The 2003 film Oldboy (Oldeuboi), a Korean production directed by Park Chan-wook, is one of those disturbing explorations of humanity that leaves you with something akin to a post-Lynchian (good Lynch) hangover that lingers for several months after viewing (for context I saw the movie in September of 2018 and I am still processing it). At first I was completely shocked and disturbed — a little empty/drained in the immediate aftermath of something so sinister. But it kept gnawing at me — as exceptional, not merely shocking, art is prone to do. The movie begs for further analysis, thought, and confrontation; and confrontation is at the core of Oldboy.

Your gravest mistake wasn’t failing to find the answer. You can’t find the right answer if you ask the wrong questions. – Lee Woojin (Oldeuboi)

Before proceeding too much further I have a few disclaimers: 1) As alluded to above, this movie conjured similar feelings to a Lynch film and for a lot of the same reasons — the sex and violence are disturbing components of the movie. I am typically not the squeamish sort and found myself shutting my eyes at a particular point; believe me, that does not typically happen. With that in mind, combined with the dark territory the movie enters, you may want to pass. 2) This review/essay will be filled with spoilers, so if the above disclosure does not apply and you plan on seeing the movie you may want to stop now and come back after viewing. 3) I do not touch the Spike Lee Americanization of Oldboy. Nothing in here is reflective of what that cast and crew put together.

An Ode to Grecian Tragedy (At Least of the Freudian Variety)

After the initial shock of the film (which is less about the final reveal, and more about the final choice) the lightbulb moment that put it in perspective was putting it in the context of the Oedipus myth, and a highly Freudian approach to it — read: major incestuous psychosexual ickiness. Not only is a slightly altered version of this ancient tale employed through a contemporary context, but we are brought into the action and are implicated in the moral crime itself.

Major spoilers coming up: Oldboy follows the revenge movie structure almost perfectly. It truly lulls you to sleep for the final twist. Even the final twist is, initially, a question of whether or not Oh Dae-Su (the protagonist) will get his revenge, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

The movie opens with a drunken Oh Dae-Su in a police station cursing people out and starting all sorts of nonsense. We learn that he is married and the father of a young girl, and that he’s not the greatest guy in the world. Once released from the police station he is kidnapped and imprisoned for the next fifteen years. Once he is released he is given five days to find his captor. Knowing the type of man Oh Dae-Su was there are almost innumerable people who could have done this to him, so the mystery in the midst of bloody retribution becomes who and why.

The movie opens with a drunken Oh Dae-Su in a police station cursing people out and starting all sorts of nonsense. We learn that he is married and the father of a young girl, and that he’s not the greatest guy in the world. Once released from the police station he is kidnapped and imprisoned for the next fifteen years. Once he is released he is given five days to find his captor. Knowing the type of man Oh Dae-Su was there are almost innumerable people who could have done this to him, so the mystery in the midst of bloody retribution becomes who and why.

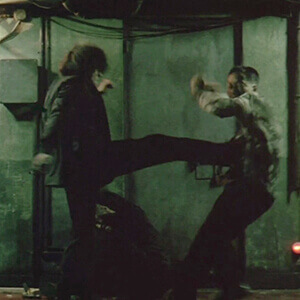

While locked up his wife dies, and his daughter ends up adopted — this is all disseminated to him via a television in his room. Upon his release he meets a woman, Mi-Do, and eventually they end up falling in love with one another. The psychology of this, he the protector and she the healer, could be a whole essay in and of its own accord. Their falling in love is both fascinating, bizarre and strangely believable. On Oh Dae-Su’s path towards revenge he violently mows down hired goons and eventually makes his way to the source of this plot against him, his former schoolmate Lee Woojin. Again, the initial twist looks as though Lee Woojin has captured Mi-Do through deceit and her life is in his hands, and Oh Dae-Su is not strong enough to defeat Lee’s bodyguard. There was no Chekhovian gun in an earlier scene that indicates any way out, and the movie seems like it’s going to end in the most pessimistic way possible… until it gets worse.

Lee, it turns out, was the younger brother of a girl Oh Dae-Su flirted with in school. Later Oh Dae-Su caught Lee and his sister in the act of incest. Lee elaborates that rumors spread, his sister became pregnant and she killed herself from the shame. Lee was completely in love with his sister and blamed Oh Dae-Su for her death, now the movie looks like a strange revenge tale of incestuous lovers, and this is where Lee explains that he did not just want to punish Oh Dae-Su, but wanted him to truly experience what it was like to have feelings for someone that you were not supposed to. Lee had killed Oh Dae-Su’s wife, and through a surrogate, adopted his daughter, raising her and conditioning her through hypnotism and strange behavior modifying practices. During this time Lee was doing the same things to Oh Dae-Su, conditioning him, drugging and hypnotizing him. Meeting and falling in love with Mi-Do was not an accident, but was Lee’s ultimate revenge because Mi-Do is Oh Dae-Su’s daughter.

Post-Truth Actualized

Park Chan-wook’s direction is masterful in this. He understands the expectation of the audience and creates such a furious and reactive pace that you do not have time to piece the mystery together. He manipulates us, both to not see the twist coming and to be complicit in the moral failure of Oh Dae-Su. This is what makes the movie so disturbing and yet powerful as an internal lens. It is a simple thing to dismiss and deny our capacity for evil, to think of ourselves as “good” people when we are not faced with such an extreme moral conflict. Chan-wook actually makes us root for the love between Oh Dae-Su and Mi-Do, he creates a scene charged with the erotic as the two become lovers and invites the unwitting viewer to be complicit in this act. When the reveal is finally made we are not just shocked, we are attempting to make sense of our own guilt.

Chan-wook could end the story there and the film would be powerful and challenging, but he takes us another step further. The film ends with a choice. Oh Dae-Su’s daughter remains ignorant of their true relation, and is still in love. He must determine what to do with this mess. The full force of the film is in its forcing the viewer to deal with the nature of truth, solipsism*, moral subjectivity and how we choose to establish moral boundaries (either as transcendent or situational). Oh Dae-Su’s final choice is what makes the movie an unflinching look at human nature. We are not given the ambiguity of “what-ifs” that could have been left us (in a way that lets us off the hook), but we see his final choice and have to ask ourselves what we would have done. Oh Dae-Su tracks down the hypnotist who had programmed Mi-Do and himself to fall in love, and has her wipe his mind of the truth, so that they can continue on in ignorance, not having to contend with the horrible reality of things.

In an age of personal truth, or post-truth, Chan-wook is challenging us to see the denial of transcendent ideals for what it is. We are constantly hypnotizing ourselves to realities in order to justify, validate, or, at its worst, disintegrate morality altogether.

Theory Lived Out

Oldboy moves theoretical logic into the real world, stemming from a denial of anything foundational i.e. there is no capital “T”-truth, only lived-out and experiential personal truth. In the progressivist school these personal truths lead towards moral grounding. As we progress societally our self-knowledge improves, our knowledge of others improves, and our morality is shaped into something greater and more fluid than the “rigidity” of morals grounded in the transcendent. There are legitimate attempts to marry traditional and progressive views with movement towards the transcendental. What Chan-wook is calling us to wrestle with, however, is the centrality of humanity that typifies progressive theory i.e. human progress leads to transcendence vs. human progress as the pursuit of the transcendent. It seems, at first glance, to be a subtle difference, but this is the choice that Oh Dae-Su makes.

What it reveals is that moving forward is not always progressive, but can actually become regressive. Or as C.S Lewis puts it: “Progress means getting nearer to the place you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turn, then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man.”

I do not want to make a case against progress, or the progressive theories in general. What I think Oldboy proposes is a need for being careful with what we progress towards. And what we progress towards is dependent on who/what takes the central role of importance.

Closed Loop Sexuality & Solipsism

When we enter into these sorts of self-produced truth structures we enter into a sort of solipsistic framework. Solipsism is a logical conundrum that covers the idea that “only I can know that I exist.” It spills out of Cartesian “I think, therefore I am” ideologies, and really took off as existentialism began to develop. The application of solipsism in this case is from the standpoint of moral and/or truth construction. This, in and of itself, is a lengthy topic that dives into the realm of post-truth and “my own truth” at length. These are messy arguments to enter into, and cases such as Oldboy challenge this narrative of self-constructed values, while not necessarily giving a clear answer for an alternative. We all feel icky about the whole situation, but, at the end of the day, why?

As Christians we can begin to answer this in the context of what we build our ideas of truth off of — a transcendent (and imminent) God who is, by his very nature, truth itself. What this means is that, as Christians, we believe in capital “T” truth and know exactly why this brokenness pulls us away from what is good. This all plays out in a rather fascinating sexual/love metaphor in Oldboy.

Incest is nothing new to the ancient tragic stories. Where this changes in Oldboy is that Lee, the story’s antagonist, decontextualizes his sister from moral norms and recontextualizes her as someone whom he deeply loves. Sister becomes just another word, and he validates their relationship as transcendent of these sorts of fetters in and of itself. This is the ultimate danger of solipsism — that important and legitimate norms are simply brushed aside as mere abstractions that do not apply if you place a different abstraction as higher (you could read idol for abstraction if you wish, they are simply no longer carved but have become verbal & written symbols of that which we mistakenly replace THE transcendent one with).

Lee’s (and eventually Oh Dae-Su’s) choice is to misunderstand a holistic view of love, by placing two singular aspects together and ignoring the rest (those being the love of family and the connection between love and sex). Even this view of sex is extremely limited (as is Oh Dae-Su and Mi-Do’s) to passion and pleasure. There are much more devoted thinkers than myself who have elaborated on what a holistic sexual relationship is, and I would recommend seeking them out for a clearer picture. The whole point of this is merely to point out the destructiveness of distilling something into its components, choosing a few of those components to embrace, and pretending that the remainder of the whole will be unaffected/ing. In the case of incest we literally see a procreative act turn into something destructive — at the genetic level and looking at the broader sense of marriage as a form of community building and expanding. This is the very same danger of equating and substituting truths for Truth.

“No tree can grow to Heaven unless its roots reach down to Hell.” – Carl Jung

Oldboy certainly reaches down into the pits of Hell, and it would be quite easy to become trapped there after watching this film. In the same respect, to be able to enter into this, to explore the truth behind our more malevolent selves (because, if we are honest, we can easily see our own reflections within this film), there is wisdom to be gained.