Holiday movies are often based around the importance of family and the simple truth that family is often more dysfunctional than we’d like. Consider A Christmas Story or It’s a Wonderful Life and the discontent drawn from family relationships therein. Or if you prefer, look no further than a more modern offering such as Christmas with the Kranks, where family quirks are drawn to their extremes for the purpose of getting a laugh or even a half-earned tear or two. Of course, the idea is that all families are dysfunctional, and it’s interesting to see characters who look like us on the silver screen.

But film does operate in a separate sphere than other mediums, where we’re asked to suspend our disbelief just a little more than usual. It’s why we don’t question the absurdity of Elf, but get a little bored with the drama of something like The Family Stone. Yes, we want to see other families like ours, bickering and snippy, around the holidays. But it’s also nice to know we might be a little more normal than the characters on our TV.

Netflix’s The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), is not a Christmas movie, admittedly. But it does draw on similar themes of missed connections and family dysfunction to earn its laughs and, possibly, tears. And unlike many family dramedies of modern Hollywood, it wisely ups the ante by focusing on the absurdities a touch more than a real family actually would.

Harold Meyerowitz: Artist

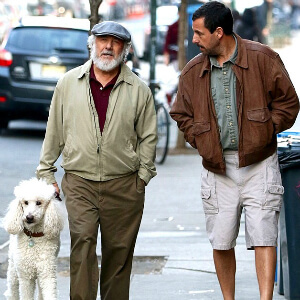

Consider, first, the relationship between Harold Meyerowitz (Dustin Hoffman) and his sons, Danny and Matthew (Adam Sandler and Ben Stiller.) The patriarch is a forgotten — if he were ever truly remembered — artist and professor, whiling away in his eccentric home with his alcoholic wife (Emma Thompson), when Danny decides to move in after he and his wife divorce. Danny has no tools of any trade, other than being a mediocre city driver and kitschy songwriter. His father doesn’t make things any easier, subtly projecting his career missteps and failures onto his eldest son. Meanwhile, he boasts proudly of Danny’s half-brother, Matthew, a successful businessman and seemingly failed Meyerowitz… at least in the sense that he’s no artist.

Harold’s contrasting relationship with the two is the focal point of the film, blurring lines between his two different parenting styles with each. He treats one like a friend and the other like a disappointing piece of his own creation, all while the two separately try to reconcile their different lives with the one thing they have in common: Harold. Their sister, Jean (Elizabeth Marvel), also cuts in, an example of life as a Meyerowitz woman. Jean’s is the saddest story of the 3 in that it’s so cut short, not so much a narrative oversight as a reflection on the failures of a father to see and appreciate his own daughter.

Harold’s contrasting relationship with the two is the focal point of the film, blurring lines between his two different parenting styles with each. He treats one like a friend and the other like a disappointing piece of his own creation, all while the two separately try to reconcile their different lives with the one thing they have in common: Harold. Their sister, Jean (Elizabeth Marvel), also cuts in, an example of life as a Meyerowitz woman. Jean’s is the saddest story of the 3 in that it’s so cut short, not so much a narrative oversight as a reflection on the failures of a father to see and appreciate his own daughter.

Noah Baumbach, the film’s writer and director, wisely portrays the Meyerowitz children less as people than as works of art. They’re messy and incomplete, and much like Harold’s art, it’s hard to decipher whether they’re good or bad. Instead, they operate in a fluctuating state of change, even well into their lives.

Dawn Meyerowitz: Father

Harold’s parenting is directly drawn against Danny’s relationship with his daughter, Eliza (Grace Van Patten). While Harold’s affection could most generously be categorized as “at times, accidental,” Danny dotes on his “genius girl.” And it shows. Eliza seems enriched in her relationships and school work — oddly avant-garde as it may be — mostly because of the support of her father. She eagerly sends him all her movies and he watches along, almost always confused, yet always insisting the latest is her best yet. Meanwhile, she treats almost everyone with an effortless kindness, something her father passes along without getting it from the family patriarch himself.

Harold’s and Danny’s relationship is probably the most essential in the film, though we’ll get to that of Danny and Matthew in just a second. It’s a traditional formula, that of “the parent who learns from the failures of their parents,” but Baumbach does a good job of making it feel fresh this time around, if mostly because the two performances are so straightforward.

Harold’s and Danny’s relationship is probably the most essential in the film, though we’ll get to that of Danny and Matthew in just a second. It’s a traditional formula, that of “the parent who learns from the failures of their parents,” but Baumbach does a good job of making it feel fresh this time around, if mostly because the two performances are so straightforward.

Dustin Hoffman acts as any older, experienced artist would, speaking mostly in subtext while vaguely hinting at his affection for those around him. However, there’s a twinge of committed sadness to him, almost as if he refuses to acknowledge his own failures out of the fear they’ll kill him. On the other hand, Sandler’s Danny wears his heart on his sleeve, the emotional, sometimes fragile son who gives everything to those around him without the slightest regard of where it leaves him. One is so obtuse and the other so transparent, it’s easy to forget how guarded both of them are.

Danny and Matthew Meyerowitz: Siblings, Rivals

There’s little interest in drawing Sandler and Stiller’s half-brother characters as rivals, though that’s the initial picture we get. The focus seems to be on how the two are at war with their differing versions of the same father: one who seemingly let his children be their own people; the other instilling care and attention on his protege.

Framing the character’s continued interaction around a planned art showing and an unplanned sickness, Baumbach does an effective job of showing us what each man really wants, from their father and from each other. There’s less of a light bulb moment in the end, and more of a steady realization of things the brothers already know about themselves. And by the film’s conclusion, there’s a cathartic acceptance of who they are and who they want to become. Both character arcs rival lifelike change, while still capitalizing on the ticks that make each character absurd enough to fit in the movie’s reality.

It’s long been my opinion that Ben Stiller is one of Hollywood’s quiet geniuses. For every Zoolander or Meet the Fockers, there’s a Tropic Thunder or Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Stiller is up to the task here, his inevitable charm cut with a nice amount of detachment. But the real story of Meyerowitz is Adam Sandler. Since signing his mutli-flick deal with Netflix, Sandler has continued his punchline run as one of America’s premiere “Him again?” artists. But stripped of seemingly endless creative control, Sandler is actually freed to do some excellent work here, especially when playing off of Hoffman and Stiller. There’s a beautiful sadness to his work here, echoed probably only in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch Drunk Love. And while Sandler’s comedic penchants are still here — shouting, singing, slapstick — they’re much more effective in the context of Danny’s character, equal parts father and son trying to learn his role in a new stage of life.

It’s long been my opinion that Ben Stiller is one of Hollywood’s quiet geniuses. For every Zoolander or Meet the Fockers, there’s a Tropic Thunder or Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Stiller is up to the task here, his inevitable charm cut with a nice amount of detachment. But the real story of Meyerowitz is Adam Sandler. Since signing his mutli-flick deal with Netflix, Sandler has continued his punchline run as one of America’s premiere “Him again?” artists. But stripped of seemingly endless creative control, Sandler is actually freed to do some excellent work here, especially when playing off of Hoffman and Stiller. There’s a beautiful sadness to his work here, echoed probably only in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch Drunk Love. And while Sandler’s comedic penchants are still here — shouting, singing, slapstick — they’re much more effective in the context of Danny’s character, equal parts father and son trying to learn his role in a new stage of life.

The Meyerowitz Stories, Same as They Ever Were

Family dysfunction and holiday movies go together like milk and cookies, an easy formula guaranteed to please at a time of year when we find ourselves surrounded by the people who share our blood. Again, The Meyerowitz Stories isn’t a holiday film — not even in the questionable realm of Die Hard or Just Friends — but it still actively functions in the same areas.

But one of the things family dysfunction flicks never seem to get right is the acceptance of each other. Sure, there might be a few hokey monologues with the subtext of, “Why can’t we all just love each other?” But ultimately, the resolution in these movies is predicated on change as a qualifier of love. The underlying truth: family love is good, but unnecessary in the face of stubbornness and refusal to change. Maybe, in this age of American hyperpartisanship, this message will begin to seem more relevant.

But it seems like Meyerowitz captures an unspoken truth at the heart of the family dynamic: change won’t always happen like you want, if it ever does in the first place. And instead of waiting for the changes you want to see in your loved ones, maybe it would better to choose another path. In his letter to Colossae, Paul encourages them to put on, “compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience.” It’s followed by the simple command of “forgive each other.”

By the end of The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) there’s little evidence of change. Everyone’s dynamics are (largely) the same, save some lifestyle changes. But there seems to be more willingness to make space for each other amongst the chaos of life. Maybe that’s something we should all remember come Christmas time.