What if Bob Dylan had never sold a record? Imagine that.

Imagine that none of us have ever listened to one of America’s greatest singer-songwriters. What if one our most iconic musicians had cut two albums — just two — but we’ve never heard the songs; we’ve never heard “Mr. Tambourine Man” or “Like A Rolling Stone” or “Watchtower” or “Tangled Up in Blue”? Try to picture an America where no one in 60s counter-culture had ever heard “The Times They Are a-Changin,” because maybe Dylan had to hang it up early because his albums just didn’t sell, so he had to be realistic and work a construction job to provide for his family. And maybe way back in the day you actually worked with Dylan — think of that — but instead of being an icon, he was just “Bob” to you, one of the guys, and that was a long time ago. He used to play music, you recall, he mentioned that, but you actually never heard Bob play, come to think about it. Then one day you discover that those two albums he cut all those decades back are super sensations overseas and that they’ve helped to inspire a resistance to totalitarian rule in a land far away.

The Day the Music Died

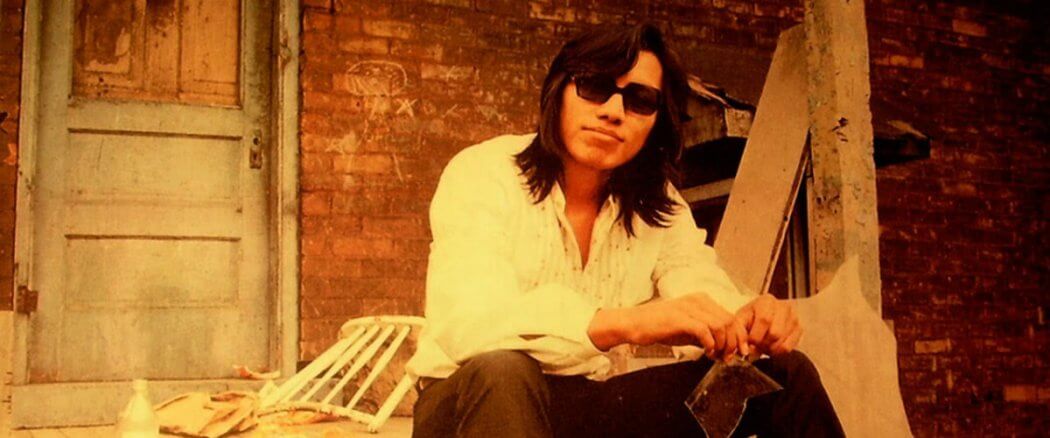

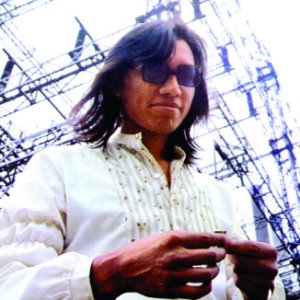

This is the story told in Searching for Sugar Man, only it isn’t Bob Dylan, it’s a musician you likely haven’t heard of, Sixto Rodriguez, a Detroit native familiar with the streets and back alleys, who played “hooker bars…and halfway houses…” as he put it in a tune from his second album Coming From Reality. I hadn’t heard of Rodriguez, myself, until a few years back when I was traveling in South Africa. Like most Americans, prior to the release of the Searching for Sugar Man documentary, I hadn’t listened to the sounds of a musician whose songs are every bit the caliber of Dylan.

I was riding in a car with Kim, a friend in Cape Town, enjoying the beauty of the Western Cape, the rolling hills, the summer sun, and the wind blowing in from the sea. For me, the tranquility of these moments contrasted sharply with the history of violence and oppression in South Africa, with these effects continuing to shape the present.

Kim played Rodriguez for me, with no explanation and no back story, and asked me if I liked the music. I told her that I loved it, really loved it. It was speaking to me, although I didn’t really understand at the time, there was something about the sound that seemed to make sense of much of the senselessness of colonialism and imperialism that had broken my heart and that I had been trying to come to grips with after 7 months in Africa.

Kim played Rodriguez for me, with no explanation and no back story, and asked me if I liked the music. I told her that I loved it, really loved it. It was speaking to me, although I didn’t really understand at the time, there was something about the sound that seemed to make sense of much of the senselessness of colonialism and imperialism that had broken my heart and that I had been trying to come to grips with after 7 months in Africa.

Kim nodded with appreciation. “We South Africans are quite keen on his music,” she said with a sideways glance that told me there was a story.

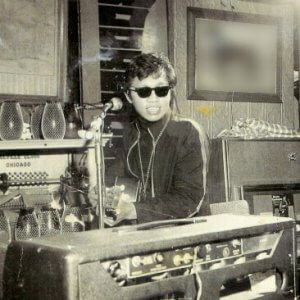

It’s a story that Swedish filmmaker Malik Bendjelloul tells so beautifully in his 2012 documentary. The film begins in Detroit, dark and grim. Amidst the struggle and poverty of The Motor City, there is a songwriter, shy and reserved on stage, with long, dark hair. To the professionals who discover him, his talent is unquestioned, and eventually an album is released, followed by another a year later.

We hear interviews with the producers and music critics. This is an artist with real genius, and the album receives critical acclaim. Everything is on track for success, it seems, except for the fact that the album doesn’t sell. It is a complete commercial flop.

And that’s it. The curtain closes on the aspirations of this gifted artist.

The Dylan of South Africa

Then the film shifts to South Africa. Here in South Africa, they say, Rodriguez was on par with the Beatles. This isn’t an exaggeration. His songs were everywhere. Thumb through a record collection in South Africa a few decades back, and you would always find a Rodriguez album. Someone estimates that half a million copies sold, all told. In South Africa, it wasn’t Bob Dylan, it was Rodriguez. Yet the man himself never knew. In the pre-Internet era, Rodriguez was unaware that his albums were Gold.

This was Apartheid South Africa, a repressed society under a totalitarian white, racist regime. Any hint of liberalism was censored; any art that challenged the “Christian” values of the conservative white ruling class was banned. The film takes us into the archives from decades gone by and we see the records themselves and the rings with scratches on songs that were not approved, scratched out to ensure they would not be played on the radio stations that were all controlled by the ruling Party.

This was Apartheid South Africa, a repressed society under a totalitarian white, racist regime. Any hint of liberalism was censored; any art that challenged the “Christian” values of the conservative white ruling class was banned. The film takes us into the archives from decades gone by and we see the records themselves and the rings with scratches on songs that were not approved, scratched out to ensure they would not be played on the radio stations that were all controlled by the ruling Party.

Nonetheless, the music couldn’t be stopped, and even the banned songs made their way around the nation, and white musicians and artists were inspired by the music of Rodriguez, energized to push back against the repression of their society and the misery of Apartheid. From the streets of Detroit, to the heart of one of the most oppressive cultures in recent modern history, the music taps into something universal.

The film itself doesn’t explore this connection in depth, but the link provides much food for thought for those of us inspired by the Gospel that Jesus proclaimed when he said, not without irony, “Blessed are the poor, for theirs is the Kingdom of God.”

The Poet-Prophet

After listening to Rodriguez as much as I have, I can’t help but listening to his music in light of the influence he had on South Africa, as though it were written for South Africa. Like Dylan, Rodriguez was a masterful lyricist with the ability to merge empathy and truth-telling, that knack for just the right turn-of-phrase that illuminates the spirit of the age, the gift of a true poet-prophet. Somehow Rodriguez’s music juxtaposes sounds that are sympathetic and serene alongside truth-telling lyrics. The music isn’t necessarily drumming for violent revolution or hammering for revolt, but it comes from the streets, birthed from the struggle, and yet there is real tenderness and sensitivity in his songs. They challenge the establishment and yet manage at the same time to be soothing and even therapeutic.

Both Detroit and South Africa are seats of suffering, they are both at the heart of the wreckage of American capitalism on the one hand and European colonialism on the other — oppression and exploitation by different names and by different means. The universality of Rodriguez spoke to the people of South Africa, an ocean away.

Both Detroit and South Africa are seats of suffering, they are both at the heart of the wreckage of American capitalism on the one hand and European colonialism on the other — oppression and exploitation by different names and by different means. The universality of Rodriguez spoke to the people of South Africa, an ocean away.

Meanwhile, in the United States, no one had heard of Rodriguez, this Bob Dylan of South Africa whose music was helping to change a nation. In the film we hear from the children of Rodriguez, and even they had no idea. Ditto with the executive of the record company in the United States who allegedly received royalties and gets heated as he denies that there were any royalties or that he knew anything at all. As for Rodriguez, himself, after his two albums were released in 1970 and 1971, he worked manual labor jobs to provide for his family and make ends meet. A prophet, Jesus said, is not without honor except in his own town.

Yet even this is not the whole story of Searching for Sugar Man. As incredible as all this is, the tale told gets weirder and stranger, with one wallop of a twist at the end. The documentary is a startling search for Sugar Man by South African sleuths and music aficionados across the ocean, and it’s a journey for Americans to discover one of their own greats, hidden in plain sight.

From start to finish, I found this to be one of the most remarkable and inspiring documentaries I’ve ever seen, produced with a care and concern reflective of the music of Rodriguez himself. Fittingly, the artistry and sensitivity of Searching for Sugar Man won an Academy Award for Best Documentary. Rodriguez wasn’t there, but through the exposure of the film, his music and influence continues.