If you were to drive by one of my family’s gatherings you could look into the dirt driveway and see, affixed to several bumpers, a sticker that reads: “England Get Out of Ireland.” Although we have quite a bit of Irish Catholic blood in our veins, there is also a significant amount of English in it — hence my surname. Despite that the Irish tends to dominate many of our gatherings, for many of us (myself included) this is the heritage that steels itself most strongly in our hearts. We sing it, we read it, we watch it, and we live it with a pride.

The first time I saw In the Name of the Father I was nine or ten. I remember the movie being incredible, even then. It’s funny, now that I have my own children, how conscious I am of what they hear — reflecting back on what I remember of the movie I think we sometimes focus on the wrong thing. What I mean is, when I re-watched this for the first time as an adult I was shocked at the amount of vulgar words… not because they were there, but because I didn’t remember them being there when I watched it as a kid (a time where you might think hearing those words would give that wide-eyed Ralphy look from A Christmas Story when he stands too near the basement vent).

What I remember was the unfairness of the situation. I remember the sadness, and the being moved to never back down when justice is due. It’s an interesting point, one of context rather than the main line: what do we allow our children to hear? What impact will it have on them? How much do we trust them to filter what really matters?

Maybe it was the heated discussion of the adults in the room that followed. Not heated in disagreement, but in passion. Anyways, before I end up too far in the weeds, the point is this film, like many others, can become a stumbling block via its crassness; but the reality is the world is crass and we can replace that crassness with a saccharine cordiality (like we see with so many “Christian” films) or we can view the broken world through the light of promised redemption.

In the Name of the Father is a film that pulls no punches and moves us viscerally and spiritually to seek.

The Story

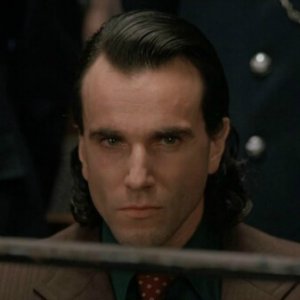

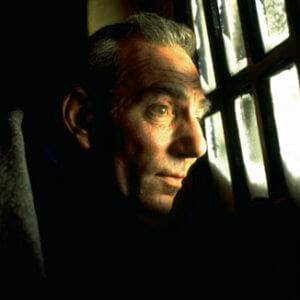

This is a film based on the very real events surrounding a family from Belfast, Ireland at the height of conflict between the IRA (Irish Republican Army) and the colonialist Brits occupying the country of Ireland. In it we follow Gerry Conlon’s (played by Daniel Day-Lewis) story of how he, and four others, were wrongfully convicted of the Guildford pub bombings in 1974. Not only are Gerry and the other members of the “Guildford Four” arrested, but members of Gerry’s family are absurdly connected to the crime, including his father Giuseppe (played by Pete Postlethwaite).

The story itself is told, first, as an accounting by Gerry himself to an attorney. We are taken into his world after a brief moment of watching his attorney (Emma Thompson) listening to one of the tapes Conlon has recorded to detail his account. From then on, until we are brought “up to date,” we are thrown into Gerry’s world with occasional voice-overs — these are used rarely and the story itself is told through the interaction of the actors.

The Actor’s Power

In film, on stage, in life, when we see a strong performance we don’t even realize how good it is. It’s the deficiencies in others that highlight the subtlety of something truly great. In film specifically it can be said that almost all “good” acting is the result of better directing and casting. This, however, is one of those few films in which the performance from the cast is more than any direction could provide.

When the voice-over is used (especially upon other viewings) it is incredibly moving because of subtle vocal inflections from Day-Lewis: you hear the moments of his voice breaking, but almost miss them — he wants you to hear the rawness of this as an actor, but as the character he wants to hide his weakness, and the balance is struck perfectly.

When the voice-over is used (especially upon other viewings) it is incredibly moving because of subtle vocal inflections from Day-Lewis: you hear the moments of his voice breaking, but almost miss them — he wants you to hear the rawness of this as an actor, but as the character he wants to hide his weakness, and the balance is struck perfectly.

The moment Gerry is getting on the boat in Belfast to head over to London, and he turns to look back at his father and says, “I wanted to call out to him. Say his name for the first time…” is one of those rare moments, a complete moment in film that you can come back to and have your heart broken by the simple sadness of this fractured moment. You hear him, and you hear him hiding it; and most importantly we SEE him do the same. We see his hesitancy, his weak recovery of his senses to yell out, “Da. I love you da,” almost half-heartedly, and the camera following Giuseppe deep in thoughts of concern and hope for his son.

This is just one example from a film packed with incredible acting. This shouldn’t be a surprise, right? I mean it is Daniel Day-Lewis, Emma Thompson, and Peter Postlethwaite carrying an already moving story.

Contemporary Context

This film, although historically dated, still holds relevance to the world around us today. The situation in Ireland holds several parallels to the world we now know. I don’t want to turn this into a sermon in which I provide you with the conclusions I’ve drawn, but I do hope to point to three specific (and heated) topics that this film may cause you to think more holistically on — as I did after re-watching it this year.

Iraq, Afghanistan, and Wars of Occupation

So, the thing that kicks the movie off is an act of terrorism committed by the IRA in London. The “war” between Ireland and Britain is one of unwanted occupation balanced by the fears of Protestants that their minority status will be exploited. The British military is literally roaming the streets of Belfast in fear of snipers (think of all the disguised combatants we read about in Iraq and Afghanistan). This is probably forgotten because externally the Irish and English are very similar. They are all white and European. Sometimes, in our POC (people of color) vs. White culture we forget that within those two very broad groups there exists significant cultural discrepancies.

Maybe it’s because the oppressed people group looks more like me that this parallel becomes stronger. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. That may be one small step towards empathy, towards avoiding that hard line of thinking without considering the other.

Guantanamo

Very closely related to this is the act that is passed following the pub bombing: an act to hold suspects of terrorism without a formal charge, and essentially without any rights. This film is all about the abuse that arises from that. As the movie plays out we see that not only is a false accusation a horrible injustice, but at one point Gerry is actually pushed towards a violent protest, a war if you will, against his accusers. In a way it is this very act that doesn’t dissuade terrorism, but is its greatest promoter.

Guantanamo is not different at all. We want it to be. I’m sure on some level (as probably happened in Britain) terrorist attacks were prevented that we never knew. But is the price of justice worth it? I don’t think, despite our passionate leanings, we (or our leaders) could ever give a legitimate answer. Ultimately, as Christians, we know that this will never bring true healing — that is the place of reconciliation, which requires vulnerability.

Guantanamo is not different at all. We want it to be. I’m sure on some level (as probably happened in Britain) terrorist attacks were prevented that we never knew. But is the price of justice worth it? I don’t think, despite our passionate leanings, we (or our leaders) could ever give a legitimate answer. Ultimately, as Christians, we know that this will never bring true healing — that is the place of reconciliation, which requires vulnerability.

In the film Giuseppe is the model for this. He is gracious, even to his persecutors; he holds no place for violence in his heart, only petitions for justice and kindness in the face of oppression — he truly repays evil with good. It isn’t until Gerry sees for himself the horror of the path of violence that he realizes how right his father is.

Black Lives Matter

For me (especially being Irish) hearing stories like this, seeing the signs “Irish Need Not Apply,” reading Swift’s A Modest Proposal, gives a more relatable position (I do not mean that I understand, that needs to be clarified) to the Black Lives Matter movement. Again, I think seeing it happen to people who look like you can really shift the perspective you use to approach what is going on today with a part of our culture we may not be connected to, or have any understanding for.

I don’t want to milk the comparison for more than it is. It is a frame of reference, a place for empathy to grow. The specifics of how that may play out in our day to day lives are still situational. For me the strongest point of the film is this fact that reconciliation between the sides needs to occur. The IRA has committed horrible acts that must be answered for, that can’t be explained away by “oppression.” Centrally, however, is the need for the powers that be to cease their abusive and oppressive practices, to right the wrongs they are capable of, and to provide an equal portion of justice for the mistreated as they demand of their minority counterparts.

Final Thoughts

In the Name of the Father will, hopefully, lose its historical and contemporary context someday. I think we’d all like to see racism, military occupation, terrorist attacks, torture, and wrongful imprisonments end. It is not foreseeable until there is a more perfect ruler than any of us can offer up; but yesterday, today, and forever we know the spirit it will take to overcome the world. It is the spirit of Giuseppe’s bold humility, his sense of justice, and his unwavering adherence to it in the face of great oppression. It is the spirit of the Christian Church’s origins, the one that took in the poor, sick, and oppressed, that amazed the Roman Empire marginalizing these very people.