“We’re all the children of God,” a black sophisticate remarks to her boyfriend, after he has interacted with the police. “Forget it.” The exchange is brief — the actor isn’t even credited — but her sharp delivery slices right through a thick curtain of denial that’s always hanging around; the hypocrisy of a United Kingdom declaring “the inherent dignity [and] equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”*

“We plan to show this prejudice as the stupid and illogical thing it is,”** announced director Basil Dearden, during the filming of Sapphire. That’s a clear purpose, one guided by Janet Green’s candid script. But then, the director and writer were white, so to be angry — to express that anger — to be given the means of transmuting that expression — was a route available to them, not others, even though others had a more urgent and personal need to access it. The inequity was, and is, wrong. It also emphasizes the importance of stewardship, or leveraging privilege. Sapphire takes its opportunity with care, intensifying through precision and detail, picking at the lock on this chain of injustice, made through activity and complicity.

Which Way It’s Going to Go

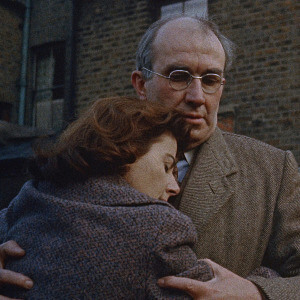

“This girl was killed in hate, not fear,” Superintendent Hazard (Nigel Patrick) remarks to Inspector Learoyd (Michael Craig), about the murder of Sapphire Robbins (Yvonne Buckingham) that opens the film: a beautiful girl with light skin and red hair, stabbed nine times. “This [murderer] went on and on, ‘til he was exhausted.”

“Who’d do such a thing?” Friends ask, but as the investigation begins, the more pressing question is, who was Sapphire? A locked drawer is discovered, filled with flamboyant outfits no one saw her wear. We learn both parents are dead and she wanted “to be counted in, to belong.” There is another relative, Sapphire’s brother, who doesn’t appear until the 13 minute mark, accompanied by a flare of the jazz score: Dr. Robbins (Earl Cameron), respectful, controlled, loyal — and black.

“Who’d do such a thing?” Friends ask, but as the investigation begins, the more pressing question is, who was Sapphire? A locked drawer is discovered, filled with flamboyant outfits no one saw her wear. We learn both parents are dead and she wanted “to be counted in, to belong.” There is another relative, Sapphire’s brother, who doesn’t appear until the 13 minute mark, accompanied by a flare of the jazz score: Dr. Robbins (Earl Cameron), respectful, controlled, loyal — and black.

Startled, Hazard asks a few other questions, then the one we’re all thinking. “Are you — were you — Sapphire’s half-brother?” Dr. Robbins replies, “No. Our father was a doctor, white, our mother, singer, black as iron,” he almost smiles. “You never know which way it’s going to go.” It’s a wry comment, dense with meaning, for both the character and the story. Through interviews and evidence, we quickly learn that Sapphire had committed to an imitation of life, disassociating from black friends and spaces, passing for white. It’s the first twist in a screwy case.

Keep Britain White

Shortly after the Second World War ended and a reconstruction plan for the British economy had been developed, The Royal Commission on Population proclaimed that immigrants of “good stock” would be welcomed “without reserve.” Although this welcome was intended for white Europeans, it attracted other workers from the Caribbean, India, and Pakistan. Many immigrants found a home in Notting Hill, which, at the time, was composed of former estates that had been split into multiple occupancies.***

But their arrival was resented by white, working-class young men and far-right groups. Years of coiling hostility sprung into the riot of 1958, lasting weeks and shocking the nation. “In one street where some of the ugliest fighting has taken place,” wrote The Times, “your correspondent found a group of men in a public house singing ‘Ol’ Man River’ and ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’ and punctuating the songs with vicious anti-Negro slogans. The men said that their motto was ‘Keep Britain White.’”****

Undermine It With Truth

Janet Green was ready to fight back — or rather, write back. Under contract with the Rank organization, a legendary entertainment conglomerate, Green had built a career on the police procedural, having written multiple scripts with an investigation at the center. Sapphire is both the result of her style and a response to the riot. It presents an impressive range of perspectives, while maintaining a moral center and encouraging commentary to occur naturally, through the comments of its characters. Despite the skill and power of the piece, at the time, there were very few established directors brave enough to accept it. One of them was Basil Dearden.

I was a fan of Dearden before I knew who he was. “Given his strikingly eclectic body of work, it’s not surprising that Basil Dearden has never become a household name,” writes Michael Koresky. “He’s too hard to pin down.” It’s true. The films directed by Dearden I saw prior to this one — Dead of Night (1945) and Victim (1961) — are not just different material; they seem sewn by a different hand. And in the ‘50s and ‘60s, he had a hand in stuff that most filmmakers weren’t willing to touch: racism, homophobia, middle-class discontent. These weren’t simply iconoclastic or sensationalist choices. Dearden didn’t understand the hatred around him and sought to undermine it with truth.

I was a fan of Dearden before I knew who he was. “Given his strikingly eclectic body of work, it’s not surprising that Basil Dearden has never become a household name,” writes Michael Koresky. “He’s too hard to pin down.” It’s true. The films directed by Dearden I saw prior to this one — Dead of Night (1945) and Victim (1961) — are not just different material; they seem sewn by a different hand. And in the ‘50s and ‘60s, he had a hand in stuff that most filmmakers weren’t willing to touch: racism, homophobia, middle-class discontent. These weren’t simply iconoclastic or sensationalist choices. Dearden didn’t understand the hatred around him and sought to undermine it with truth.

Places Many Had Never Been

In Sapphire, Dearden relies upon the rhythm of the script and of life: emotions are truncated and concealed, drab exteriors surround plain interiors, light borders shadow; all ordinary, all drawing us closer and closer to the people. Of course, the people wouldn’t be very interesting without capable actors, and the cast is more than that, particularly Gordon Heath, who has one of the best scenes and doesn’t miss a single beat of it; and Yvonne Mitchell, who has the other best scene and rends it to bits.

The few stylistic flourishes in the film — its opening sequence, a chase scene, the disproportionate temper of policemen in interrogation, the jazz score — are almost always used to represent the extraordinary danger of being black. But Sapphire’s tone is measured, even cool at times, which both belies its immediate impact and rewards repeat viewings. “If the film seems less than radical now, it’s worth noting that British cinema reverted to being exclusively white for some time afterward,” writes Koresky. “Dearden had taken viewers places many had never been.”

The truth is neither Dearden nor Green should have been the chosen ones for taking viewers to these places. It should have been a team of black filmmakers. But if that had been the team, it’s unlikely the film would have happened. Green seemed to intuit this tension — between the individual, the system, our choices and those made for us — in a line she gave to Dr. Robbins: “I’ve seen all kinds of sickness in my practice. I’ve never yet seen the kind you can cure in a day.”

__________________________________________

*From “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” the United Nations, 1948.

**This, and all Michael Koresky quotes, are from his superb article for Criterion Collection’s package set of Dearden films.

***“A History of Citizenship: Brave New World,” The National Archives.

****“White Riot: The Week Notting Hill Exploded,” Mark Olden, The Independent, August 29th, 2008.