I wasn’t sure about writing this review until reading a back issue of Film Comment wherein Joan Rivers listed it as one of her guilty pleasures. Please don’t ask for an explanation of that, as I’m not a fan of Joan Rivers, and there is nothing about which to feel guilty in liking The Trouble with Angels. And yet I have, and do. I could blame it on my perfectionism, as the film has a number of weaknesses, but in all honesty, the guilt about returning to The Trouble with Angels again and again might be its sincerity, reverence, and hope, qualities that we all appreciate personally but seem unable to culturally.

Compounding that is most critics’ classification of the film as a phenomenon in director Ida Lupino’s work, which Carrie Rickey characterizes as “a dimly lit, low-budget world where everyone lives sadder-but-wiser ever after.”* Lupino’s noir of the ‘40s and ‘50s was progressive — as it pursued the truth within the taboo — but she was resolved to do so “in good taste” with compassion for the “poor, bewildered people” who comprise humanity.** With the new values of the ‘60s, one would expect Lupino to find projects that aligned with her social convictions, but as Hollywood conflated liberation and hedonism, there were very few scripts offered she was willing to direct. The Trouble with Angels was the only one.

Life with Mother Superior

The plot, or, more accurately, sequence of disconnected scenes, follows friends and troublemakers Mary Clancy (Hayley Mills) and Rachel Devery (June Harding), through their high school years at St. Francis Academy. “The only difference between this place and a girls’ reformatory,” hisses Mary, “is the tuition.” Mary is a bit biased, of course, as her determination to bring chaos to the order exasperates the sisters and Mother Superior (Rosalind Russell). While the story may be “framed within the perennial clash between the noncomformist and the traditionalist,”*** the inevitable and surprising truth of the film, and religion, is that noncomformity is a tradition and the traditional were once noncomforming.

The Trouble with Angels draws from Life with Mother Superior by Jane Trahey, and at the author’s own admission, it “relates more to the frosting than the cake.” Don’t misunderstand, I have no desire to grow out — or get rid — of frosting. But the cake is important, too, and mostly missing from the book. Blanche Halanis’ adaptation keeps the best jokes, installs a character arc and patches some holes, but one of the biggest blessings is Jerry Goldsmith’s score, sustaining the film through its fits and starts, the tone effortlessly and memorably scaling from absurd to sublime and plenty in between. “Lupino knew she could not give Trouble classic narrative form,” writes Bernard F. Dick, “but she could establish a rhythm that would give it the equivalent.” An intermittent vehicle, yes, but one this team of artists learned how to drive.

The Trouble with Angels draws from Life with Mother Superior by Jane Trahey, and at the author’s own admission, it “relates more to the frosting than the cake.” Don’t misunderstand, I have no desire to grow out — or get rid — of frosting. But the cake is important, too, and mostly missing from the book. Blanche Halanis’ adaptation keeps the best jokes, installs a character arc and patches some holes, but one of the biggest blessings is Jerry Goldsmith’s score, sustaining the film through its fits and starts, the tone effortlessly and memorably scaling from absurd to sublime and plenty in between. “Lupino knew she could not give Trouble classic narrative form,” writes Bernard F. Dick, “but she could establish a rhythm that would give it the equivalent.” An intermittent vehicle, yes, but one this team of artists learned how to drive.

Transfiguring Effect

“I did not set out to be a director,” Ida Lupino recalls. “We had this wonderful old-time director, Elmer Clifton, [but] about three days into the shooting of Not Wanted [her production company’s debut film], he got heart trouble. Since we were using my version of the script, I had to take over.”**** This was Lupino’s first day on the job, and it wouldn’t be her last. The independent company she formed with two other collaborators — The Filmakers — was already an extraordinary accomplishment for the time, but their projects were even more so, centering on women and the struggles that society could not understand nor forgive: pregnancy out of wedlock, the repercussions of rape and bigamy.

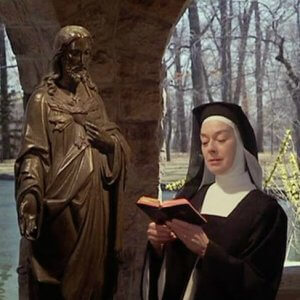

“One problem in evaluating the significance of these characterizations,” writes Dan Georgakas, “is that today they seem humdrum.”***** By contrast, The Trouble with Angels almost appears revolutionary: an unambiguously genuine and affectionately funny film about the beauty of the religious life. A beauty that is natural and supernatural. “[Lupino] sensed the spiritual aura of [the location]…interspersed throughout the film [are] scenes in which the camera roamed the grounds like a first-time visitor, stopping occasionally at a pond adorned with water lilies or at a statue of a saint, until another episode [is] ready to unfold. Once Lupino realized the transfiguring effect the nun’s habit had on Rosalind [Russell], who seemed born to it, shots of Reverend Mother became iconic images.”******

Deep Spirituality

Russell was reverent herself, a devout Catholic who took pains, while photographed in her habit, to never have a cigarette or cocktail in hand. Perhaps she was honoring the memory of the nuns that taught her from grade school through college; as a biographer writes, “their ways were hers — a deep spirituality often masked by a façade that suggested otherwise.”*******

Such a façade is beneficial when starring in comedies, where Russell belonged, with her almost mechanical instincts for language, expression, and timing that rival any of the greats in her era. However, at the right moment, she could let that façade slip, exposing profound feeling. Trouble gives her several opportunities, particularly a monologue in which Mother Superior remembers leaving her possible career to become a nun. Grace abounds here, from Halanis’ script, and Russell’s performance; instead of perpetuating the false dichotomy of secular and spiritual, they portray the good and the “something better,” not a universal standard, but a vocation found through experience and contemplation, personal to Mother Superior.

Such a façade is beneficial when starring in comedies, where Russell belonged, with her almost mechanical instincts for language, expression, and timing that rival any of the greats in her era. However, at the right moment, she could let that façade slip, exposing profound feeling. Trouble gives her several opportunities, particularly a monologue in which Mother Superior remembers leaving her possible career to become a nun. Grace abounds here, from Halanis’ script, and Russell’s performance; instead of perpetuating the false dichotomy of secular and spiritual, they portray the good and the “something better,” not a universal standard, but a vocation found through experience and contemplation, personal to Mother Superior.

Mirror Images

“As mirror images, Reverend Mother and Mary are fascinated by each other…they have a common bond: pride.”******** This battle of the wills is why we keep watching, wondering who will surrender, although it wouldn’t be so without the performance of both Russell and Mills. Life imitated art in that the two were never friendly; the former made a sincere effort at first and the latter made faces when her back was turned.

Thankfully this translates to their interactions onscreen, animating the mutual resentment. But Russell spoke well of Mills’ talent, and indeed, she has a maturity and wit, most charming when it contrasts with her youth — in Pollyanna, The Parent Trap, and The Trouble with Angels.

In that list, the difference between the first two films and the last is, perhaps, a point of view. Lupino believed the entertainment industry had a public duty, claiming that “movies and television stories should be…stories about people done in good taste.” She was not advocating for the oversimplification of morality, but a responsible presentation of reality. And the reality is, sometimes people choose rightly, enter through the narrow gate, and find something better.

__________________________________________

*From “The resurrection of Ida Lupino” by Susan Fegley Osmond. World & I, March of 1998, Vol. 13, Issue 3

**”Resurrection,” Osmond.

***Forever Mame: The Life of Rosalind Russell by Bernard F. Dick. University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

****Making Waves: The 50 Greatest Women in Radio and Television / as selected by American Women in Radio and Television, Inc. Edited by Jacci Duncan. Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2001.

*****”Ida Lupino: Doing It Her Way.” By Dan Georgakas. Cineaste, 2000, Vol. 25, Issue 3

******Forever, Dick.

*******Ida Lupino: a Biography by William Donati. University Press of Kentucky, 1996.

********Forever, Dick.