Many of us have ambivalent feelings about the wars our country fights. Even if we have concerns for the justifications given to our troops to be in harm’s way overseas, we cringe at the potential damages to their physical and mental health, let alone the chance that they may pay the “ultimate price.” When we see these men and women return from war zones we may struggle with our attitude — are they pawns in international conflicts waged by men and women who will never themselves be in danger, or are they procuring with their blood and well-being the freedoms we civilians take for granted? We want to believe that their service is “worth it.” We want to believe our soldier’s actions are always noble and honorable. We want to believe they are fighting for what is just. We want to believe our soldiers are the “good guys” and that every one of them deserves to be called “hero.”

The Victory Tour

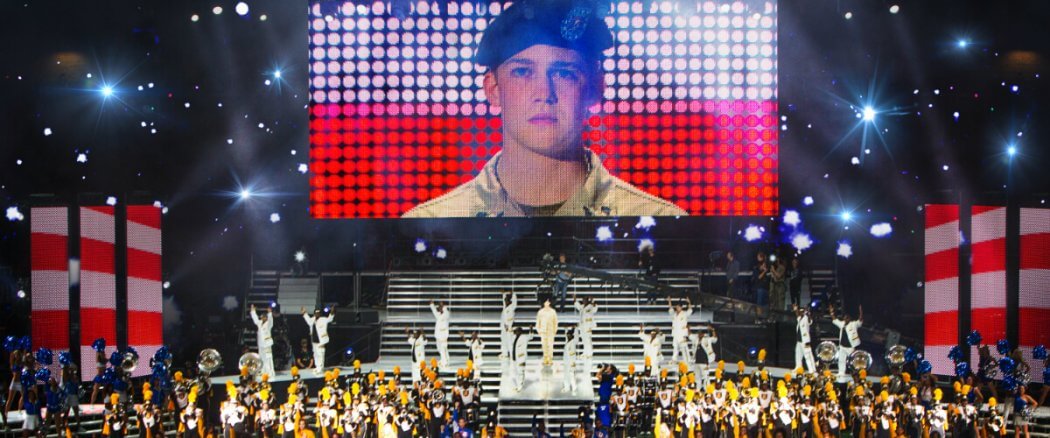

Based on Ben Fountain’s acclaimed 2012 satirical novel of the same name, Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk tells the story of 12 hours in a 19 year old soldier’s life. In his first tour overseas, Billy Lynn has a few critical moments of combat captured by an embedded Fox news crew. When that video of Billy’s moment of undeniable bravery is broadcast, it goes viral. Attempting to save the life of his sergeant during a firefight against Iraqi insurgents, Billy Lynn’s actions enthrall the American public and make Billy and his company, Bravo, a symbol of national pride and what is “right” about the Iraqi conflict. Realizing the potential of this story, the US Department of Defense brings the surviving men of Bravo Company back from deployment for a two week “Victory Tour” to be feted as the best America has to offer. They are ported from one venue to the next to be displayed and honored… and to drum up enlistments and political support for the war effort. The tour culminates at the halftime show of a major professional football game on Thanksgiving Day. (In the novel the game clearly takes place at the Dallas Cowboy Stadium in Arlington, but in the film, despite the prevalence of “Navy and Metallic Silver” stars and the easily recognizable Dallas cheerleader outfits, the team is not named and the exterior views of the stadium are not the Dallas Cowboy Stadium… legal issues I am sure.)

For this final stop of their Victory Tour before being shipped back to combat duty, Bravo is the guest of the team’s owner Norm Oglesby (clearly, other than for his name, Cowboys owner Jerry Jones). They are to be featured in the game’s halftime show, sharing the stage with Beyoncé and Destiny’s Child (of whom we only see distant or rear views of stand-ins). Norm is their host and is everything you would expect (“You get in a fight with Norm, you better be wearing a cup”). At the stadium, more importantly than Norm, are the (Dallas) cheerleaders — described from the novel and portrayed in the movie as “the life-sized sampler of rapturous female flesh with all colors, all flavors of sculpted tummy… and such breasts, Oh Lord…” Each of the seven surviving members of Bravo fantasize a one-on-one session with one (or more) of these icons of lust. In addition, they have been joined by a movie producer Albert (played less sleazily than expected by Chris Tucker, in his first feature role since 2012’s Silver Linings Playbook). Albert is attempting to sell the movie rights of their story to Hollywood, promising Bravo he will get them as much as $100,000 per soldier for the rights to their story.

For this final stop of their Victory Tour before being shipped back to combat duty, Bravo is the guest of the team’s owner Norm Oglesby (clearly, other than for his name, Cowboys owner Jerry Jones). They are to be featured in the game’s halftime show, sharing the stage with Beyoncé and Destiny’s Child (of whom we only see distant or rear views of stand-ins). Norm is their host and is everything you would expect (“You get in a fight with Norm, you better be wearing a cup”). At the stadium, more importantly than Norm, are the (Dallas) cheerleaders — described from the novel and portrayed in the movie as “the life-sized sampler of rapturous female flesh with all colors, all flavors of sculpted tummy… and such breasts, Oh Lord…” Each of the seven surviving members of Bravo fantasize a one-on-one session with one (or more) of these icons of lust. In addition, they have been joined by a movie producer Albert (played less sleazily than expected by Chris Tucker, in his first feature role since 2012’s Silver Linings Playbook). Albert is attempting to sell the movie rights of their story to Hollywood, promising Bravo he will get them as much as $100,000 per soldier for the rights to their story.

12 Hours in a Life

Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk’s narrative is of that one day — their final day stateside — but with numerous flashbacks as Billy contemplates what it all means. (Despite the trailers which imply this is a combat film, there are only a few war sequences, gripping as they are.) The novel was told in the first person and that is how the movie plays out too, with Billy Lynn played in a star-making turn by British new-comer Joe Alwyn, who has his Texas accent down to every “Ahh” for “I” and dropped “g” for each “…ing.” Billy is trying to make sense of the sudden adulation of almost everyone, when just a year before a judge in his hometown told him his choice was to go to jail or “volunteer” for the Army. From a humble background in small-town Texas, he has been thrust onto America’s stage for this one moment in his young life. And Billy is trying to cope with it all. Flashbacks tell of his two-night leave from the “Tour” to see his family with mixed messages given to him. All of them, along with his small community, are awestruck by his sudden celebrity other than for his loving but cynical-about-the-war sister — a nice turn by the increasingly impressive Kristen Stewart, best known for the Twilight series. (There is chatter of Stewart being nominated for a best supporting actress Oscar for this role and I would agree it would be deserved.)

Touching on numerous false notes and hypocrisies of our times, especially those involving the Middle Eastern conflicts, Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk skewers many of America’s cherished notions — patriotism, wealth, politics, the film industry, chosen nation status, heroism, football, religion, the American success story and, especially, the need for America to have heroes. Missing Billy’s internal narrative that drives the wryly funny and engrossing 320 page novel, the film may be harder to love for those who have not read the book. But there is tension as to whether Billy will meet a Dallas cheerleader (he does — Gotham’s Makenzie Leigh who is a little too young and doe-eyed to pull off cheerleader “Faison”) and whether they form a long-lasting relationship; whether Bravo will actually get that movie and the 100 large paycheck; whether they meet and touch Beyoncé; whether the company survives a confrontation with roadies from the half-time show; whether Bravo challenges Norm regarding his will-it-make-money-for-me faux patriotism; whether he listens to his sister’s siren call to abandon the Army and his Bravo brotherhood; whether his company buddy Crack chokes to death a smart-mouthed frat boy; and whether Billy can endure one more rich old white man (from the novel) “make free with Billy’s young body, kneading his arms and shoulders, clutching his wrists, clapping a manly hand to his back… they gush… they swear allegiance and undying gratitude.” Again from the novel and illustrated by the film, “Billy never noticed how fake it all was until he had done time in a combat zone.” Bravo’s resignation to what they do and their disillusionment that America really understands what they are asking of them is sobering. “No amount of lecturing will enlighten them (American citizens) as to the state of pure sin toward which war inclines.”

Touching on numerous false notes and hypocrisies of our times, especially those involving the Middle Eastern conflicts, Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk skewers many of America’s cherished notions — patriotism, wealth, politics, the film industry, chosen nation status, heroism, football, religion, the American success story and, especially, the need for America to have heroes. Missing Billy’s internal narrative that drives the wryly funny and engrossing 320 page novel, the film may be harder to love for those who have not read the book. But there is tension as to whether Billy will meet a Dallas cheerleader (he does — Gotham’s Makenzie Leigh who is a little too young and doe-eyed to pull off cheerleader “Faison”) and whether they form a long-lasting relationship; whether Bravo will actually get that movie and the 100 large paycheck; whether they meet and touch Beyoncé; whether the company survives a confrontation with roadies from the half-time show; whether Bravo challenges Norm regarding his will-it-make-money-for-me faux patriotism; whether he listens to his sister’s siren call to abandon the Army and his Bravo brotherhood; whether his company buddy Crack chokes to death a smart-mouthed frat boy; and whether Billy can endure one more rich old white man (from the novel) “make free with Billy’s young body, kneading his arms and shoulders, clutching his wrists, clapping a manly hand to his back… they gush… they swear allegiance and undying gratitude.” Again from the novel and illustrated by the film, “Billy never noticed how fake it all was until he had done time in a combat zone.” Bravo’s resignation to what they do and their disillusionment that America really understands what they are asking of them is sobering. “No amount of lecturing will enlighten them (American citizens) as to the state of pure sin toward which war inclines.”

Paid Patriotism

Interlacing the troops being honored in such a central way with an NFL halftime extravaganza may have seemed a stretch until the news came out in 2015 (three years after the novel was written) that the NFL and other professional sports were paid over $10 million with taxpayer dollars to host patriotic tributes and displays. If payments to NASCAR were included, the total ballooned to more than $100 million. Former Army Ranger Rory Fanning, who has become a vocal critic of America’s foreign wars, opines “It’s a box-checked kind of thing. The way you support our soldiers is by asking them questions about what happened when they’re overseas and to talk to them about what they did. I don’t think sporting events is a proper place for that. There’s very little critical discussion. These things have a way of washing over all those questions.” The NFL did return over $700,000 of that money. “Paid patriotism”? Small wonder that soldiers feel they are being used as pawns in so many different ways.

Displaying Their Craft

Three actors from the large cast besides the lead and his sister deserve special mention. Steve Martin (in his first major feature, non-comedic role in many years) is just right as Jerry Jones… err, Norm Oglesby. Commanding, powerful, glad-handing, euphemistic-spouting and quickly judgmental. I love it when he says with fake sincerity, “Your story, Billy, no longer belongs to you.” And later, “You have given America back its pride,” To which Billy thinks (per the novel), “America? Really? The whole damn place?” Martin is masterful in his portrayal of an obnoxious American icon.

Likewise Vin Diesel (he of all the Furious films) makes memorable his few minutes of screen time as Billy’s veteran platoon brother, Shroom (his moniker coming from his fondness for psilocybin fungi). A reader of philosophy and student of Eastern religions, he is a believer in dharma telling Billy, “If a bullet is going to get you, it’s already been fired.” Smiling, seemingly content and mystical, one totally believes his character’s fatalism, even as one has trouble believing that many such people serve in the armed forces. He makes a special impact when (MILD SPOILER) he unexpectedly and mystically appears to Billy in some of the final scenes of the film.

Likewise Vin Diesel (he of all the Furious films) makes memorable his few minutes of screen time as Billy’s veteran platoon brother, Shroom (his moniker coming from his fondness for psilocybin fungi). A reader of philosophy and student of Eastern religions, he is a believer in dharma telling Billy, “If a bullet is going to get you, it’s already been fired.” Smiling, seemingly content and mystical, one totally believes his character’s fatalism, even as one has trouble believing that many such people serve in the armed forces. He makes a special impact when (MILD SPOILER) he unexpectedly and mystically appears to Billy in some of the final scenes of the film.

But the revelation of this cast is Garrett Hedlund with whom I was not that impressed in Unbroken and Tron. Playing Sergeant Dime, he is brusk but caring, cynical but insightful, and he visibly loves each of his men. He can be dryly hilarious (as he reassures the horrified, well-to-do, elite football matrons watching Bravo devour their meal like animals in “The Club” for box seat owners), “It’s chill. Just keep your hands and feet away from their mouths and you won’t get hurt.” And the next moment he will turn icily biting, “Everybody supports the troops… support the troops, support the troops, hell yeah we’re so f_ _ _ing proud of our troops, but when it comes to actual money? Like somebody might have to come out of pocket for the troops? Then all the sudden we’re on everybody’s tight-ass budget. Talk is cheap… but money screams.” Hedlund pulls off the character and makes you understand why Billy, despite all his misgivings, sees Bravo company as his true family. Hedlund’s characterization is noble and played with authority and authenticity.

The Dawn of New Technology

Ang Lee (Life of Pi, Brokeback Mountain) directed Billy Lynn… and it must have been a difficult challenge to accept helming a film that was based on such a cerebral book. Much was made of his shooting the film at 120fps, 3D with “native 4K rendering” (having never gone to film school I cannot tell you exactly what that means other than if projected in accordance to those specs, the image, even when the camera pans, is said to be amazingly smooth and hyper-realistic with an incredible depth of field). To compare, Peter Jackson doubled the frame rate of The Hobbit from the normal 24 to 48fps, so obviously 128 fps is a new horizon. Unfortunately, there are only two theaters in the US (in New York and Los Angeles) that can show it 3D at that frame rate. And reviews of the process were decidedly mixed, with many feeling the images caused them to become disoriented and even nauseous. Lee is still a vociferous proponent of the technology and I suspect we will see it in his future films.

As for his direction of the movie itself, I am a big admirer. To touch on the humor, the confusion, the conflicting themes, the lack of anyone who really feels they are a “hero”… Lee does a superb job. There are some false moves such as including Billy’s father (in a wheelchair) without any explanation of his condition (another complex plot line in the novel) or minimizing the effect of Shroom’s fatalistic outlook on Billy, but overall Billy Lynn… is a tender examination of some of the complexities of the American soldier today. (What a comparison to Hacksaw Ridge.) By the way, in case you were wondering, the title refers to the “long” walk Billy Lynn needs to make at the halftime of the Thanksgiving game to be lauded as the new American hero. And less concretely, I believe it pertains to the “long halftime walk” of Billy as he becomes a more perceptive and wise man. The journey is difficult — especially when forced to accept labels you feel are ridiculously inappropriate.

As for his direction of the movie itself, I am a big admirer. To touch on the humor, the confusion, the conflicting themes, the lack of anyone who really feels they are a “hero”… Lee does a superb job. There are some false moves such as including Billy’s father (in a wheelchair) without any explanation of his condition (another complex plot line in the novel) or minimizing the effect of Shroom’s fatalistic outlook on Billy, but overall Billy Lynn… is a tender examination of some of the complexities of the American soldier today. (What a comparison to Hacksaw Ridge.) By the way, in case you were wondering, the title refers to the “long” walk Billy Lynn needs to make at the halftime of the Thanksgiving game to be lauded as the new American hero. And less concretely, I believe it pertains to the “long halftime walk” of Billy as he becomes a more perceptive and wise man. The journey is difficult — especially when forced to accept labels you feel are ridiculously inappropriate.

The Brotherhood of Combat

Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk points to how difficult it can be to deal with the consequences of sending young men to war, and how feeble are our attempts to give them comfort. It points to how combatants feel only they can understand what they have been through. In the end, as difficult as their military service might be (in the novel’s acerbic voice, “Wear this, say that, go there, shoot them, then of course there’s the final and ultimate… be killed”), the brotherhood (and sisterhood) of those who endure warfare is beyond the comprehension of most of we civilians. We need to be careful how we presume to know what they have experienced. We need to sit down with vets and ask them if they want to talk about what they went through. We need to be interested, not just give a pro forma pat on the back with a “Thank you for your service.” Perhaps all we can really do that is meaningful is pray for them and accept the fact that we cannot know where their mind might be. We need to pray for our leaders and support every attempt to not wage war. The damage to our children and our children’s children caused by our country’s continuing and constant state of war is beyond our comprehension. God, forgive this blessed nation for our enticement by the evil of war.