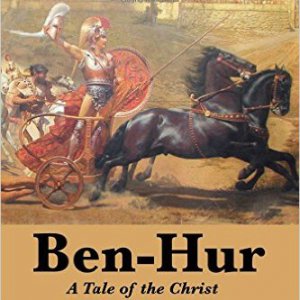

Few adults have not come across some version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The hugely popular book, written by Civil War General Lew Wallace, is said to be the first novel ever read by many of the millions of Americans who bought or borrowed the tome (450 pages or so) in the last 20 years of the 19th Century and beyond. Published in 1880 it probably sold more than a million copies over the next 30 years, an astounding number for that time. It was then translated to a successful and long-running stage play in the early 20th century (I am trying to imagine the sea battle and chariot race on stage) and then to multiple film versions, a TV mini-series (said to be awful) and even an obviously stripped down 77 minute animated version for children. It just won’t go away and this summer it was back for a fairly lavish redo which its producers hoped would rival the definitive 3 hour and 32 minute, 1959 William Wyler epic.

I will admit the story has a special place in my heart. When the 1959 film came out I was 12 years old and so very intensely jealous of my sister 4 years older than me who went to see it with her boyfriend. (My parents thought movies were a terrible waste of money and time — nearly a Ten Commandment type sin — but my sister’s dates were beyond their control.) I felt I was the most hapless person in the world in that I could not see it. As a consolation I bought an LP record of the soundtrack (in a deluxe boxed edition with a picture book — more like an 8 page flyer). If I remember correctly, I shelled out a hard obtained $4.98 for that LP that I played over and over. And of course I read Wallace’s book. But oh, to see it on the screen. Before the age of video, it would be years before I could. When I did, it did not disappoint.

The Novel/The Author

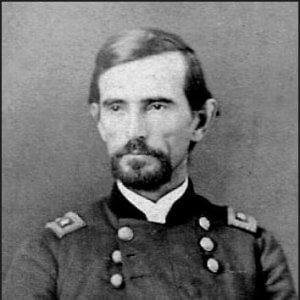

What a curious person the Crawfordsville, Indiana born Lew Wallace was. Coming from a notable but not wealthy family, he became an attorney like his father and crossed paths with Abraham Lincoln who lived just across the border in Illinois and was beginning to see his political fortunes rise. Joining the army in 1846 for the Mexican War, Wallace rose to the rank of general by the time of the Battle of Shiloh in 1862 in which he was (probably unfairly) blamed for the heavy Union losses. At that point he was mostly shuffled to the side for the rest of the Civil War. In the end Wallace’s military career was complicated with numerous controversies. But to most in the military, rightly or wrongly, he was considered to be “disgraced.”

A chance meeting on a sleeper car in 1876 with the renowned American speaker, veteran, author, and atheist Robert Ingersoll, the conversation for which lasted all night, caused Wallace to seriously question his Christian faith. He decided to write a novel of the time of Christ with confidence that during the course of writing it, his doubts would be answered one way or the other. Four years later the novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was completed with his unbelief resolved. The novel sold so well that Wallace lived the rest of his life in financial comfort and his notoriety would be forever preserved. How ironic that the nation’s greatest atheistic proponent of the time was causative for the writing of a book to rival the Bible as foundational to the belief of so many Christians of that time.

A chance meeting on a sleeper car in 1876 with the renowned American speaker, veteran, author, and atheist Robert Ingersoll, the conversation for which lasted all night, caused Wallace to seriously question his Christian faith. He decided to write a novel of the time of Christ with confidence that during the course of writing it, his doubts would be answered one way or the other. Four years later the novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was completed with his unbelief resolved. The novel sold so well that Wallace lived the rest of his life in financial comfort and his notoriety would be forever preserved. How ironic that the nation’s greatest atheistic proponent of the time was causative for the writing of a book to rival the Bible as foundational to the belief of so many Christians of that time.

Wallace’s Story

The General’s well-known tale begins with two young men in Jerusalem at the time of Christ. One, Judah Ben-Hur, is Jewish royalty and the other, Messala, is a Roman orphan taken in by the Ben-Hur family. They are more than friends — almost brothers — living in the Ben-Hur home with Judah’s widowed mother Miriam (for some reason named Naomi in the 2016 film) and his near-adult sister Tirzah. But Messala chooses to join the Roman army to seek his destiny, much to the sorrow of the entire Ben-Hur family — especially Tirzah who has quite fallen for him.

After two years Messala returns a hardened soldier having risen in the ranks to being just under the head of the Roman garrison which enforces Caesar’s will on Jerusalem. However Messala is viewed suspiciously by his superiors because of his Jewish-tainted upbringing and they clearly want him to prove his fidelity to Caesar. To that end, Messala asks Judah to give him the names of any Jews he knows that support the zealots who are trying to overthrow the Roman occupation. Judah tries to maintain his friendship with Messala but in the end follows his principles and refuses to become an informant. Their friendship dissolves. As a result of an accident (portrayed differently in the various films) the house of Ben-Hur is accused of treason and being in league with the zealots. Messala’s superiors allow him to decide who is punished and how severe the punishment should be. Knowing he is being watched by his commanders, Messala forgoes any mercy to his former “family” and metes out terrible punishments for Judah as well as Miriam and even Tirzah.

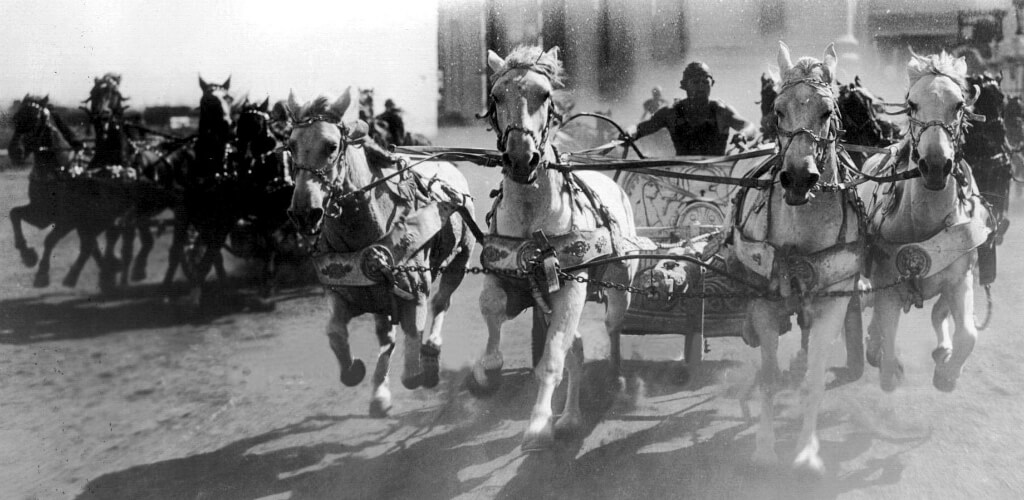

And thus begins the story of Judah Ben-Hur’s epic fight for survival. There are two center pieces of all the films. First, there is an amazing sea battle where Judah appears as a five-year galley slave (those unfortunate men who power the oars of Rome’s warships until they become weak and are thrown overboard). He participates in an elaborate battle when the Roman fleet is attacked by pirates but which ends in the ship Judah is on sinking. Secondly, the spectacular Roman Coliseum “Circus” where he duels with Messala in a “no-holds-barred, no law in the arena” chariot race. Four horse teams draw each of the chariots which come from across the Mediterranean civilization. The price for not finishing first is often death in the arena due to being thrown from one’s chariot or trampled by others. It was a “blood sport.”

And thus begins the story of Judah Ben-Hur’s epic fight for survival. There are two center pieces of all the films. First, there is an amazing sea battle where Judah appears as a five-year galley slave (those unfortunate men who power the oars of Rome’s warships until they become weak and are thrown overboard). He participates in an elaborate battle when the Roman fleet is attacked by pirates but which ends in the ship Judah is on sinking. Secondly, the spectacular Roman Coliseum “Circus” where he duels with Messala in a “no-holds-barred, no law in the arena” chariot race. Four horse teams draw each of the chariots which come from across the Mediterranean civilization. The price for not finishing first is often death in the arena due to being thrown from one’s chariot or trampled by others. It was a “blood sport.”

In addition, Christ Jesus is seen briefly interwoven between these events altering the course of Judah Ben-Hur’s life. In the end there is a miraculous (non-Biblical) miracle that occurs that affects Judah and his family like no other. Each film handles all of these events somewhat differently but all stick more or less to the same narrative. The novel itself covers much more ground going on at length after the chariot race and Christ’s crucifixion, which is the climax of the films. The remainder of the novel introduces and builds arguments for the idea of achieving prosperity through godliness and piety, which was a popular idea in the “gilded era” during which the novel was read, and was a forerunner of today’s prosperity gospel. Interestingly, the resurrection of Christ is not shown in any of the films.

Making the 1925 Film

After decades of steady sales of Wallace’s book (including overseas), and a 1907 silent “short” being made (which I have not seen but one questions the entire concept), the novel was transferred to stage where it was very successfully performed in various venues for 25 years until 1920. The Goldwyn Company (soon to become MGM) became interested in making a full length extravaganza and rights were obtained in 1922. The owner of the theatrical version, Mr. Abraham Erlanghar, was exceedingly shrewd and obtained amazing terms for the rights, including a clause giving him total approval of nearly every facet of the production and a very generous portion of any profit in addition to the large initial rights fee.

Like so many “big” Hollywood projects, the movie was troubled from the start. Initially shot in Rome where the unemployment of the upcoming Great Depression had already started to affect millions, many Italian extras were hired for the extravagant sea battle signing the required release that they could swim without any proof being provided. When a fire set on one of the ships got out of control and many extras had to jump into the ocean in their heavy armor, rumors flourished that a large number drowned. Allegedly the movie’s production manager took men to the area with chains to weigh down any bodies that might be floating on the surface. The facts of this incident were never known with certainty due to the poor records that were kept of the number and names of the Italian extras.

The movie continued to be plagued with innumerable delays and disasters. Almost all the leads for the film changed requiring extensive reshoots. The original director Charles Brabin was fired by studio boss Irving Thalberg and Fred Niblo was put in his place. By early 1925, the filming was completely bogged down due to replacement of leads as well as the director, general discontent by the crew, and finally a disastrous attempt at filming the chariot race in Italy. The surface of the track was not “suitable” for the horses and stuntmen which lead to numerous crashes and eventually the death of at least one driver.

MGM became increasingly concerned at the huge cost overruns and ballooning budget. Thalberg made the decision that the filming had to be shifted to Culver City, California if it were ever to be completed. The chariot race was restaged with a new “Circus Arena” constructed near what is now the intersection of LaCienega and Venice Boulevards (well within present city limits) in Los Angeles. Most historians agree that without Thalberg’s guiding hand the production would never have been brought to a conclusion.

MGM became increasingly concerned at the huge cost overruns and ballooning budget. Thalberg made the decision that the filming had to be shifted to Culver City, California if it were ever to be completed. The chariot race was restaged with a new “Circus Arena” constructed near what is now the intersection of LaCienega and Venice Boulevards (well within present city limits) in Los Angeles. Most historians agree that without Thalberg’s guiding hand the production would never have been brought to a conclusion.

The film ended up being the most expensive silent film ever made at $3.9 million due in large part to paying actors for sitting around while no footage was shot, the huge sets that needed to be constructed and then moved, and the film’s many technical difficulties. The sea battle used 48 cameras simultaneously, a record. The chariot race is said to be the most edited sequence ever shot on film, starting with 200,000 feet of film that was edited down to 750 feet, a ratio of 3.75 feet of film used for every 1000 feet shot.

Upon the resumption of filming in the spring of 1925, the film was completed by that fall (including the overwhelming editing required) and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ finally debuted late that same year. Audiences flocked to see it around the world. Still, it lost money for MGM due to the unfavorable terms of the initial contract with Mr. Erlanghar and its huge cost overruns. It was only on the re-release of the film in the early 30s (bucking the “talkies” which were taking over the market) that the film made any money for MGM at all.

An Epic to Set the Standard

It was quite an experience to see this silent film. I was able to see the Ted Turner restored version that was included in the “Fiftieth Anniversary Blu-ray Collector’s Edition” of the 1959 Ben-Hur released in 2009. As a special pleasure this restored version included the nine “two-color” or “two-strip” inserts (once thought lost) that were featured in the original film (but removed on its re-release due to continuing problems with “holding” the colors). The process was very new to that time (the first widely successful film to use the process was 1922’s The Toll of the Sea), but due to the difficulty and expense of making the Technicolor strips the process was not quickly adopted. In Ben-Hur the strips were put in for the parts of the film where Christ appeared and a few of the other prominent scenes (but not the sea battle or chariot race because of the high intensity lighting required by the Technicolor process). [See this short five minute video for an explanation of the process if you are interested https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8iy_MjegGWY.]

It is always hard for me to review a film from the silent era. The silent actors of the time made up for their inability to speak by exaggerated physical gestures and completely unnatural facial expressions. But given that, I was impressed by the emotion portrayed by Ramon Navarro as Judah Ben-Hur. (Navarro had quickly replaced the original choice of George Walsh in a role coveted but never offered to Rudolph Valentino.)

It is always hard for me to review a film from the silent era. The silent actors of the time made up for their inability to speak by exaggerated physical gestures and completely unnatural facial expressions. But given that, I was impressed by the emotion portrayed by Ramon Navarro as Judah Ben-Hur. (Navarro had quickly replaced the original choice of George Walsh in a role coveted but never offered to Rudolph Valentino.)

Messala was played by Francis X. Bushman who was quite famous in his time. He looks much older than the Messala of the other two movies (he was 43 compared to Navarro’s age of 26) and I did not care for his (over) acting. The roles of May McAvoy as Esther and the other women were all well-done. There were also prominent roles for Esther’s trusted father Simonides (a Ben-Hur financial manager and house slave who plays a much more central role in this film) and the Egyptian Queen Iras who is a “Mata Hari” for Messala — a role completely absent in the other films.

As for the production of the film, given the time and absence of green screen or CGI, the naval battle and, especially, the chariot race are truly amazing. William Wyler, the lauded, Academy Award winning director of the 1959 film, was actually an assistant director for the chariot race in this film and not surprisingly the scenes for the 1959 film are almost a duplicate of those in this film, albeit with much more camera movement and close-ups. The chariot race scene is said to be seminal in “introducing the modern concepts of film editing and montage to cinema” (per film critic Kevin Brownlow) and has been widely copied both in the 1959 production as well as numerous other films from 1998’s The Prince of Egypt to the pod race in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace. It certainly thrilled me and I marveled at the director’s ability to pull it off. However, there was an unscripted pile-up seen at the end of the race and several horses were put down as a result. In those days I suspect no one batted an eye.

The cast was truly one of thousands — said on posters to be more than 150,000 but a more truthful number was estimated at over 125,000 people. You can read in IMDB about the many (later-to-be-famous) actors who played extras in the film (just a sample: Clark Gable — where he met his future wife Carole Lombard for the first time, Myrna Loy, Mary Pickford, Joan Crawford, John Barrymore and Lionel Barrymore). In addition some of the extras included, surprisingly, “showgirls” who were given topless scenes (watch the extras in the scenes shot when Judah is in Rome). Despite the film being marketed as “The Picture Every Christian Ought to See” the for-that-time daring scenes were not deleted with the excuse given by the Board of Moral Standards that the film “depicted the beginning of Christianity.” (Huh?)

The cast was truly one of thousands — said on posters to be more than 150,000 but a more truthful number was estimated at over 125,000 people. You can read in IMDB about the many (later-to-be-famous) actors who played extras in the film (just a sample: Clark Gable — where he met his future wife Carole Lombard for the first time, Myrna Loy, Mary Pickford, Joan Crawford, John Barrymore and Lionel Barrymore). In addition some of the extras included, surprisingly, “showgirls” who were given topless scenes (watch the extras in the scenes shot when Judah is in Rome). Despite the film being marketed as “The Picture Every Christian Ought to See” the for-that-time daring scenes were not deleted with the excuse given by the Board of Moral Standards that the film “depicted the beginning of Christianity.” (Huh?)

Unlike the more recent remakes, the film’s title maintained the “A Tale of the Christ” suffix of the novel and was clearly marketed towards Christians, despite most of the financing coming from Jewish businessmen. The early scenes portrayed the story of the nativity with a Joseph who appeared to be old enough to be Mary’s grandfather, and Mary herself (Betty Bronson) as a beatific and almost motionless icon. Very odd for this day but apparently well liked in that time. The film also includes frank portrayals of Christ who is seen full-faced (as opposed to the 1959 film) but without dialogue. Much time and effort was spent on the opening nativity scene and the journey of the wise men. The “Star of the East” was done with special effects that were thought to be amazing for the time but seem pretty amateurish in this day. On the other hand the big “miracle” scene at the end is probably handled more believably, but less spectacularly, in this film than the others (do miracles have to be “believable”?). I would recommend you see it at least once if you are into film history and not put off by reading intertitles (which, by the way, are well done).

My rating (given the era it was produced) – A

The Making of the 1959 Film

William Wyler was given the task of remaking Ben-Hur and there probably was no better choice. Bringing an international stable of great film stars of the 50s together, the film was an epic by every definition (an epic is generally defined as a narrative on a grand scale, featuring a heroic — or more recently antiheroic — effort of an individual — or group of individuals — and taking place over a longer span of time). It has long been considered one of the best epics ever made (#2 on the AFI’s list of “The Best Movie Epics of All Time” behind only Lawrence of Arabia). Complete with a musical overture, intermission and outro (credits back then were very short — pray for that to become the style once again but it will never happen) the movie to the modern viewer seems interminable… binge watching with only one break.

A 35-year-old Charlton Heston stars in the Judah Ben-Hur role which, along with The Ten Commandments, defined his career. And putting aside all his political views (as I do with Clint Eastwood nowadays) he is magnificent. The emotions etched on his face as he goes through his various travails makes the film believable and impactful. Stephen Boyd also gives the performance of his career as Messala but this is clearly Heston’s film and he deserved his Academy Award as did Director Wyler.

However, despite the record 11 Academy Awards given to the film, it is badly dated. The length is tortuous. The romantic scenes between Heston and the beautiful but uninteresting Haya Haraeet as Esther, go on interminably. The bombastic martial music seems to me (now) to be over-the-top. After the exciting sea battle where Ben-Hur fights to save his life the film goes into a long, very boring stretch having to do with Ben-Hur being taken to Rome to meet Caesar. That is followed just before the intermission by the most painfully drawn-out, unrealistic of romantic scenes between Judah and Esther (this is where my youth group, when viewing the film, almost all fell asleep).

What I do really like about this film is its portrayal of Christ. The nativity scene is given much less prominence than in the earlier film and the face of Jesus is never shown. His words are few. But Judah’s first interaction with him is touching beyond words as is the reversal of that scene late in the film. The scene shows both Christ’s compassion and his power. The crucifixion scenes are minimal but touching. The “miracle” at the end is hard to see as “plausible” but still effectively portrayed.

What I do really like about this film is its portrayal of Christ. The nativity scene is given much less prominence than in the earlier film and the face of Jesus is never shown. His words are few. But Judah’s first interaction with him is touching beyond words as is the reversal of that scene late in the film. The scene shows both Christ’s compassion and his power. The crucifixion scenes are minimal but touching. The “miracle” at the end is hard to see as “plausible” but still effectively portrayed.

But the chariot race… Wow, it does makes up for all the time spent getting there as it is just spectacular no matter when it was filmed. The wide-view shots of the race are unparalleled compared to either of the other films. Heston is at his best and even though you know the outcome, one’s heart leaps as the beautiful steads churn and sweat themselves into a true lather and the stunt men perform incredible feats. The film does say that no animals were injured during filming which is surprising given what they were put through. The ending is thrilling and the conclusion of the rivalry is well handled. But the finale to the race is significantly changed in one aspect from both the novel and the 1925 and 2016 films (SPOILER — in this version Messala dies at the end of the race).

The change to the end of this film fortifies the impression that this film is about revenge and righting wrongs. Given the cold war days during which it was made, this was well accepted. The other film versions and even the novel are much more about forgiveness.

My rating (given the dated presentation) – B

Ben-Hur (2016)

So it is time to revisit this war-horse again, right? Romy Downey thought it was. The well-known Christian producer, along with her husband Mark Burnett, had already produced TV’s The Bible and A.D. The Bible Continues, and she felt she could update the 1959 epic and retell “A Story of the Christ” even if they did not include those words in their title. She chose as screenwriter the talented John Ridley (12 Years a Slave and TV’s excellent and sensitive American Crime series) to update Keith R. Clark’s adaptation of Wallace’s novel. Leads were given to Jack Huston (The Longest Ride, American Hustle) as Judah Ben-Hur and Toby Kebbell (Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and Prince of Persia) as Messala. The film was meant to exude quality and also appeal to millennials, committing themselves to significant CGI footage to attract the young people.

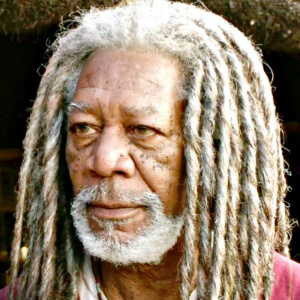

In addition producers hoped the box-office and the quality would be boosted by the presence of the hugely popular and well-respected Morgan Freeman as the dread-locked Ilderim, the Arab owner of the team of Arabian horses that Judah races in the movies finale (a role for which Hugh Griffith somewhat inexplicably was awarded the Oscar in 1959 for Best Actor in a Supporting Role). While the character was present in the other movies, Freeman is given a much enhanced role in this version including the beginning and ending narration. In addition he imparts multiple bits of wisdom to Judah in the second half of the film. Even at 78 years old, he dominates the screen when he appears.

Many scenes which appeared in the previous two movies are eliminated from this version, such as the entire nativity story, Judah going to Rome and the protracted romantic interludes between Judah and Esther. In fact, Judah takes Sarah as his wife quite early in the film. Surprisingly, when he comes back after five years as a galley slave Esther soon rejects him due to his vow of vengeance on Messala and Judah’s violent ways. Jesus appears occasionally in the narrative with mostly non-Biblical words spoken, although they are in the spirit of the teachings of Jesus. And of course everyone speaks English, especially British-tinged English. (True in both of the later films. We will never know about the 1925 film I guess.)

Things that bothered me (a little) were everyone’s pearly white, gleaming, and perfect teeth (those Jewish and Roman dentists were really good), the excessively modern dialogue (for example “I can’t believe this.” and “That’s very progressive.”), public displays of affection (they would have been offensive to the Romans, let alone the Jewish culture), and Esther at one point riding astride a horse in what appeared to be rather tight linen pants. Despite those quibbles I did like John Ridley’s take on the story (at least till the end — see below), which emphasizes forgiveness. It also lobbies for the oppressed and the poor, for love instead of hate, for peace instead of war and for the kingdom of Christ Jesus consisting of riches spiritual instead of material.

Things that bothered me (a little) were everyone’s pearly white, gleaming, and perfect teeth (those Jewish and Roman dentists were really good), the excessively modern dialogue (for example “I can’t believe this.” and “That’s very progressive.”), public displays of affection (they would have been offensive to the Romans, let alone the Jewish culture), and Esther at one point riding astride a horse in what appeared to be rather tight linen pants. Despite those quibbles I did like John Ridley’s take on the story (at least till the end — see below), which emphasizes forgiveness. It also lobbies for the oppressed and the poor, for love instead of hate, for peace instead of war and for the kingdom of Christ Jesus consisting of riches spiritual instead of material.

While this film had the advantage of CGI, it is an expensive technique and its use was modest compared to many CGI movies. Still, the thrill was there and it did away with one of the more unbelievable parts of the 1959 Ben-Hur (that for some reason in the lead up to the sea battle, Judah alone was spared being shackled to the boat so if the boat sank the galley oarsmen had no chance of survival).

This movie also speaks much more of the political unrest of the time of Christ and the zealots who eventually recruit Tirzah. When a zealot accuses Judah of yielding to the Romans Judah says “It keeps the peace.” The zealot, in return, says “You confuse peace for freedom.” Yet Judah nurses one of the fighters back to health, hiding him from the Romans, and later that fighter (un-Biblically) plays a prominent part in the crucifixion.

Issues of idol worship (by Messala) arise and drive Messala to leave the Ben-Hur family (“My Gods are not your gods.”). There are also issues of class conflict and caring for vs scorn of the poor — Judah at one point before he is humbled coldly says to Esther, who has been attending to the poor, “If people just took care of themselves we’d all be better off.” The fact that Messala comes back from his battles as someone who accepts manipulation as a routine way of dealing with people is addressed (Judah tells him when he is pressured into giving up the names of zealots, “I won’t be bullied into this decision.”). All of these issues are not surprising knowing John Ridley was the major screenwriter.

The production values are often impressive. The Roman legions enter Jerusalem not to blaring martial music but to the chanting of the soldiers praising Caesar, with each smaller division restraining a vicious appearing mastiff. It rang authentic to me and one could see why they would put fear into the populace they were ruling. The sets appear authentic, although Jerusalem appears in this film to be built on a mountainside with steep stairways from one level to the next. And the set pieces of the naval battle and the Circus Maximus are truly amazing, even with the knowledge that some of it is CGI. During the chariot race the shots of the crowd are much more detailed than in the other films. Given my profession I also really liked Messala’s deep scar across his right ear — very authentic looking. The addition of snow to exterior shots In Jerusalem was a nice touch, I thought. I think director Timur Bekmambetov (Wanted and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter) made a lot of good choices.

The Chariot race has been criticized as cheaply made, filled with rapid cuts and narrow action shots. I did not agree with those criticisms. Although the expansive, wide-screen shots of the 1959 film are limited, I thought the race was well shot. And the thrill is there. Once again one is amazed at the feats of the stunt men and that fact that collisions were filmed without seriously injuring man or beast. Many of the events in the race are nearly identical to both of the previous films (I did miss the dastardly chariot wheel hubs composed of projecting sharp metal that sawed through Heston’s spokes in the 1959 film).

But in neither of the previous versions did Freeman’s Ilderim play such a significant role, shouting advice from his position in the “in-field” of the Coliseum (as if in the real world Judah would be able to hear him, but… it’s Hollywood). Once again in terms of modern language it is somewhat jarring to hear Morgan yelling “Go… Go… Go” and (with a smile) “Ok, Ok.” But this race involves a little more strategy (supplied by Freeman’s character) then the head-long, all-for-broke racing of the other two films. Both times I have seen the film it was thrilling and I was holding my breath until the ending, predictable as it was. Also, a small aside, the graphics during the end credits are quite innovative.

But in neither of the previous versions did Freeman’s Ilderim play such a significant role, shouting advice from his position in the “in-field” of the Coliseum (as if in the real world Judah would be able to hear him, but… it’s Hollywood). Once again in terms of modern language it is somewhat jarring to hear Morgan yelling “Go… Go… Go” and (with a smile) “Ok, Ok.” But this race involves a little more strategy (supplied by Freeman’s character) then the head-long, all-for-broke racing of the other two films. Both times I have seen the film it was thrilling and I was holding my breath until the ending, predictable as it was. Also, a small aside, the graphics during the end credits are quite innovative.

The movie has been panned by critics, although it is getting better ratings by the general public (66% at Rotten Tomatoes and 5.7 at IMDB). I have tried to understand the reason for the low critic ratings and I do have some problems with the movie as above, plus one big one remaining below. But 27% at RT? I wonder if there is not some snobbery going on both with respect to Roma Downey’s well-known Christian stance and some who felt the movie was harming the reputation of the 1959 classic. Today I read a fairly negative review from someone who had issues with the film’s portrayal of Christ (I did not, although I thought the 1959 film handled it better) but the reviewer then admitted he had never even seen Wyler’s film! Good grief!

The big issue I have with the film (SPOILER AHEAD) is its conclusion. After Judah has defeated Messala he goes to the stables and finds him with one of his legs amputated from being thrown from his chariot, but yet conscious and strong. (The medical side of me rolls my eyes.) As Judah approaches him Messala appears furious and grabs a spear. One wonders if he will impale the defenseless Judah, but at the last moment he cries out and embraces him. This is a man who sent his adoptive mother and brother to an almost certain death, and even did the same to a woman who was in love with him and who he had known his entire life. Now, after years of no thought for their well-being, and then making every effort to kill Judah, he suddenly has a complete reversal in his attitude? The last scene of the film, which I will let you see for yourself, is so gratingly a “fairy tale ending” that it makes me cringe. And no, none of the “180 degree turn” by Messala is attributed to his life being changed by Christ or any other radical event… it just happens. This is the kind of forced conclusion that gives so many Christian movies a bad name.

So I recommend the movie for the thrill of the naval battle scenes and, of course, the chariot race in the awesome Circus Maximus. And see it for the excellent exchange of ideas and, if you wish, contrast its themes of forgiveness and mercy to those of either of the two other films. I was touched on both viewings at Christ’s compassion in what were politically turbulent and dangerous times. See it for Morgan Freeman’s character of Ilderim who is enjoyable throughout. See it but forgive the scriptwriters (or who can we blame it on?) for their ridiculous ending. I think you will be blessed and entertained.

My rating (discounted only by the discordant ending) – B+