“Showing off,” writes Steve Martin in L.A. Story, “is the idiot’s version of being interesting.” The Last of Sheila is populated with L.A. idiots who show off, show people in fact, who don’t know how to just show up, to be present, to be personal.

They are smart — or at least they are smart asses — and a few of them are even genuinely intelligent — but they’ve been striking deals and saying lines and hitting marks for so long, they’ve forgotten how to think and to feel; they’ve mistaken people for rocks they can grasp and step on as they climb to the top. And, as Bette Davis remarks in another film that was bitchy long before this one, “the things you drop on your way up…you forget you’ll need them again.”

The Same B Group

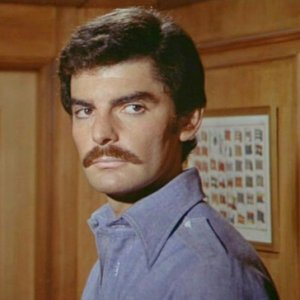

Who are these show people? A writer, Tom (Richard Benjamin), an agent, Christine (Dyan Cannon), an heiress, Lee (Joan Hackett), a director, Philip (James Mason), a manager, Anthony (Ian McShane) and an actress, Alice (Raquel Welch). When each receives an invitation to a party thrown by influential producer Clinton (James Coburn), they accept, for reasons political instead of relational; these “six hungry failures” could use a break. Clinton’s going to break them, all right. And the eponymous Sheila? She’s not on the guest list.

“It’s the same B group that was at your house the night Sheila got bounced through the hedges,” Christine says, with characteristic sensitivity, to Clinton. Sheila, we gather, was Clinton’s girlfriend, a prostitute who became a gossip columnist but perhaps should have become a model for hair product commercials. None of that seems to justify the hit-and-run that ended her life and opens the film.

“It’s the same B group that was at your house the night Sheila got bounced through the hedges,” Christine says, with characteristic sensitivity, to Clinton. Sheila, we gather, was Clinton’s girlfriend, a prostitute who became a gossip columnist but perhaps should have become a model for hair product commercials. None of that seems to justify the hit-and-run that ended her life and opens the film.

Whodunit? That’s why Clinton is getting this party started, a year after the killing. But there won’t be police, or a detective. Clinton is a “minor league sadist” and socially acceptable sociopath who has planned the “Sheila Green memorial gossip game” in which everyone is a player. Each person has been given a card with “pretend gossip” on it — “You are an alcoholic” reads one. “You are a homosexual” reads another. It’s not pretend, though, as everyone will soon realize. The secrets are real. But everyone has someone else’s secret. “That’s the thing about secrets,” Alice muses. “We all know stuff about each other, we just don’t know the same stuff.”

Events for Friends

As closeted gay men, co-writers Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins knew stuff about each other. “Before they were co-writers, Sondheim and Perkins staged elaborate, immersive events for friends,” writes Rosemarie Keenan in a magnificent essay on Sheila. “In one treasure hunt larded with complex clues, four teams rode around New York City in limousines…at one stop on the journey an older white-haired woman (Perkins’s mother) served chocolate cake to her visitors. When team members put the slices back together the clue to their next destination was written in the frosting…Herbert Ross’ team won. Appreciating the showmanship involved, Ross suggested Sondheim write a murder mystery for him to direct.” Apparently Ross also “convinced Warner Brothers to commission Sondheim to write a screenplay in which both the audience and the characters could play along…Sondheim eventually invited Perkins to collaborate on the script.”*

If the above history doesn’t fill your heart like a balloon about to burst,** you’re probably not a fan of musicals, or a gay man, and no, those are not synonymous. Sondheim has written the only musicals I love; Perkins starred in Psycho and my first e-mail address was normanbates2284@yahoo.com; Ross directed one of my favorite comedies from the ‘70s, California Suite. They all are responsible for stories in which I have found myself. Or rather who I want to be? Sometimes others are better at finding us. The others we call friends.

Social Solidarity

“The harder you try to keep a secret in, the more it wants to get out.” The irony is I can’t tell you which character says that, but the timing is cruel, yet understandable, and the character at which it is directed, Lee, cries. She is the only character who cries, and, not coincidentally, the only Hollywood outsider of the group. Joan Hackett, an unheralded revelation of an actor, plays Lee, as with all of her characters, like beautiful papier-mâché in varying forms of production — soft and pliable, hardened and crisp, painted and impermeable. You get the impression that Lee really would lay down her life for a certain friend; then that friend would play it as she lays.

“There are gigantic themes here,” Philip announces near the end, “worthy of Dostoevsky: innocence, guilt, hatred, loyalty — ” and community. In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky writes, “All mankind in our age have split up into units; they all keep apart, each in his own groove; each one holds aloof, hides himself and hides what he has, from the rest, and he ends by being repelled by others and repelling them…he has trained himself not to believe in the help of others, in people and in humanity, and only trembles for fear he should lose his money and the privileges he was won for himself…the true security is to be found in social solidarity rather than in isolated individual effort.”

“There are gigantic themes here,” Philip announces near the end, “worthy of Dostoevsky: innocence, guilt, hatred, loyalty — ” and community. In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky writes, “All mankind in our age have split up into units; they all keep apart, each in his own groove; each one holds aloof, hides himself and hides what he has, from the rest, and he ends by being repelled by others and repelling them…he has trained himself not to believe in the help of others, in people and in humanity, and only trembles for fear he should lose his money and the privileges he was won for himself…the true security is to be found in social solidarity rather than in isolated individual effort.”

For the characters in Sheila, there is no social solidarity, only social climbing. The tragedy is not the secrets themselves, but that no one can share them apart from force. It’s all fun and games until you’re all alone. As the song over the credits says, “you gotta have friends.”

__________________________________________

*From Stephen Sondheim: A Casebook, edited by Joanne Gordon.

**Thanks, Alan Ball.