In 2014 the world got a little less interesting with the retirement of one of the greatest directors of the moving picture. Animation’s greatest auteur, Hayao Miyazaki, announced he was stepping down from his visionary and meticulous work at Studio Ghibli. With its final production, 2016 Oscar-nominated When Marnie Was There, Ghibli hit the pause button on creating new work and is said to have gone into “restructuring” mode.

Cartoons? Really?

First, a little must be said about Japanese animation (or “anime”). As a medium it is as diverse in style and genre as the US filmmaking industry. There are adult dramas, teen romance and children’s stories. There are surrealist fantasies, cyberpunk science-fiction, period epics, and erotica. The animation can be CG, 2D hand-drawn, hyperrealistic, absurdly exaggerated, painterly, or a mixture of all of the above (sometimes in the same frame).

American audiences who may have been exposed to Japanese pop culture through Pokémon or (if you’re old) Robotech are only scratching the surface on a medium rich in history and craft. The craft of hand-drawn anime is especially distinct from the kind of work US animation studios have churned out lately (*cough* Disney). While the earliest Japanese animators were inspired by the earliest Disney work (like Snow White), the two quickly diverged to the point where drawing equivalencies is almost insulting to the work of masters like Miyazaki. Japanese animation owes more to Japanese filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa and 1000-year old traditions of calligraphic line-work and pictorial scrolls than to The Land Before Time parts 1-14 or Cinderella 3: A Twist in Time.

American audiences who may have been exposed to Japanese pop culture through Pokémon or (if you’re old) Robotech are only scratching the surface on a medium rich in history and craft. The craft of hand-drawn anime is especially distinct from the kind of work US animation studios have churned out lately (*cough* Disney). While the earliest Japanese animators were inspired by the earliest Disney work (like Snow White), the two quickly diverged to the point where drawing equivalencies is almost insulting to the work of masters like Miyazaki. Japanese animation owes more to Japanese filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa and 1000-year old traditions of calligraphic line-work and pictorial scrolls than to The Land Before Time parts 1-14 or Cinderella 3: A Twist in Time.

Studio Ghibli was the greatest studio to emerge from the post-war era (Miyazaki was born during WWII) and counts the only non-English-speaking animated film to win an Academy Award (Spirited Away, 2003). It also released my pick for #1 children’s movie of all time: My Neighbor Totoro (required viewing for all children under the age of 13 and all parents of said children).

Text and Subtext

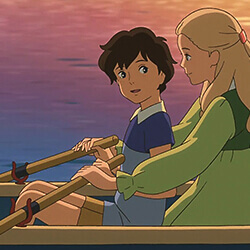

2016 Oscar-nominee When Marnie Was There is the final Ghibli film to be released during Miyazaki’s tenure. It was not directed by him, but it was hand-picked by him for adaptation. While the animation doesn’t compare to Spirited Away, this is from the same team that designed Arrietty (director Hiromasa Yonebayashi), so it is still richer than anything U.S. studios have put out in the last decade. It is a beautiful film full of the kind of lovingly hand-animated goodness fans have come to expect. It’s not a step down from Miyazaki’s work, maybe more of a step-sideways as younger directors with different sensibilities take the reins.

Marnie fits many of the themes we’ve come to expect from Studio Ghibli: A strong-willed girl as lead, other-ness, close connection to the natural world, liminality, magical realism and a hybrid of Japanese and European visual elements. The story follows Anna, an emotionally complex young girl sent to live in a country village by her foster parents. She’s shadowed by tragedy and has a hard time fitting in anywhere. One day as she’s exploring the marshy coast, she comes across an empty mansion. During low tide Anna makes her way to the house and catches a glimpse of a mysterious girl (Marnie) who seems to live in the house. When night falls Anna and Marnie meet, and the house comes to life. They become close friends, though neither they (nor we) quite understand how they are meeting. Some supernatural barrier seems to be crossed each time (Is Marnie a ghost? Is Anna time-traveling? Are they both dreaming?).

The story, based on a British children’s novel written in the 60s, is a meditation on memory, loss, and most of all relationships. Anna is presented as damaged at best and a bully at worst. She pushes everyone away, from her adopted mother to her aunt and uncle to the kids she meets in the village. Her emotional state is part callous pre-teen and part shell-shocked child. Until Anna meets Marnie she seems headed for a breakdown.

The story, based on a British children’s novel written in the 60s, is a meditation on memory, loss, and most of all relationships. Anna is presented as damaged at best and a bully at worst. She pushes everyone away, from her adopted mother to her aunt and uncle to the kids she meets in the village. Her emotional state is part callous pre-teen and part shell-shocked child. Until Anna meets Marnie she seems headed for a breakdown.

Interestingly some U.S. critics found Anna and Marnie’s story to be heavy with sexual subtext (Anna’s same-sex sexual awakening in particular), though the ending rules this out. It is a love story between two young girls, but it’s love is much deeper than the kind of intimacy we’re groomed to expect by our hypersexual culture. When Marnie tells Anna she “loves her more than any other girl” she means it, and we later discover why. Understanding broader themes about the longing for non-sexual intimacy throughout Ghibli’s canon (these are family films after all) as well as the lack of physical intimacy in Japanese culture help give context to the relationship. In the American mind it is difficult to imagine intimacy divorced from sex (in fact the reverse seems to be more common), but that shouldn’t make the twist at the heart of Marnie’s mystery any less poignant.

As Anna and Marnie connect to each other in their magical world, Anna’s defenses start to fall. Her connection to this world becomes brighter and her anger, sadness, and distrust are turned to joy. With its themes of grief, love, and how we affect each other’s lives When Marnie Was There is a romance for children and parents alike. It’s not quite the final love letter from Miyazaki we may have hoped for, but it’s a strong edition to the Ghibli canon. (*Also it won’t win the Oscar)