Deadlines. Creativity. Beauty. Truth. None of these are grammatically correct sentences. I can tell because of the green squiggling line underneath that short section in my Word document. The importance is the emphasis of separating these words from the traditional Subject-Verb-Object structure and leaving them to stand alone as complete ideas. This hints at something of their quintessence. Something people who deal with these concepts on a regular basis understand. People who do not understand are made to understand that they are significant – how could they not be, they stand alone, whole and complete (but not really, they more hint at the idea of being complete via the unspoken — it’s a kind of grammatical dark matter).

Maybe this introduction (that seems, and mostly is unrelated) is moving beyond the point of having a point relating to anything to do with the film… but in a way that is the film, and its point: wrestling with the issue of balancing self-indulgence while trying to say something new and important that you’re unsure how to articulate.

A Movie About a Movie

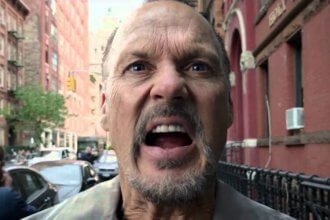

Adaptation is the story of trying to write a screenplay that encapsulates this concept… how do you write a movie that gets at something simple and beautiful and non-narrative driven as flowers? In short – you don’t, you write a movie about trying to do this, failing, and succumbing to the cliché… all while maintaining enough self-awareness to create something both genuine (despite the neuroses) and incredibly funny. Not funny in the tear inducing sense, but more in the realm of an elaborate joke that builds upon itself until it finally culminates in certain moments and you smile, or chuckle, or scoff even.

All of these characteristics are common in the post-modern metafiction (or metafilm in this case). Self-awareness, cynicism (but the kind where you still secretly hope for happiness rather than falling into the black modernist despair [at least I feel there is ample evidence to support this opinion, because it’s not technically an actual component]), a very internalized and impressionistic vision, discomfort & awkwardness rather than the sharp and crisp dialogue of yore, and an alarming honesty (what screenwriter would write about themselves fantasizing about the author of the book they are adapting?), and the types of jokes that require knowledge of all the people involved, e.g. Donald Kaufman (Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s twin brother in the film), yeah, he’s not real… completely made up, and watching it under that context makes several scenes incredibly funny, because he is everything his brother isn’t and hates, but kind of secretly wants.

All of these characteristics are common in the post-modern metafiction (or metafilm in this case). Self-awareness, cynicism (but the kind where you still secretly hope for happiness rather than falling into the black modernist despair [at least I feel there is ample evidence to support this opinion, because it’s not technically an actual component]), a very internalized and impressionistic vision, discomfort & awkwardness rather than the sharp and crisp dialogue of yore, and an alarming honesty (what screenwriter would write about themselves fantasizing about the author of the book they are adapting?), and the types of jokes that require knowledge of all the people involved, e.g. Donald Kaufman (Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s twin brother in the film), yeah, he’s not real… completely made up, and watching it under that context makes several scenes incredibly funny, because he is everything his brother isn’t and hates, but kind of secretly wants.

Creative Process and Neuroses

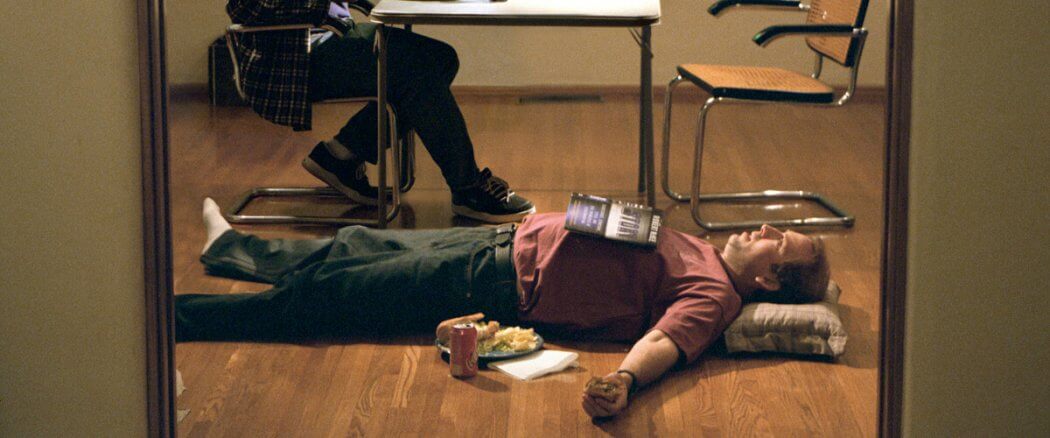

Anyone who has ever attempted to create something knows the self-consuming process – the balance between self-indulgence and writing to an audience, the bursts of insight that leave you in a state of uncertainty, i.e. should I just toss this project and start over? The Ouroborus reference hits at the peak of this self-consuming portion of the script – right after it has lost all relation to the book that is being adapted and we are trapped with Charlie Kaufman in never ending loops of speaking into his recorder about scenes we have already watched only to be interrupted at the height of ecstatic breakthrough by Donald. It’s even Donald who mentions the snake, and his not knowing the name of the snake adds to Charlie’s disgust (he already loathes his brother’s success with women, his willingness to write formulaic scripts and learn how to write them from Robert McKee’s Screenwriters’ Workshop).

Dorothy Sayers, in her book Mind of the Maker, pieced together an insightful premise on creativity: as we are of God’s nature, and his first act (that we are made aware of) is creation, it naturally follows that we are creative. It is in our essence as God’s image bearers. The only problem is that everything He created is “good,” us… not so much. And this is the struggle the film follows. Even though it is “based” off of a book, the movie itself is really about that creative process of taking and reflecting the beauty we see, of being true and honest to it; and how in this process we sometimes stumble onto something else entirely. More often than not we depict a world revolving around ourselves. More often than not we live in a world we cannot understand unless we perceive it as revolving around ourselves. If there is a turn for the moral in Adaptation, this is it: The plot moves out of stagnancy when Charlie looks beyond himself and into the world of others.

Fidelity…But to What?

Fidelity comes from Latin, fidelis, and at the root of it is faithfulness, an unflinching and idyllic bond of trust formed through strict promise keeping. This is a significant motif within the film. In Adaptation the idea of fidelity has several layers, and is the basis for most of the film’s conflict. There is an interesting moral question raised on fidelity – which form of it is most important? Is it the fidelity to a faltering marriage, or to the pursuit of romantic ideals beyond? Should one remain faithful in creative transcription, or do you find your own voice within the adaptation… something that moves beyond original intent, and into something more pertinent to you (as the creator – in this case Charlie Kaufman’s concept for a script vs. Susan Orlean’s book from which it is adapted).

At the end of the film we are left wrestling with fidelity’s importance – our faithfulness to other’s expectations of us, our faithfulness to promises and vows (be those deadlines, or a marriage), our faithfulness to honesty, to family (even fake family like Donald), to ourselves, and to the truth as a whole. This is especially difficult to reconcile because the artistic ideal of creating something simple, and true, and not extreme (in terms of standard Hollywood narratives built on lust, betrayal, and violence) that we are presented through the first 90% of the movie seem to be tossed aside at the moment of deadline crisis (which coincides with Kaufman’s personal existential crisis). Then after all of this, there is this odd hope, and not hope in the tangible Christian sense, but in the Naturalist’s sense: Hope! Because… hope!

At the end of the film we are left wrestling with fidelity’s importance – our faithfulness to other’s expectations of us, our faithfulness to promises and vows (be those deadlines, or a marriage), our faithfulness to honesty, to family (even fake family like Donald), to ourselves, and to the truth as a whole. This is especially difficult to reconcile because the artistic ideal of creating something simple, and true, and not extreme (in terms of standard Hollywood narratives built on lust, betrayal, and violence) that we are presented through the first 90% of the movie seem to be tossed aside at the moment of deadline crisis (which coincides with Kaufman’s personal existential crisis). Then after all of this, there is this odd hope, and not hope in the tangible Christian sense, but in the Naturalist’s sense: Hope! Because… hope!

And they do a fantastic job, because you really do feel this sense that “everything’s going to be alright.” It’s easy to stop there and chalk this one up (despite the strange journey you travel to get to this point) as a hopeful movie, but it’s not. A little closer look and you realize that hope is gone once the next deadline comes, and this is just Charlie’s brief reprieve.

So, Why Do I Like This Movie?

Is my sense of humor just warped or something? Possibly, but I think there is more to it than that. This movie is an honest reflection culturally. We probably all know people like this: positive, optimistic, and unable to account for anything in their beliefs about the world that account for these hopeful feelings – or, like Charlie, we probably all know miserable people who want happiness without God, who find it in moments of success, but what is so often lost is that those moments pass, quickly. It seems strange to say, but one of the strongest, most faith building aspects of this film, is the absence of hope through Christ.

Throughout the movie we watch these ideologies unravel – artistic integrity, relationships, status, you name it. The only way Charlie gets any of those things back is by “selling out,” by compromising for the worldly good, rather than standing for the ideals he set forth with. The Christian walk is similar. Our ideology is at conflict with what the world deems worthy of a pat on the back, and because of that we make decisions of fidelity daily. Am I of the world, or am I of Christ? We often mistake the pats on the back for signs of having done the right and best thing. But, just like that moment of hope in the movie, it passes once the next project needs to be undertaken, and like the opening scene where Charlie Kaufman is wandering lost on the set of Being John Malkovich (another script he has penned) and realizes how insignificant he is now that he’s churned out what they wanted, he will return right back into the cycle of Ouroborus. How do we break that cycle?

We don’t. Christ does, and when you watch that cycle unfold Christ’s absence becomes the largest presence.