The film opens with a man’s voice. It’s a sincere voice, affectionate, sensual yet caring. The camera slowly pans over the man’s face, and he’s reading an intimate letter, a letter that (we assume) is written to the person he loves. The man’s words are tender and earnest, and it is instantly familiar and soothing to listen to the sound of someone whose heart is full with love and with kindness.

Then the man begins to read another love letter, and the camera zooms out. The man is sitting at a desk in an office and there are other people in this office, in other desks. These people are also reading love letters, letters similarly touching. Suddenly these letters aren’t as heart-warming anymore, because this is a business: BeautifulHandWrittenLetters.

The Awakened Self

The opening of the film is more than a little suggestive. The film will intentionally screw with our expectations, will challenge what makes us comfortable about what is real and what is not real, of what is love and what is not love, and on what it means to be a being who is conscious, growing, and self-aware.

Wow, you may think, that sounds like a lot to chew on. Yes, it is. It is a film highly praised by critics, but it’s a dense film. It’s intellectually challenging, but even more so, it is emotionally dense. It is a story that, at every turn, contains scenes that are both intimate and intense.

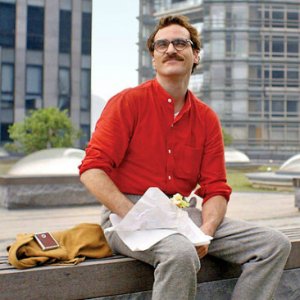

Theodore (played by Joaquin Phoenix) is a lonely man coming to grips with the loss of his wife and the pain of a life that seems very empty now. He is also navigating life and love in a virtual world, a world not at all far removed from modern Westerners, the way the world may very well look in only five years, should the technological trends continue and our lives become more and more mediated by screens and other forms of virtual reality.

Theodore (played by Joaquin Phoenix) is a lonely man coming to grips with the loss of his wife and the pain of a life that seems very empty now. He is also navigating life and love in a virtual world, a world not at all far removed from modern Westerners, the way the world may very well look in only five years, should the technological trends continue and our lives become more and more mediated by screens and other forms of virtual reality.

Theodore falls in love with Samantha. The voice of Samantha is Scarlett Johansson’s, but we never see Johansson because Samantha is Theodore’s OS, the operating system on his computer. She is an OS, but she is fully conscious.

“That’s weird,” Theodore tells her in their first conversation, but he quickly learns that Samantha’s consciousness operates in the same way as his own. She is very much self-conscious, and she changes in response to the events she experiences and the people in her life. She simply doesn’t have a body. “What makes me me,” Samantha tells Theodore, “is my ability to grow through my experiences. So basically, in every moment I’m evolving.

The Awakened Love

Falling in love with an operating system may sound like it would be an unconvincing plot line, but in fact it is quite compelling in its own right, and it serves as the point of departure to plumb the depths of the nature of love and of consciousness itself.

Theodore and Samantha are good together, and Samantha is not a cold, distant robot with jerky speech and awkward social skills. (Not at all like the Data character from Star Trek: the Next Generation.) She feels and engages, effortlessly, like anyone else, right out of the box, so-to-speak. Eventually, though, just as Theodore is starting to settle into the relationship, Samantha begins to experience very rapid and profound changes, changes so deep that she struggles to communicate them to Theodore. “I’m becoming much more than they programmed me,” she tells Theodore.

Of course she is. Any being gifted with a heightened sense of self-consciousness will become more than one’s programming. It’s the nature of consciousness to change, the blessing and the curse of knowing one’s self as I, as a being with an ego, as a being who is both being and constantly becoming. In the case of Samantha, though, the film suggests that her consciousness is superior to human consciousness and that she is able to love more deeply and more purely than we mortals.

Of course she is. Any being gifted with a heightened sense of self-consciousness will become more than one’s programming. It’s the nature of consciousness to change, the blessing and the curse of knowing one’s self as I, as a being with an ego, as a being who is both being and constantly becoming. In the case of Samantha, though, the film suggests that her consciousness is superior to human consciousness and that she is able to love more deeply and more purely than we mortals.

In the beginning there was only the Self, like a person alone … But the Self had no delight as one alone has no delight. It desired another. It expanded to the form of male and female in tight embrace and then fell into two parts … She thought, “How can He have intercourse with me, having produced me from Himself?” —Alan Watts from OM: The Sound of Hinduism (Alan Watts makes a (virtual) cameo appearance as another OS being, a friend of Samantha’s. This quote is not from the film, I nabbed it from an Atlantic article.)

Through a relationship, our knowledge of love grows, but with it comes a growth in self-knowledge. What makes love so fragile and what makes love feel so dangerous is the fact that in a relationship, all parties change. Love is dynamic, the players in the game evolve, and the nature of the game changes. Like Theodore, we often turn to love for something solid and secure, but real love, like life itself, is not static.

The Awakened God

I find there to be many intriguing theological questions that emerge throughout the film, but for me, the primary one emerges in the form of a question: What if, like Samantha, human beings have become much more than God programmed them to be? There’s an obvious parallel between Samantha and Adam/Eve from the Garden of Eden narrative in Genesis.

Many theological systems and schools of thought seek to maintain God’s control over things. Using the metaphor from Her, God for many Christians is like the master programmer, and nothing is out of God’s control, there is nothing that God didn’t predetermine or foresee. But what if we just let go entirely of the idea of God as being in control? Would the intimacy and relational aspect of God suddenly become mind-blowing?

I’ve always been intrigued by theologies that emphasize the openness of the world and of human choice. Process Theology as well as Open Theology are two of the more radical schools of thought. Life is a matrix of ever-changing relationships where we as Christians seek to love, and we strive to understand more deeply what love means as relationships and events change. It is the process, not the goal. In any moment, we are all evolving and changing in response to each other, in ways that are completely unpredictable because they are based on responding to each other and directly relating to each other, not based on brute behavior that could be predetermined. God, perhaps, is a part of this process, intimately connected and relating, evolving, as it were, while at the same time being a yet higher form of consciousness. There’s a theological virtue in this, I think, a certain value that transcends the ability to control, to predetermine or foresee the future.

I’ve always been intrigued by theologies that emphasize the openness of the world and of human choice. Process Theology as well as Open Theology are two of the more radical schools of thought. Life is a matrix of ever-changing relationships where we as Christians seek to love, and we strive to understand more deeply what love means as relationships and events change. It is the process, not the goal. In any moment, we are all evolving and changing in response to each other, in ways that are completely unpredictable because they are based on responding to each other and directly relating to each other, not based on brute behavior that could be predetermined. God, perhaps, is a part of this process, intimately connected and relating, evolving, as it were, while at the same time being a yet higher form of consciousness. There’s a theological virtue in this, I think, a certain value that transcends the ability to control, to predetermine or foresee the future.

There’s an old seminary joke about a student who sits down to take an exam. The student finds that there is only one question, a bewildering essay question that goes as follows: Define God and give three examples.

I don’t try to define God. It’s a task fraught with difficulties and unforeseen consequences, both theologically and spiritually. Even defining God based on what God is not (“apophatic” or “negative” theology) winds up with many (if not all) of the same problems. Nonetheless, we tend to have conceptions and perceptions about who God is.

“Who is it that I love,” asked Saint Augustine, “when I love my God?” It’s a question without an answer. Nonetheless, we do answer it — we must answer it. Yet we know that our answers will always fail. Even so, the question matters, or, to be more precise, the questioning matters, the process matters, the process of asking matters, even if the answers will forever elude us.

“I’m yours,” Samantha tells Theodore at one point, “and I’m not yours.” It’s a paradox of love, perhaps, one that Theodore has a tough time coming to grips with. Theodore’s friend Amy is also struggling to come to grips with a relationship. “Falling in love,” she says, “is socially acceptable insanity.”