack of knowledge the viewer takes into it. But I couldn’t help but feel amused by how small everything ended up feeling. The central narrative’s resolving moments seem almost comic in the face of the upsetting two hours that preceded it, shrinking what would be an otherwise brutal fable on family ties into a lesser, more campy version of itself. It’s an ending that doesn’t feel up to snuff with its dynamic, complex story. Instead, it feels unresolved. It almost would have been more effective to cut the whole thing entirely, leaving the broken shards Aster’s mind hath wrought.

But I also think there’s an element to Hereditary, hard to shake as it is, that would remain unresolved regardless of how the film ended. What we’re left wanting for this ailing, broken family is healing: healing from pain, healing from abuse, or just healing from death and disease. It’s a remedy that is sought in different ways throughout the film, be they escapism or therapy or exploration. Still, the trauma remains, clenched tightly in Annie’s fists until it bursts forth, consuming everyone around her.

But I also think there’s an element to Hereditary, hard to shake as it is, that would remain unresolved regardless of how the film ended. What we’re left wanting for this ailing, broken family is healing: healing from pain, healing from abuse, or just healing from death and disease. It’s a remedy that is sought in different ways throughout the film, be they escapism or therapy or exploration. Still, the trauma remains, clenched tightly in Annie’s fists until it bursts forth, consuming everyone around her.

That this bruising portrait of the damage we do to those we love never finds its consummate healer leaves us, in the end, in a deep funk. It’s something I’ve felt since I quickly shuffled out of the theater, and something I had a hard time shaking.

And then I remembered the best solution to this type of trauma is, ultimately, in letting it go. Not unresolved, but to someone more capable of resolution than we are. That Annie and the Graham family are never able to release themselves from the burdens of the past is a deep sorrow worth pondering.

But Hereditary’s core mission isn’t to show us the ways we’re capable of being our own saviors. It’s to show us the many ways we aren’t, the ways those efforts will ultimately go rotten, leaving us with the shells of our former selves: incomplete and hopelessly broken.