Most people living today have only a vague memory of the Vietnam War, or none at all. As a teenager growing up in a very conservative area my memories were taken from Walter Cronkite’s TV reports, my local paper, and a few radio broadcasts. We were told America was sending soldiers to Southeast Asia to prevent communism from taking over the continent (the “Domino Effect”) and that those communists were barbaric atheists. Until I went to Purdue University (about as conservative a secular college as you could attend but even there anti-government viewpoints were voiced) it never occurred to me that there might be another story to be told. My biggest worry was what my draft lottery number was going to be (it was very high), along with the well-being of my classmates who were being sent around the world. Some did not come back. But almost all of us thought the soldiers were giving up their lives for a “noble and good” cause.

Looking back 50 years while seeing documentaries like Ken Burns’ and Lynn Novick’s wonderful The Vietnam War makes me realize how censored the news was that we were receiving. In one of many instances, the bombing campaigns on Cambodia (and Laos) were never revealed to the American public until long after they occurred. Decisions about thousands of young Americans who would die in a futile, unwinnable war were made by a few men in power who were concerned with their pride and electability. And their decisions also contributed to the total disruption, and often the deaths, of the lives of hundreds of thousands of Asians — not just Vietnamese but Laotians and Cambodians. The actions in Vietnam also had the unintended result of sparking the genocide of a quarter of Cambodia’s population by Pol Pot’s ruthless Khmer Rouge.

A Young Girl’s Life

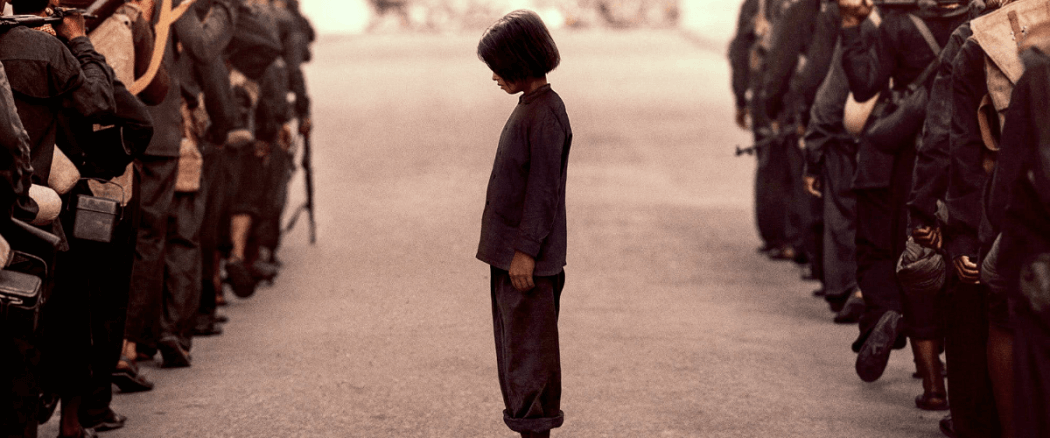

One of the people who lost nearly everything was a tomboyish Cambodian girl of five (at the film’s beginning), Loung Ung. Living in Phnom Penh in 1975 with her relatively well-to-do family including her parents and seven siblings, and with her father being a moderately high level official in the government, she experienced life not unlike a middle-class American contemporary. But when the government collapsed, the Khmer Rouge, communist rebels who had fought for many years against the present government (and covert American troops) came marching victorious but unsmiling into her city and life would never be the same for Loung and her family. Her father warned them to not speak of his job with the government. Fear permeated the older members of the family. Loung, at five years of age, had a limited understanding of what was happening.

Loung’s family was soon told, as were the millions who lived in Phnom Penh, that they must evacuate the city with only what they could carry but that they would be allowed to come back in three days. As her father suspected, that was a lie… one of many they would be told by the Khmer Rouge. As Loung’s family of nine marches further and further into the jungle (with millions of other evacuees) they had more and more of their possessions stripped from them. To Loung’s puzzlement, Buddhist monks are mercilessly persecuted, mocked as being “good for nothing” and “parasites.” Anything decorative or bright was confiscated — difficult for the mind of such a young child to comprehend. The family briefly stayed in the rural home of their mother’s sister but her aunt’s husband, in one of the film’s many heartbreaking scenes, tells them they must leave because if the communist troupes found out Loung’s father was a government official they would all be imprisoned or killed.

Loung’s family was soon told, as were the millions who lived in Phnom Penh, that they must evacuate the city with only what they could carry but that they would be allowed to come back in three days. As her father suspected, that was a lie… one of many they would be told by the Khmer Rouge. As Loung’s family of nine marches further and further into the jungle (with millions of other evacuees) they had more and more of their possessions stripped from them. To Loung’s puzzlement, Buddhist monks are mercilessly persecuted, mocked as being “good for nothing” and “parasites.” Anything decorative or bright was confiscated — difficult for the mind of such a young child to comprehend. The family briefly stayed in the rural home of their mother’s sister but her aunt’s husband, in one of the film’s many heartbreaking scenes, tells them they must leave because if the communist troupes found out Loung’s father was a government official they would all be imprisoned or killed.

The Killing Fields

They arrived at a work camp in the “Killing Fields” and are told all their clothes must be dyed into a nondescript black or grey, so as to have no one rank above his neighbor in status or style. They wore the universal sign of the Khmer Rouge — the red gingham “krama scarf.” They attended daily indoctrination classes relentlessly intoning the agrarian socialism and nationalism of the Khmer Rouge. She was brainwashed by incessantly being told that “Angkar” (the communist party) would “take care of them” but that they must “renounce all personal possessions and property.” “Angkar is your savior and liberator.” “Angkar is your mother and father.” Because of her intelligence, Loung was eventually chosen to be trained as a child soldier and learned to plant the land mines, millions of which still take their toll even now.

The Khmer Rouge encouraged and rewarded turning in any acquaintances or family who were in any way not loyal to the goals of Angkar and as her father feared, in time soldiers with assault rifles (which are everywhere) come to the family’s hut and tell Loung’s father they need him to work on a special work project. He is aware of their lie and bravely tells each of his children goodbye and gives his wife a final embrace. He is then marched off into the jungle, there is a rifle shot, and startled bird flocks take flight. She never sees her father again.

The Khmer Rouge encouraged and rewarded turning in any acquaintances or family who were in any way not loyal to the goals of Angkar and as her father feared, in time soldiers with assault rifles (which are everywhere) come to the family’s hut and tell Loung’s father they need him to work on a special work project. He is aware of their lie and bravely tells each of his children goodbye and gives his wife a final embrace. He is then marched off into the jungle, there is a rifle shot, and startled bird flocks take flight. She never sees her father again.

As her siblings are relocated or join the fighting army, her dwindling family becomes more difficult to maintain. Her mother, despairing of Loung’s future, tells Loung, along with her youngest brother and slightly older sister, to run away into the jungle and when (or if) she is found she is to say that they are orphans. Loung is eventually all alone in a world gone mad. Her mother is now left alone and desolate.

Through the Eyes of a Child

Unlike previous movies about the Cambodian genocide (The Killing Fields starring Academy Award winner Haing S. Ngor being the most prominent) this movie is seen through the eyes of a 5 to 9 year old. It is based on the first of Loung Ung’s three book cycle (“First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers” followed by “Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left Behind” and “Lulu in the Sky: A Daughter of Cambodia Finds Love, Healing, and Double Happiness.”) Losing her childhood, separated from other family members, living in a merciless world filled with hate and genocide, how did she keep her sanity? And how did she survive to become a world renowned author and leader in the fight for human rights around the world?

A Truly Cambodian Film

The story of Loung’s rescue and eventual reunification with some of her family is fascinating. Despite its 136 min run time, there was no lull in my attention. The battle scenes when the Vietnamese fight the Khmer Rouge are tense and well-staged, while mostly, as in the work camp scenes, avoiding overt butchery. I am impressed by Angelina Jolie’s direction of hundreds, if not thousands, of actors in these scenes. It is a tribute that her film is Cambodia’s entry into the Best Foreign Film Category of the Academy Awards and is considered a favorite to be one of the finalists.

The actors in First They Killed My Father are all Cambodians unknown in this country with the majority being either survivors or children of survivors of the Cambodian genocide. Angelina Jolie (best known as a director up to now for the movie Unbroken) directs this film after pushing for the book’s translation to film. She had a special passion for the project since becoming a Cambodian citizen in 2005 in addition to adopting a Cambodian orphan in 2002. Jolie insisted the entire film not only use native Cambodians but that it have them speak their native Khmer. She wisely hired veteran cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, winner of the Academy Award for Slumdog Millionaire, and the film repeatedly has striking images. Most noticeable is the film being told at the level of 5-year-old Loung. The camera gazes up at adults, then turns to her wide-eyed puzzlement and wonder. There is shot after shot of Cambodian landscapes and beauty which dissolves into slave labor, starvation, and dead bodies.

The actors in First They Killed My Father are all Cambodians unknown in this country with the majority being either survivors or children of survivors of the Cambodian genocide. Angelina Jolie (best known as a director up to now for the movie Unbroken) directs this film after pushing for the book’s translation to film. She had a special passion for the project since becoming a Cambodian citizen in 2005 in addition to adopting a Cambodian orphan in 2002. Jolie insisted the entire film not only use native Cambodians but that it have them speak their native Khmer. She wisely hired veteran cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, winner of the Academy Award for Slumdog Millionaire, and the film repeatedly has striking images. Most noticeable is the film being told at the level of 5-year-old Loung. The camera gazes up at adults, then turns to her wide-eyed puzzlement and wonder. There is shot after shot of Cambodian landscapes and beauty which dissolves into slave labor, starvation, and dead bodies.

A Special Credit to Angelina Jolie

A special credit goes to Jolie. She is famous (and notorious) for several reasons and some are not admirable. But it is almost certain she was one of the few directors who could have gotten this movie made. Likewise and sadly, Netflix is in today’s cinema business world one of the few places that a movie like this (unknown actors, foreign language and subtitled, a little known event taking place in a small country and an unpleasant subject) could be made. Her insistence and persistence in bringing Loung’s memoir to the screen and her skill in telling the fascinating story from a unique perspective (a child’s) deserves special commendation.

It was a terrible era for Cambodia and this Netflix movie pulls no punches other than keeping the torture and executions off-screen. Almost 2 million people perished by either starvation or violence. Infants and children were given no more mercy than the adults and an entire generation was decimated. Almost all Buddhist monks were slaughtered, along with artists and intellectuals. Pol Pot’s reign will go down, along with Hitler’s, as one of the most ruthless and evil in modern history. This film looks at this genocide, largely ignored in this country despite our being one of its main causes, through the wide eyes of a child, telling that story with, in the end, hope and a witness to our power to survive the worst a broken world can make us suffer.