The mass media, with their cult of celebrity and their attempt to surround it with glamour and excitement, have made Americans a nation of fans, moviegoers. — Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism

‘What is the nature of the search?’ you ask. The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. To become aware of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair. — Walker Percy, The Moviegoer

If ever there were a movie in despair it would be Mary Poppins Returns. From the minor editorial faux pas to the films emotional disjointedness it is hard to see this as much more than an empty shell built on our collective nostalgia (a well Disney seems to continue returning to as of late). I think, however, that if we take one step further and move beyond the surface analysis, what we might find instead is an odd sort of window into our rather anxious, rather depressed society whose population craves a certain level of celebrity… and may in fact sincerely think it to be the path of personal salvation.

If ever there were a movie in despair it would be Mary Poppins Returns. From the minor editorial faux pas to the films emotional disjointedness it is hard to see this as much more than an empty shell built on our collective nostalgia (a well Disney seems to continue returning to as of late). I think, however, that if we take one step further and move beyond the surface analysis, what we might find instead is an odd sort of window into our rather anxious, rather depressed society whose population craves a certain level of celebrity… and may in fact sincerely think it to be the path of personal salvation.

It is fascinating how close Jennifer Egan’s assessment of this came. In her Pulitzer Prize winning novel, A Visit from the Goon Squad, about a not too distant future with a generation tired of absolute manipulation for the sake of profit and in search of the authentic, a central part of the story line gathers around a record label attempting to promote a genuinely authentic artist – the paradox is delicious. Where Egan misses the mark in her prophetic piece(1) may be in the power of our cynicism. I mean this as no slight, but think of who our great authentic artists of the day are. They are the highly marketed spectacles whom we mistake a sort of callow vulnerability(2) for true authenticity. They sing vague lyrics about relationship mistakes, they are in the public eye being scrutinized for every single thing they do and say… but are defiant towards their critics (especially on moral issues).

We have embraced this as authentic, as heartfelt and sincere, and we have justified it because we are in fact in pursuit of the very same possession. We mistake the connection we may feel to lyrics, or a press clipping, with the building of community with an other. We think that if people know about us they will know us. At our core we are seeking adulation as a means to receive love.

What does any of this have to do with Mary Poppins Returns? The answer to this is both explicit in the films ending (yes, this essay contains spoilers), and subtly (or maybe not so subtly) laced throughout the film.

Not So Parallel Structures

The picture begins to form when analyzing the bigger narrative picture. In it we see the return of Michael Banks, now grown up and inheritor of the Banks’ family home, he has lost his dreams of becoming an artist – and his wife. He is left to care for their three children (which we learn he never really could because his wife did that), to tend the financial matters (which we also learn he never really could because his wife did that), and earn a living (which is a confusing point because his career as an artist never seemed to go anywhere and we

have no idea when he took the job at the bank – did he simply live off of his inheritance until the Great Slump came around? I suppose this is the most logical assumption). Jane, on the other hand, has made her way as a labor organizer living in a flat on the other side of town – obviously this is a little wink and nod to Mrs. Banks in the original Mary Poppins (yes, Jane is just as cheerful and smiley) which is another of the over-pressed nostalgia buttons.

Michael’s three children seem to know how to make a dollar stretch and solve a lot of their own problems. Although we are never really shown any true need for help, Mary Poppins just happens to show up on a kite. Throw Jack, the lamplighter who apprenticed under Bert, into the mix and we have a mirrored image of the original Mary Poppins… on the surface.

Where the film breaks from the original is the typology of the problem Mary Poppins is brought in to solve. In the original we followed two lonely children in the home of a caring, but not loving father who repressed and oppressed his household under the guise of order. Mr. Banks failed to pause and love his family well. Mary Poppins, through her irreverent adventures was able to reveal the truth to him, to Michael, and to Jane – the truth being that Mr. Banks really did love his family, he just needed to pause and see the moments that actually mattered a little more. Some of this lingers in the film, the notion of a child’s wisdom, the ability to see the magic of our world not yet worn down by “adult things.”(3)

In Returns Michael is about to lose his house, and his corrupt employer (Colin Firth), the man running the bank in his uncle’s stead,(4) is seeking to possess as much lost property during these hard times as possible (the Banks’ residence included). Michael and his children have a good relationship, when he loses his temper he pauses to apologize, he tells them he loves them and all about how wonderful they are. In essence this family already has a spot of the magic Mary Poppins is meant to bring. The problem truly lies outside of the reach of this archetype. Look at other similar models – Nanny McPhee, The Five Children and It, and even The Chronicles of Narnia. These stories are meant to address deeper relational problems within families. The magic they stumble upon, or have brought into their very homes, is meant to challenge the rigidness or selfishness within a family in pursuit of a higher good.(5)

They were never meant to solve the practical problem of money, but rather the impractical: that we sometimes desire it more than people. The movie feels like, by throwing enough celebrity power (Emily Blunt, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Dick Van Dyke, and Angela Lansbury), at the audience and haphazardly slapping together a “coherent” script, nobody will notice the complete and utter emptiness of the film. The funny thing being that, where the original Mary Poppins was unconcerned with money, this new one seems consumed by it – from the film’s production to its very plotline.

They were never meant to solve the practical problem of money, but rather the impractical: that we sometimes desire it more than people. The movie feels like, by throwing enough celebrity power (Emily Blunt, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Dick Van Dyke, and Angela Lansbury), at the audience and haphazardly slapping together a “coherent” script, nobody will notice the complete and utter emptiness of the film. The funny thing being that, where the original Mary Poppins was unconcerned with money, this new one seems consumed by it – from the film’s production to its very plotline.

The intent was to sweep us all up in the grand nostalgia, the song and dance, the fun scenes combining live actors with animated characters. We were meant to get caught up in remembering the heart of the original movie so that we might not see the heart of the contemporary one. The film itself opens with Emily Blunt and Lin-Manuel Miranda thanking audiences for coming to see the show. This sort of direct appeal from the hottest musical star in the land and one of the most charming actresses in Hollywood was exactly what it looked to be on the surface: the power of celebrity at work over the passively viewing and receiving audience.

Dyke Ex Machina

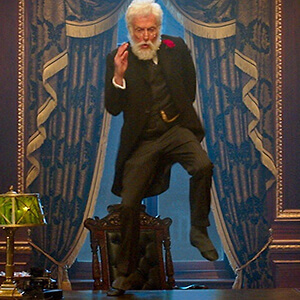

Ultimately the movie falls on poor plot devices all the way to the end in which we are treated with the off brand version of the Deus ex machina. Instead of God opening up the heavens and pouring out a miracle to save Michael Banks and his family from the hungry wolf (Firth), Dick Van Dyke(6) shows up. This could have worked. This could have been something worked into the script earlier, but Van Dyke is completely absent from the film (save that Firth is mentioned as his nephew) until he appears from behind closed doors, just past the last stroke of midnight, when all hope seems lost. This is the celebre hominem ex machina.

This is not just poor writing. This is a reinforcement of this perverse nostalgia(7), of the idea that our American Idols can and will save us; or worse, that by becoming those we hold as idols we can rise above the pain and toil of common life (that financial and personal problems will magically disappear). This is the new salvation and Returns is a window into its heart. From this standpoint the film becomes very interesting and worth more attention. Note: not because the film is good, but because it lends itself especially well to sociological insights as to what we value as a culture.

This becomes even more interesting when you think of the tie-ins to social media use, the psychological drive for affirmation via “likes” or the false sense of intimacy created by screen-to-screen interactions. Then there are the studies that suggest the younger generations are the most likely to think they will become famous (I’ve personally had several seven year olds tell me in total seriousness that they want to be YouTubers when they grow up). There is a warning in this, and it is not that celebrity, entertainment, or social media are bad(8) per se; it is, instead, that we ought to be more weary of who and/or what we turn into our gods. If we are not we may be the same empty shell that is Mary Poppins Returns, filled with song and dance but little else.

(1) This is not a swipe at Egan or her work. Obviously she did not mean this as a prophetic novel, but a culturally descriptive one. In this sense she is completely on target, and, let’s be real, the whole scope of her incredible novel is much larger than this singular point. I think, maybe, we are all a bit surprised that things have gone in the current direction rather than the one she envisioned. Then again, maybe the marketing gurus have always been one step ahead of the game. I know I’ve drawn water from this well often, but David Foster Wallace’s essay E Unibus Pluram is worth the read.

(2) Confessional style song lyrics, “revealing” interviews, and the fact that memoir is the top selling non-fiction genre make it hard not to notice the exploitability of celebrity exploits. At a certain point one has to wonder whether or not poor celebrity relationships are not intentionally (or maybe even as some bizarre form of subconscious direction) sought out for the sake of 1) intrigue and 2) the marketing capital that comes with a bad breakup (a third option – source material for the next creative project – could apply to several performers). Anyways, this is an entire topical essay in and of itself with a long history that extends well beyond our contemporary era (think of the literally made-in-Hollywood marriages/relationships between studios stars). The point is more that this is a sort of cultural sickness that has cleverly disguised itself as self-aware causation and solution in one fell swoop, all with the goal of marketing to us via a sense of intimacy between self and favorite performer. Think, how intimate can a relationship be if the closest you get is a concerts front row, with its fenced off gap between you and the stage, and a team of security ready to throw you back to your seat?

(3) There is a subtle distinction that both films stay true to – “adult things” are not inherently bad, in fact they are vital, it is bad when it becomes all consuming and the world becomes a drab gray appointment book of absolute structure or a balance book with the only end sought being profit. From time to time we need to step back and relish the magnificence of the mundane. There are glimpses of this in the film, but they feel so rushed. As is the problem with all poor musicals the songs act like a fresh coat of paint over structural damage.

(4) Yet another nod to the original film, here is the nephew of the owner of the bank in which Mr. Banks worked at.

(5) This is a highly simplified definition that could probably use its own deep dive as well.

(6) Dick Van Dyke was not just Bert in the original film, but was also Mr. Dawes Jr. the banker, who is the uncle of Firth’s character.

(7) Not all nostalgia is a bad thing, but when (knowing that it is a strong and pulling emotional response to things valued, loved and lost) it is used in an overt attempt to profit over adding cultural value there is cause for the label of perversion.

(8) I am partial to the Andy Crouch phrase that this is not good or bad, but it certainly is not neutral.