Welcome to part two of our Oscar picks! Here’s part one if you missed it: Oscars 2018 – Who Should Win? (Part One)

Remember, these aren’t the movies that will win, these are the movies that should win. Here are our picks for the most coveted categories of the night…

Best Supporting Actress

Mary J. Blige — Mudbound

Allison Janney — I, Tonya

Lesley Manville — Phantom Thread

Laurie Metcalf — Lady Bird

Octavia Spencer — The Shape of Water

I like Octavia Spencer, but this is the second year in a row she’s been nominated for a performance that isn’t Oscar-worthy. Last year, Taraji P. Henson was the obvious Oscar pick for Hidden Figures, but she was snubbed and Spencer made the shortlist. This year, Spencer is even more ordinary in The Shape of Water due to an undercooked character arc. Yet she once again secured the nomination. There are a number of roles more deserving of Spencer’s spot. My personal pick? Melissa Leo for Novitiate. Place the two performances side by side and there’s simply no comparison.

If there was an Oscar for Best Stare, Lesley Manville would win hands down for Phantom Thread. But that’s pretty much all she does in the movie. When Vicky Krieps gets angry, Manville gives her the death stare. When Daniel Day-Lewis starts to whine, Manville shoots him a sideways glance so icy it makes his blood run cold. What’s missing is a three-dimensional character. There isn’t enough meat on the bone for Manville to display the depth of her talent, and that makes this nomination a head-scratcher.

One could make the same argument for Mary J. Blige in Mudbound. Her Florence is a mere sketch of a character, but there’s a presence she brings to the film that’s undeniable. Just a close-up of her in sunglasses somehow fills the screen with power. Her words may be few, but she performs from her body. The most powerful moment comes when Florence agrees to leave her family and help take care of her white landlords’ kids. She’s given a choice, but it doesn’t feel like one. Her voiceover puts words to the injustice: “Now I know that love is a kind of survival.” Blige leaves a mark on the film with the smallest share of dialogue in the main cast. That’s talent.

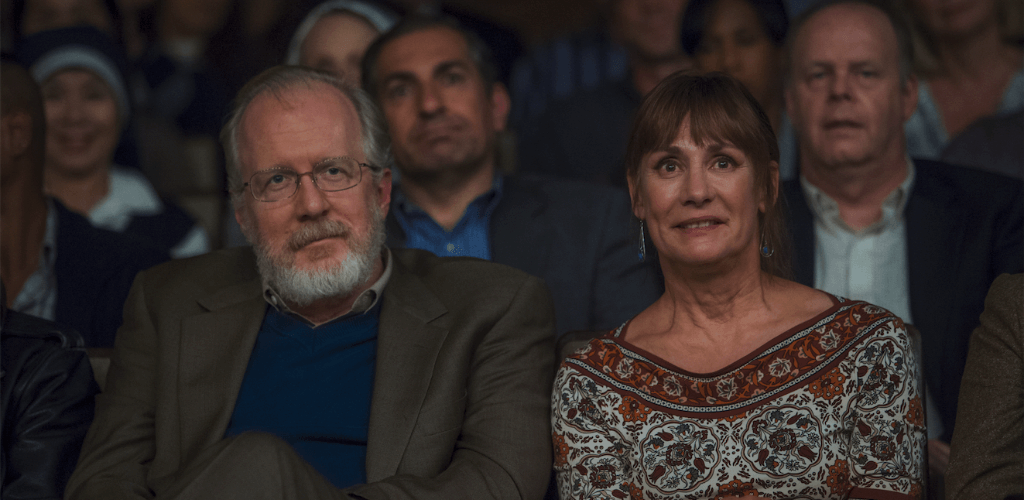

Allison Janney’s performance in I, Tonya is the first of the group that feels worthy of the gold. Janney plays Tonya Harding’s mother LaVona. It’s a role that could have easily devolved into stereotype. But there’s a baked-in authenticity to LaVona’s working-class grit. This is a woman who wants to teach her daughter everything she had to learn the hard way. Nothing is earned. If you want something, reach out and take it because if you stand still long enough someone else will take it instead. It’s a mantra LaVona drills into Tonya from birth to painfully mixed results. But for LaVona, any negative results are Tonya’s fault. There’s a moment where she watches her daughter skate on TV in the middle of the diner where she works as a waitress. Her boss yells at her to return to her customers, but she stares at the screen oblivious — a curious mixture of pride and contempt in her eyes. If Tonya can’t win a medal, it’s not her fault. She raised a winner. LaVona watches to the end, shakes her head, and gets back to work.

LaVona shares a lot in common with Laurie Metcalf’s Marion in Lady Bird. They both have the same crusty exoskeleton, but there’s something markedly different going on beneath the surface. LaVona’s heart is ice cold; Marion’s is a dripping mixture of shame and regret. Few would know that though, certainly not her daughter. In Lady Bird’s eyes, her mom is just another adult who doesn’t get it — a mean and demanding woman with expectations no child could ever live up to. But we see the truth. There’s a microcosm of her character in a masterful scene where Marion is dropping Lady Bird off at the airport. Marion is mad at her daughter again and let’s her know it. She drives off without saying goodbye. But as she drives around the block, the camera stays tight on her face and we see the real Marion emerge in real-time. Her shame rises to the surface. She so desperately wants to be the mother she never had, but she keeps making the same mistakes. Tears roll down her face and suddenly she knows what she has to do. She’s going to turn around. She’s going to apologize. She’s going to be everything she’s always wanted to be. Only…it’s too late. The plane is in the air. And in her heart of hearts, Marion knows that even if she had gotten her second chance, the results would have been the same as before. Metcalf is without question the best supporting actress of the year.

Best Supporting Actor

Willem Dafoe — The Florida Project

Woody Harrelson — Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Richard Jenkins — The Shape of Water

Christopher Plummer — All the Money in the World

Sam Rockwell — Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Of all the major categories, Best Supporting Actor is the weakest this year. Woody Harrelson shouldn’t be nominated. Chief Willoughby is certainly a sympathetic character in Three Billboards — a police chief dying of cancer blamed for an unsolved murder — but there’s too much Harrelson here and not enough Willoughby. Most of the character consists of the profane outbursts Harrelson is known for. But even the few moments of sincerity don’t work. His voiceovers are long and sappy. His relationship to his wife and kids feels off. And the twist at the end of his arc is poorly executed, leaving us with the same sour taste that brings down the rest of the film.

Richard Jenkins is better in The Shape of Water. There are a few memorable moments. His character Giles dancing on the sofa with Elisa in their apartment, the tangible pain of the encounter with his crush at the restaurant, the bitterness of putting so much work into his paintings only to be brushed off yet again. But these are few and far between. Giles is too slight of a character to really make an impact. Great supporting performances cross paths with the main events in a memorable way. Jenkins’ scenes feel more like detours from Elisa’s story. He shows up in the bigger moments, but not in a way that adds to their power.

Willem Dafoe has the exact opposite problem in The Florida Project. He’s in the majority of the movie, so much so that his performance hardly fits the “supporting” bill. The problem is that Dafoe isn’t given any stand out moments. Bobby is the same person at the beginning of the movie as he is at the end. He shows up in the scenes with the highest emotions, but doesn’t show much himself. This could be intentional. Part of the charm of his character is that he feels like an actual person you could meet running a cheap hotel in Florida. There’s a rugged consistency to him that casts a spell. But I wish he had been given a few chances to take his character to the next level.

The fact that Christopher Plummer is as good as he is in All the Money in the World is a testament to both his talent and director Ridley Scott’s resourcefulness. Kevin Spacey originally played the part in full. Scott was literally putting the final touches on the film in post-production when he learned that Spacey’s career was over due to allegations of sexual abuse. Most directors would have shelved the movie and moved on with their life. Instead, Scott called up Plummer and re-shot all of Spacey’s scenes. Thankfully, nothing about Plummer’s portrayal of J. Paul Getty feels tacked on. His performance is the heart and soul of the movie. Getty is the perfect filter to display the trappings of wealth. He’s the richest man in the world, but can’t enjoy a penny of it because he’s obsessed with maintaining his fortune. There’s a moment where Michelle Williams’ character willingly takes the losing end of a deal with Getty. His mind can’t comprehend what’s happening. She’s after higher values like love and sacrifice, but all Getty can assume is that she’s got a trick up her sleeve. We’ll never see Spacey’s version of Getty, but I have a hard time believing it could match the subtlety and gravitas Plummer brings to the table.

I’m pained to admit that anything about Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri deserves an Oscar, but as I think over the performances on this list, Sam Rockwell cuts the deepest. I wish Martin McDanagh had written Dixon with more subtlety, but this isn’t a writing category. Rockwell can only work with what he’s given, and from a pure acting perspective he’s the standout of the five. What separates Rockwell from his fellow nominees is an authentic emotional arc. When we first meet Dixon, he’s a lost cause — a loose cannon, loud-mouth racist on a collision course with destruction. But the events of the film lead him to a breaking point where he has to decide what kind of man he wants to be. Dixon’s prison of ego is shattered by an unexpected act of grace, and when the opportunity to do something honorable for the first time in his life comes along he grabs it by the horns. McDanagh is wise enough not to try and cure Dixon of his lifelong prejudice in two hours, but we do see the first halting steps toward repentance. After a lifetime of memorable character work, this is Rockwell’s first Oscar nomination. Hopefully it will be his first win too.

Best Actor

Timothée Chalamet — Call Me by Your Name

Daniel Day-Lewis — Phantom Thread

Daniel Kaluuya — Get Out

Gary Oldman — Darkest Hour

Denzel Washington — Roman J. Israel, Esq.

Daniel Kaluuya is clearly a decent actor, but Get Out isn’t the best showcase for his talent. His role is essentially the straight man in a film full of crazies. It doesn’t take Oscar talent to make puzzled reaction shots and awkward small talk. But where Kaluuya finally shines is when he’s hypnotized into the sunken place. The look of sheer horror on his face is so captivating it becomes the defining image of the movie. This is no doubt what earned Kaluuya the nomination, but he’ll need more than that to win the gold.

Denzel Washington is one of a handful of actors that can make a bad film worth watching. Roman J. Israel, Esq. has some serious problems, but Washington keeps us interested. The role is a nice change of pace for him. Israel isn’t a cookie-cutter hero. He’s a man who’s been fighting the system for so long, he’s forgotten why he started. Why keep punching when you always lose the fight? Why deny yourself the good life if nothing ever changes? Israel isn’t a bad man, he’s just hopelessly human. This is the second year in a row Washington has been nominated. But like Fences, Israel can’t live up to his talent. And like 2017, he’s edged out by better performances.

One of them is Daniel Day-Lewis in his supposedly final role as an obsessive dressmaker in Phantom Thread. The intensity Day-Lewis brings to each and every role can never be overstated. He’s a method actor through and through, and his Reynolds Woodcock is another towering portrait of a man teetering on the brink of madness. Woodcock is used to getting what he wants. He’s rich, powerful, and talented. He likes women when they’re objects to be chased, but bores of them when they’re housebroken. But in a woman named Alma, he finally meets his match. Their relationship grows increasingly twisted as Woodcock grows increasingly unhinged. You couldn’t ask for a better way to go out if this is indeed Day-Lewis’ swan song. Like Woodcock, Day-Lewis is a master artist and his talent will be sorely missed.

If the definition of a great performance is an actor completely disappearing inside his role, then Gary Oldman has achieved just that for Darkest Hour. Within 5 minutes, we completely forget we’re watching Oldman and allow ourselves to be tricked into believing we’re watching Winston Churchill in the flesh. The question is how much of that is world-class make-up and how much is world-class acting? Truth be told, it’s a healthy mixture of both. The illusion wouldn’t be the same if Oldman had just gained 100 pounds and changed his accent, but a prosthetic costume alone is nothing without an actor underneath capable of delivering the goods. Oldman embodies Churchill in all his contradictory complexity. He’s a kind, mean, saintly, son of a gun — barking insults one minute and talking tenderly to his wife the next. Oldman’s performance is both physical and emotional, and it could very well be his best work to date.

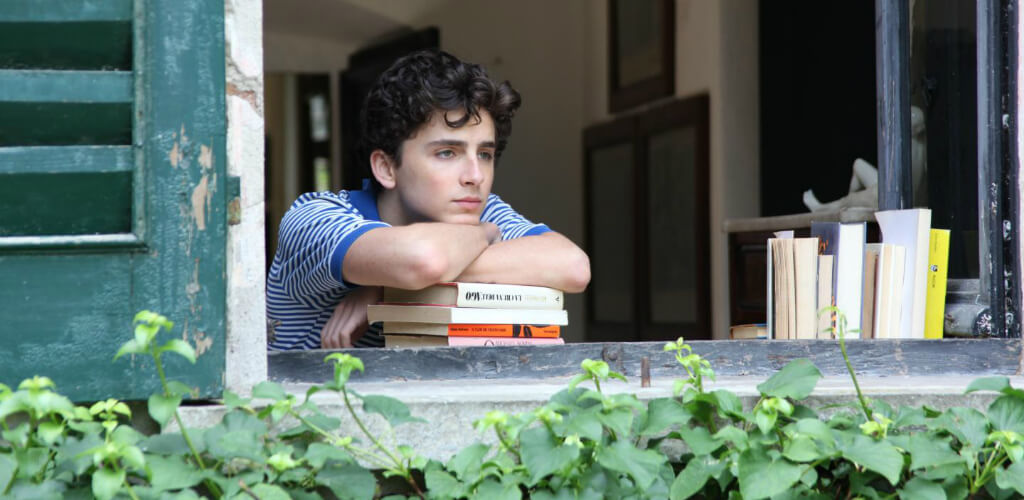

But there’s one actor in this category who matches Oldman’s feverish intensity without any makeup to hide behind. Timothée Chalamet couldn’t ask for a better calling card than his stunning turn as Elio in Call Me by Your Name. Chalamet showed up in three movies during 2017. His bit parts in Lady Bird and Hostiles were instantly forgettable, but no one will forget this one. The movie belongs to him completely. Not only is he in every scene, but the emotional mis en scène of the film is tied to his character. This is a movie about desire, the insatiable kind we experience most in the passion of youth. Much has been talked about the scene where Elio sexually experiments with a peach. The scene is the perfect distillation of his character. Elio has no idea why the peach turns him on, and when he’s done he’s filled with confusion and shame. His body and mind are flying in circles and he’s desperately looking for a place to land. Chalamet’s talent is as precocious as the character he plays. The sky’s the limit for this 23 year old. He better get used to the Oscars, and he better come prepared to give a speech.

Best Actress

Sally Hawkins — The Shape of Water

Frances McDormand — Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Margot Robbie — I, Tonya

Saoirse Ronan — Ladybird

Meryl Streep — The Post

Meryl Streep is a legend. Incredibly, this is the 21st time she’s been nominated for an Academy Award. Her turn as Kay Graham in The Post is a nice subversion of the roles we’re accustomed to seeing her play. We expect Graham to be a fearless feminist icon, upending the gender roles of the 70’s and turning heads in the process. Instead, Graham is meek and timid, a woman learning to find her voice in an industry dominated by machismo. Streep plays her part well, but there’s a staginess to her approach. The part feels like a Streep performance rather than a three-dimensional character. It’s an interesting addition to her filmography, but not enough to earn her another Oscar win.

The woman seemingly predestined to win is Frances McDormand for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. The buzz around her role has been strong and steady ever since the film first debuted on the festival circuit, capped off by a Golden Globe last month. But much like the movie itself, I was disappointed when I finally saw the real thing. McDormand isn’t bad by any means, but she doesn’t have that extra sizzle that screams Oscar. In fact, I found the performance curiously one-note. This is supposed to be a woman struggling with grief, but writer/director Martin McDanagh seems more excited about her throwing Molotov cocktails into buildings and shouting profane things for shock value. Maybe that’s just Mildred’s way of coping with her loss. Fair enough, but we need to feel that in her actions. The fact that we don’t is either a deficiency in acting or writing. I blame the writing.

Margot Robbie has come a long way in a short amount of time. Two years ago she donned pig tails and fishnet stockings to play sexy psychopath Harley Quinn. This year, she’s an Oscar nominee. It helps to have a character as rich and complicated as Tony Harding. Robbie could have played her a number of different ways. For I, Tonya, she chooses to portray Harding as an innocent bystander. Why is she such a ruthless competitor? Because she was taught as a child that winning was everything by an overbearing, abusive mother. What part does she play in the Nancy Kerrigan fiasco? None. All she wants to do was skate. We’ll never know if this is the real Harding, but it doesn’t matter. This is Robbie’s Harding, and that’s enough. It’s a no holds barred portrayal that’s as fun to watch as I’m sure it was to play. Welcome to the shortlist, Robbie. You’ve earned it.

Sally Hawkins’ smile is infectious. It lights up the screen and lights up our hearts. Director Guillermo del Toro uses that smile to full effect in The Shape of Water. This is a character Hawkins is born to play. Since Elisa is mute, everything we need to know comes from her face. And Hawkins just happens to have the most expressive face in the business. Her eyes dance with emotion — fear, wonder, joy — it’s all there, often at the same time. Her romance with the amphibian-man is peculiar, but understandable. Elisa knows what it’s like to be stared at and abused, picked and prodded. They’re both prisoners in their own ways, but in each other’s arms they’re free. It’s a magical performance that forms the perfect center for del Toro’s adult fairy tale world.

Saoirse Ronan isn’t a better actress than Hawkins, she just happens to perform in a better movie. While The Shape of Water goes off the rails in the third act, Lady Bird soars. Ronan received the role of the year and she makes full use of the opportunity. Not that Ronan hasn’t already proven her talent. The Irish actress is a three-time Oscar nominee, appearing most recently for 2016’s Brooklyn. Comparing Brooklyn and Lady Bird side by side shows the breadth of her range. In Brooklyn, Ronan plays a thoughtful, measured woman. In Lady Bird, she’s an outspoken, delusional brat. But Ronan manages to make both characters sympathetic and relatable. We were all Lady Birds once and still are if we’re honest. We’re frustrated when people don’t do what we want. We’re frustrated by a world that refuses to revolve around us. Only by coming to the end of ourselves can we ever hope to grow. Ronan’s Lady Bird covers the full length of this journey. It’s an honest, funny, beautiful portrayal that should earn Ronan her first trip to the podium.

Best Director

Christopher Nolan — Dunkirk

Jordan Peele — Get Out

Greta Gerwig — Lady Bird

Paul Thomas Anderson — Phantom Thread

Guillermo del Toro — The Shape of Water

From a directing standpoint, it’s hard to argue against Get Out’s effectiveness. Jordan Peele built a movie tailor-made for a movie theater. He knows all the right buttons to push, and he knows when to push them. The showing I attended was a blast. The audience yelled at the screen, screamed at the jump scares, and laughed at the dark stabs of comedy. I like to imagine Peele attending showings like this in secret, a hat on to cover his face but not his smile. I imagine the feeling he gets as each reaction he engineered explodes around him. Mission accomplished.

Paul Thomas Anderson has been on a shaky streak ever since his last masterpiece There Will Be Blood. The Master starts out strong but goes nowhere. Inherent Vice is a fun acid trip devoid of substance. But with Phantom Thread, Anderson is officially back. He’s regained the attention to detail that made There Will Be Blood so exquisite. Every scene is perfectly paced and perfectly shot. His fourth soundtrack collaboration with Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood could be his best. And most importantly, Phantom Thread is just gorgeous to watch from beginning to end. The film as a whole may not be perfect, but it’s a bona fide technical masterpiece that will be studied in film schools for years to come.

The same is true for Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water. As in Phantom Thread, every scene is perfectly crafted with arresting visuals, colors, and sounds. But Water also has a magical realism that allows del Toro to take things to a higher level like the dream sequence where Sally Hawkins dances around a ballroom in beautiful black and white. These are the moments that allow del Toro to fill the screen with every visual flourish he can muster. Like Phantom Thread, the script isn’t perfect and there are a fair share of narrative missteps. But del Toro’s technical acumen combined with the surreal glow of his adult fairy tale world is nothing short of magic.

And yet, as accomplished as Peele, Anderson, and del Toro are, they still can’t hold a candle to what Christopher Nolan achieves with Dunkirk. This is directing of the highest order. I can’t imagine the planning and painstaking detail needed to seamlessly integrate the three stories of the film into one coherent journey. The beach scenes employ hundreds of extras with IMAX cameras swooping in at all angles around them. The scenes in the air are the most thrilling plane sequences filmed to date — the viewer right in the middle of the firefight without ever losing touch of the big picture. And the moments on sea provide an intimacy that contrasts beautifully with the bigger moments of spectacle. Nolan is like a conductor — the resident maestro of organized chaos. He designed Dunkirk as an experience, and the 70 mm IMAX showings were the best money could buy.

Ever year, the debate in this category comes down to whether the Best Picture and Best Director trophies should go hand in hand. After all, how can the best movie of the year not be the best directed movie of the year as well? I sympathize with both sides of the argument. Last year I split the categories, giving La La Land Best Director and Moonlight Best Picture. But those were both perfect films. This year, there’s only one perfect film and that’s Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird. There’s more than just technical achievement to consider when thinking of great directing. The director is the grandmaster of the film set. Every single decision for every minute of the movie rests on their shoulders. As technically stunning as Dunkirk is, it’s held a notch back from perfection by being emotionally underwhelming. That means somewhere along the way Nolan made a wrong decision, whereas Gerwig got everything right. She wrote a sublime script and executed it flawlessly. Every scene jumps into the next at just the right moment. Every beat of the story unfolds with expert pacing. Every shot is perfectly positioned for maximum impact. Lady Bird is a masterpiece and Gerwig was responsible for every frame. She’s earned the honor of joining Kathryn Bigelow as the only women in Oscar history to win Best Director.

Best Picture

Call Me by Your Name

Darkest Hour

Dunkirk

Get Out

Lady Bird

Phantom Thread

The Post

The Shape of Water

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

The trailer for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is perfect. The film? Not so much. We need more movies that openly address sensitive topics like trauma, racism, and prejudice, especially in light of recent events in our country. But we need them to be handled with restraint and nuance, and that just isn’t Martin McDanagh’s cup of tea. McDanagh has a terrific cast at his disposal and manages to fill a number of scenes with raw power, but his penchant for handling painful topics with the subtlety of a sledgehammer makes for an uncomfortable two hours.

Darkest Hour is a film featuring a masterful performance by Gary Oldman as the great Winston Churchill, but it really isn’t much more than that. There’s nothing especially memorable about the side characters, visuals, setting, or plot. We remember Gary Oldman in expert makeup giving sensational speeches. That may be enough to earn Oldman an Oscar, but the movie itself doesn’t deserve one.

I’m happy Get Out is an Oscar-contender simply because it means so much to the black community, but I’m still not convinced it’s a great movie. Jordan Peele certainly gets points for originality. He crafted a movie with all the classic horror/comedy tropes and still found a way to tackle racism head-on. And yet, the horror/comedy tropes can’t be ignored. This is a film with over-the-top blood and guts (a doctor performs a homemade brain transplant in all its gory glory) and slap-stick humor (the buddy of the protagonist gets increasingly worried back home and cracks off zingy one-liners). I’m not opposed to a horror movie winning Best Picture, but it would have to be of a higher caliber than this one. I’d give The Shining the trophy in a heartbeat. But Get Out feels more like Cabin Fever — a B-movie that knows it’s a B-movie and gives audiences a ride to remember.

There couldn’t be a movie more timely than The Post. When a pathological liar lives in the white house, newspapers are no longer just a nice thing to read on Sundays; they’re the very backbone of our democracy. How can the public act if they don’t know the truth? Many have accused the The Post of being paint-by-numbers Oscar bait. I see their point, but even a painting from numbers can still be beautiful to look at. The movie certainly isn’t perfect. Steven Spielberg falls victim to mawkishness, especially near the end. But the cast delivers, and there’s nothing more exciting than watching an underdog take on a giant. A free press is something we too often take for granted. As history repeats itself, we desperately need the reminder.

Phantom Thread leaves a bitter after-taste, but it’s oh so sweet going down. Paul Thomas Anderson has created the most beautiful film of his career. The visuals are sumptuous. The soundtrack is heavenly. The costumes and set pieces are out of this world. But underneath the glitz and glamour lies a perverse underbelly that strikes when you least expect it. This is all part of Anderson’s bait and switch. He’s crafted the film just like the dresses Daniel Day Lewis’ character makes — gorgeous on the outside but empty underneath. We marvel at the craftsmanship, but leave the theater with the stench of death. The film is too odd to be a Best Picture threat, but it’s so exciting to see Anderson back on his game.

In a world gone mad, we need more adult fairy tales like The Shape of Water. For the first half of the film, Guillermo del Toro sweeps us away. We dance along to Elisa’s routine and soar when she finds love in the most unexpected places. If only del Toro had maintained the magic. The movie should have stayed a breezy, 50’s throwback with a quirky bent. Instead, it becomes a dark, twisted tale of violence and prejudice. Del Toro should have picked one or the other. The jarring tonal shift throws the film off course. The technical brilliance, masterful acting, and beautiful visuals remain for both hours, but our hearts are only invested in the first.

What sticks with me most about Dunkirk is the ticking clock. We hear it right from the start. Time has played a role in every film Christopher Nolan has made, but his use of it here feels the most potent. We follow three perspectives by land, air, and sea separated by an hour, a day, and a week. Nolan criss-crosses the narratives, all while sneakily bringing the timeline together into one final climax. What a masterful way to tell a story. By the end of the movie, we feel like we’ve seen every angle of the Dunkirk conflict firsthand. And we’ve taken it all in with the most immersive theater experience cinema can offer. Dunkirk only has one flaw — it lacks a true emotional payoff. We get a momentary burst of feeling when the ships enter the harbor, but then we’re right back in the battle again. Nolan’s last film Interstellar was too emotional. Dunkirk is too cerebral. When he finds a way to connect the head with the heart, it will be time to claim the Best Picture trophy.

Call Me by Your Name lacks the technical craftsmanship of Dunkirk, The Shape of Water, and Phantom Thread, but it’s no less stunning to watch. The power of the visuals are found in emotions, not mechanics — specifically the emotions of a 17-year-old boy who feels so much inside he might just burst. Everything we see is through the eyes of Elio and director Luca Guadagnino continually finds new ways to communicate his inner world. Fruit and food are on every table. Perfectly toned bodies lie in sunglasses next to flowing streams. Sunlight shines through the Italian countryside on fertile wildlife brimming with possibility. This is a movie about desire, and the things our hearts want but can’t have. But rather than condemn that desire as we so often do in the Church, Guadagnino sees it as a necessary rite of passage. As Elio’s dad says, “We rip out so much of ourselves to be cured of things faster than we should that we go bankrupt by the age of thirty…but to feel nothing so as not to feel anything — what a waste.” This is a movie some Christians will avoid because of the gay relationship at the center, but that’s just another symptom of the problem. Spending two hours observing someone different than you won’t corrupt your soul. In fact, it might help you realize how much we have in common.

There’s one movie every year that feels different than all the rest. Last year, it was Moonlight. I knew the minute I walked out of the theater that no other film that year could top it. This year, I had the same feeling about Lady Bird. I always knew Greta Gerwig was a gifted actress, but I had no idea how deep her talent ran. The script alone would have been a game changer, but Gerwig had even more to offer. Her control as a director is masterful. The opening scene ends in a darkly comedic moment where Lady Bird rolls out of a moving vehicle because she doesn’t like something her mother said. Gerwig does a fast cut from this to the opening credits where we see Lady Bird sitting in church service with a cast on her arm looking glum. I knew from that moment on that this would be a special film. The question was could Gerwig maintain the same quality of writing, acting, and directing for the entire movie? She can, and she does. But what truly puts Lady Bird over the top is its redemptive final act. Gerwig has more on her mind than just witty banter and clever editing. She wants to bring us on a journey. We are all Lady Birds — pretending to be what we’re not and bucking every rule and authority that comes our way. Too often we attempt to cure this with law and religion. But the only thing that can penetrate the endless depths of our ego is grace. At the end of the film, when Lady Bird reaches her lowest point, she stumbles into the one thing she’s always rejected: a Church. Maybe she’s seeking God. Maybe she’s just nostalgic. But her next phone call after leaving the service is to her mom — the same mom she’s treated like garbage the entire movie. She stumbles through a voicemail message and ends on the two words we all learn to say when we finally grow up: “Thank you.” It’s the perfect ending to a perfect film. Lady Bird is the best movie of the year.

Join Us…

We’ll be live-tweeting throughout Oscar night! Follow us on Twitter to get in on the action: twitter.com/cinemafaith.