Lighthouses hold a romantic fascination for most of us. Standing on the edge of civilization, broadcasting a beacon of light to those struggling to get back home, showing the way in the fiercest of storms and warning off ships from dangerous reefs. How many of us have heard our ministers use lighthouses as an analogy in one story or another from the pulpit? The state I live in, Michigan, has approximately 124 lighthouses (at one time the number was 247). Some people make one of their life goals to “touch” each one (a very difficult task involving two-tracks, row boats, swamps, poison ivy and — probably — some trespassing).

But the fictional lighthouse of this film, faithfully based on the very popular 2012 M. L. Stedman novel of the same name, is not at all like Michigan lighthouses. It stands on a jutting of rock, the top of a submerged mountain protruding from the depths of the ocean 100 miles west of the western coast of Australia. Janus Rock marks the turbulent meeting of the warmer Indian Ocean to the north and the frigid Great Southern Ocean to the south.

The Story

Set in the 1920s the lighthouse keepers of that time were visited by a supply boat and letter bag every 3 months and got one week shore leave every year. Consisting (in the novel) of a square mile of land with the lighthouse, the light keeper’s small residence and a few storage and out-buildings life on Janus Rock was a spartan, solitary existence. Chief responsibility among all else was to light the mercury lantern every evening, to keep it operating through the most furious of storm (even if that meant staying up with the light all night), and to extinguish the light at dawn (to preserve the precious fuel). From the novel: “Each night the air sang with the steady hum of the lantern as it turned, turned, turned; even handed, not blaming the rocks, not fearing the waves: there for salvation if wanted.” And there were many other regulations regarding fastidious bookkeeping of the weather, expenses and ships seen, the raising of flags on a regular basis (even if the light keeper were the only human within 80 miles), and meticulously keeping the light’s brass and lenses sparkling clean.

To this job comes WW I, war-scarred Tom Sherbourne (in an Oscar-worthy performance by Michael Fassbender who has already been Academy Award nominated for Steve Jobs and 12 Years a Slave). With no close family — just a father from whom he is painfully estranged — he wonders why he was spared when so many others lost life, limb, or mental competence. Tom suffers from what we would now call PTSD.

To this job comes WW I, war-scarred Tom Sherbourne (in an Oscar-worthy performance by Michael Fassbender who has already been Academy Award nominated for Steve Jobs and 12 Years a Slave). With no close family — just a father from whom he is painfully estranged — he wonders why he was spared when so many others lost life, limb, or mental competence. Tom suffers from what we would now call PTSD.

From the novel: “To make sense of it—that’s the challenge. To bear witness to the death, without being broken by the weight of it. There’s no reason he should still be alive, un-maimed. Tom… weeps for the men snatched away to his left and his right, when death had no appetite for him. He weeps for the men he killed.”

Tom seeks to flee humanity and takes the lighthouse keeper’s position which has become available due to the present keeper going insane. The rigid regimentation and isolation of this life suits him, and he thinks he could live in that solitude, doing “his duty,” for the rest of his “undeserved” life.

Enter Isabel

As must happen in romantic melodramas, when Tom is interviewed in the sea-side village of Partageuse for the light keeper position he is asked to have dinner with town notables and he meets the beautiful young schoolteacher Isabel Graysmark (played by Alicia Verkander — so memorable in Ex Machina and an Oscar winner for last year’s The Danish Girl). She has lost her two brothers in the war and she feels his grief. Their chemistry is immediate. Tom departs for Janus Rock on the tiny but dependable commuting and stores tub Windward Spirit, captained by Ralph Addicot (a wonderful turn by the yeoman actor Jack Thompson who has a long resume but few starring roles).

Once on the rock, Tom finds the numbing routine of his job soothing but cannot forget the beautiful, dimpled Isabel. Their courtship continues with letters exchanged every 3 months and quickly (in the film) moves on to their marriage. Isabel happily makes her new home on the desolate island where she understands that her husband’s first responsibility is not her, but tending to the Janus Rock’s light beam searching out to those at sea. But still, Tom and Isabel both find happiness they have never known and they plan to bring up their children in their isolated bliss.

Temptation

And then come the heartbreaking miscarriages. After the second one (at an advanced stage of her pregnancy) Isabel becomes obviously and severely depressed and Tom is desperate as to what he can do. She refuses to go back to her parents for respite due to her shame of not being able to bear children. One day praying at the crude crosses for her children who never lived (“…and lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil…”), she hears an infant’s cry almost at the same time that Tom sees a small dinghy drifting ashore. As Tom runs to the boat, with Isabel following closely, they find within the gunwales the cold, blue body of a dead man and, much to their wonderment, a breathing, crying infant of just a few weeks of age.

What could be more natural (for all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God — Romans 3:23) than to see this as their opportunity? It all seems so perfect… a child delivered to them with no identification and no living parent, if that is what the corpse represents. There is no idea as to who the man is or his motive. Why not take it as their own? The timing would work if they said their child came early, which it did. Isabel rationalizes this event as God’s answer to her prayers. Tom knows it is wrong but worries what will happen to Isabel if this infant, to which she is already bonding, is taken from her with the next run of the Windward Spirit.

Isabel pleads with Tom, “Our prayers have been answered. The baby’s prayers have been answered. Who’d be ungrateful enough to send her away?” It is important to note that the deceit born at that moment does not happen by throwing a switch… by making big plans and a final momentous decision. It is just allowed to happen. Tom succumbs to Isabel’s wishful thinking that this can and should happen without consequences; that it is God’s will and blessing. It is in the same way that temptation confronted Adam and Eve. But deep down Tom knows the truth of their sin of covetousness and prays “Forgive me Lord, for this and all my sins. And forgive Isabel. You know how much goodness there is in her. And you know how much she’s suffered. Forgive us both. Have mercy.”

Isabel pleads with Tom, “Our prayers have been answered. The baby’s prayers have been answered. Who’d be ungrateful enough to send her away?” It is important to note that the deceit born at that moment does not happen by throwing a switch… by making big plans and a final momentous decision. It is just allowed to happen. Tom succumbs to Isabel’s wishful thinking that this can and should happen without consequences; that it is God’s will and blessing. It is in the same way that temptation confronted Adam and Eve. But deep down Tom knows the truth of their sin of covetousness and prays “Forgive me Lord, for this and all my sins. And forgive Isabel. You know how much goodness there is in her. And you know how much she’s suffered. Forgive us both. Have mercy.”

The months go by and the love that encompasses the new “family” is warm and glowing… such a good thing it would seem. When they return to Partageuse with “their” newborn (who came “just a little early”) the joy of the new grandparents is heartwarming… how could this not be right? And then, at Lucy’s christening, the other foot drops. Tom sees Hannah Roennfeldt (Rachel Weisz — an Oscar winner for 2005’s The Constant Gardner but infrequently seen lately) kneeling in prayer at a memorial to her husband, Frank, and her infant daughter — lost at sea just two years previously. Tom is racked by guilt as he is certain their daughter Lucy is actually Hannah’s daughter Grace. And we see that Tom and Isabel’s decision which seemed to harm no one had, in fact, devastating consequences. We viewers know that many of our sins (perhaps sins of indifference or omission) have hurt and continue to hurt people but we shield ourselves from the ramifications of our action, or inaction.

A Movie That Wears Its Faith on Its Sleeve

The movie follows the novel faithfully, of course leaving out some of the subplots that make Stedman’s storyline so rich and satisfying. Nonetheless, this is a wonderful film full of spirituality (less than the book but still there.) Characters pray and ask God for direction in their life. They have faith that there is a God; that there is right and wrong; and that how we conduct our lives matter. They also believe that forgiveness, no matter how difficult, is central to living a life of peace and equanimity. Hannah cherishes the memory of her husband Frank, who was of German heritage and accent; who was constantly persecuted for it by a population that lost so many people to the war fought in that far-away country. She especially remembers Frank saying, when she asked him how he could repeatedly turn the other cheek, “To resent you have to do it all day, every day. To forgive you must only do it once.” (This is much more beautifully said in the novel.)

As the movie draws to a close, there is a beautiful scene (MILD SPOILER) where Isabel says to Tom “I’m so scared, love. So scared. What if God doesn’t forgive me?” and Tom replies “God forgave you years ago. It’s about time you did too.” Would that we could all grasp and believe that, and stop punishing ourselves for our sins long washed “white as snow” by our Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. We know that and most of us hear that every week, but we keep trying to earn our salvation. Yet it is there, just as the lighthouse beacon is “there for salvation if wanted.”

Screenplay author/adapter and director Derek Cianfrance (Blue Valentine, The Place Beyond the Pines) did, I think, a beautiful job here. There was a lot of story to tell and he did so hitting most of the right notes. The contrast between the wide, awesome vistas and the intimate close-up conversations constantly kept my interest without being too intense. The word Janus comes from the Roman god of doorways, or beginnings and endings, represented as one head with two bearded faces back to back, looking in opposite directions. Cianfrance helps us see “Both Sides Now” (for those of you old enough to remember Joni Mitchell). This is a kind movie that embraces all of its characters. We see “both sides” of the actions of all the leads. We wonder what we would do in their situation.

The Finished Product

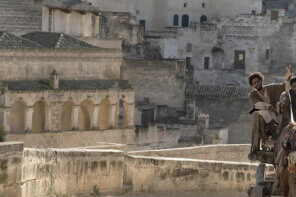

The Light Between Oceans is flat-out beautiful — many glorious scenes of sunsets and crashing waves, of quaint villages (the village filmed was in Tasmania) and characters whose lives are lived hard (locals were used for many of the extra parts). I loved the novel and I loved the film just as much. In an age where so much of what we watch is fantasy that removes us far away from our day to day struggles (and a little bit of that is ok, but look at the movies of this summer…) this is a film that helps us deal with our inability (without God’s strength) to resist evil and sin, and our justifications/rationalizations as to why we repeatedly make those choices. There are no “bad” people here, only humans who struggle when placed in difficult situations. Everything that is done has a “good” rationale behind it, but people do things that are wrong and they know it. And the consequences follow.

Two points that take away from my admiration for the film. First is my disappointment in the often whispered dialogue. I am hearing impaired (but usually do ok with hearing aids.) However my wife is not and we were both very frustrated by the loss of lines of hushed dialogue due to the sounds of the surf or other background noise. (Perhaps it was just the theater we were in?) And secondly the location they chose for Janus Rock was odd. In the novel Janus Rock is described as a sliver of rock with two Norfolk pines and scrub brush, rising from a beach on one end to a stark cliff on the other with the lighthouse perched on the cliff’s edge. The lighthouse rises far above anything else on Janus Rock giving its beam a 360 degree scan. The producers, however, chose to use New Zealand’s South Island which is not at all like the novel’s description — much larger with rolling hills. And most egregiously the lighthouse is set low on one end of the island and its beacon would be blocked by the higher hills behind it for much of its rotation. That does not seem to fit the stated purpose of Janus Rock reaching out in all directions to warn ships of its location and help them verify where they were positioned.

Two points that take away from my admiration for the film. First is my disappointment in the often whispered dialogue. I am hearing impaired (but usually do ok with hearing aids.) However my wife is not and we were both very frustrated by the loss of lines of hushed dialogue due to the sounds of the surf or other background noise. (Perhaps it was just the theater we were in?) And secondly the location they chose for Janus Rock was odd. In the novel Janus Rock is described as a sliver of rock with two Norfolk pines and scrub brush, rising from a beach on one end to a stark cliff on the other with the lighthouse perched on the cliff’s edge. The lighthouse rises far above anything else on Janus Rock giving its beam a 360 degree scan. The producers, however, chose to use New Zealand’s South Island which is not at all like the novel’s description — much larger with rolling hills. And most egregiously the lighthouse is set low on one end of the island and its beacon would be blocked by the higher hills behind it for much of its rotation. That does not seem to fit the stated purpose of Janus Rock reaching out in all directions to warn ships of its location and help them verify where they were positioned.

But overall it was a wonderful evening at the movies for my wife and me. The acting was great, the characters were almost all likeable and relatable. The story was immensely moving. So why has it faded at the box office? Well, it opened on an unfavorable weekend (Labor Day) to mediocre reviews, much like Me Before You. Shannon Plumb, spouse of Derek Cianfrance and herself a filmmaker, wrote a piece for “The Talkhouse” were she asks if the public is losing their ability to be romantic and critics, “like Lemmings, are jumping off the cliff with all the other unsentimental rodents.” It brings to mind the saying that it takes 2 years to make a movie, 2 hours to watch one, and 5 mins (at the keyboard) to destroy one. I don’t quite believe that critics have that power but when a generation of critics sours on one particular genre of film (romantic melodrama), there is a point to be made.

Despite these quibbles, if you enjoy spiritual content in your film without being preached to, see it. If you enjoy examining the human condition, see it. If you enjoy great acting and great locales, and yes, if you enjoy romance tainted with some tragedy — see this film. I believe you will go away rewarded.