Politicians, journalists and experts rarely agree, but they have all named the current opioid situation a plague. It’s an appropriate word, with historical and biblical connotations; in every generation, our country has been marred by the misapplication of drugs. Morphine after the Civil War, opium in the late 1800s, cocaine in the 1900s, amphetamines in the 1950s: it’s always a swirl of responsibility, corporate and individual sin that includes the government, health care providers, and users. When those users are predominantly black, it is typically not classified a crisis until far too late.*

A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich is set in the heroin epidemic of the late ‘60s and ‘70s, specifically, in L.A. Of course, drug addiction is not actually about drugs, or addiction, and neither is the film. Hero is about the internalization of messages sent from all sorts of sources, all around, and how they are externalized. As one character in the film observes, “We have been taught to destroy ourselves.”

Heavier Than Anybody Else

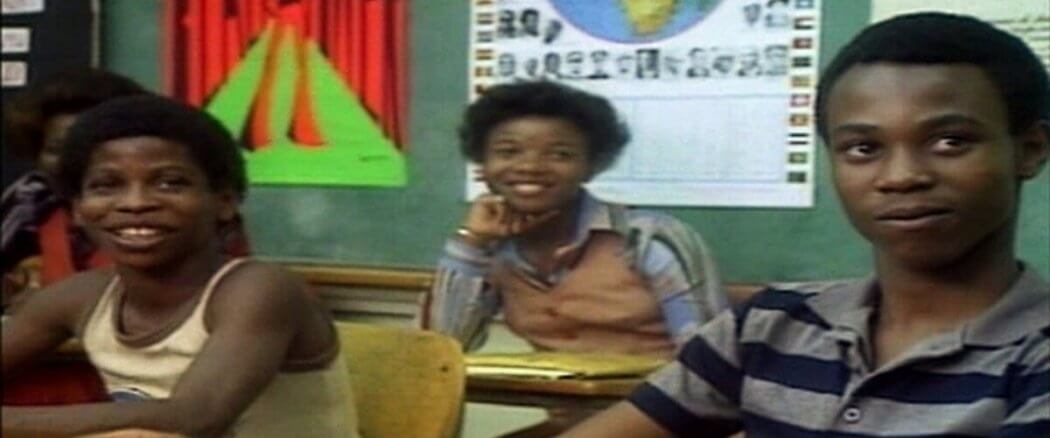

Hero is adapted by Alice Childress from her award-winning, banned, and protested novel, “a merciless yet compassionate examination of how the world has failed a thirteen-year-old heroin addict named Benjie.”** A smart kid who is “always tryna be heavier than anybody else,” Benjie (Larry B. Scott) lives with his mother, Sweets (Cicely Tyson), stepfather, Butler (Paul Winfield) and grandmother, Mrs. Bell (Helen Martin). In an inspired scene, Childress perfectly outlines the family dynamics when Butler starts with the pretense of teaching Benjie a card game and ends with a description of them and Sweets as “two jackasses and a lady.” This is, ultimately, Hero’s central relationship: a stepfather and son, and the father between them, who is not there.

That space has to be filled, and Benjie seeks a whole crowd for it. But to secure them, he must “yield to the machismo initiation rites of the street: he must accept all dares, participate in the drug culture [and] resist parental and legal authority.*** In an early sequence, Benjie, high for the first time, rails against this authority: “down with so-called stepfathers…so-called school, so-called teachers.” Behind him, a sign advises, “Injoy today tomorrow goin’ be worse.”

Parts Never Cohere

“I was very impressed by the film Rashomon…[The] characters tell their stories. Each one’s version is reenacted within the film. But all were lying except one…I do an opposite thing,” elaborates Childress. “In my writing, all the stories differ, but I see that you can get ten different stories out of people all telling the truth. We don’t all view things the same way, each perspective is different.”****

Hero reads like a series of interrelated monologues: the viewpoints change, but the results of prejudice stay the same. In translating the novel to the screen, Childress admirably retains this range of perspectives, and though one reviewer insists that “the parts never cohere,”***** I would argue they confront each other, in the way a complex ensemble drama should. Those parts all speak, from whence they came.

Start Where You Are

One of the film’s first shots is focused on a George Washington Carver quote on a school wall: “Start where you are with what you have; make something of it; never be satisfied.” Two of Benjie’s teachers, Nigeria (Glynn Turman) and Cohen (David Groh), black and white, argue about what would today be called “identity politics,” but Childress’ dialogue is so sharp that by the end of the scene we recognize everyone has an identity, it’s only a question of whose are given priority.

Nigeria teaches African history, emphasizing their royal lineage, and announces, “we got nothing but great people in here.” Cohen requires Benjie to read his essay aloud, then follows it with the statement: “You could become somebody.” Benjie looks up and remarks, “I’m somebody right now.” The excellence of Larry B. Scott’s delivery, though, is that you’re not sure if Benjie is mouthing off, or making a statement of divine worth, or something between.

Nigeria teaches African history, emphasizing their royal lineage, and announces, “we got nothing but great people in here.” Cohen requires Benjie to read his essay aloud, then follows it with the statement: “You could become somebody.” Benjie looks up and remarks, “I’m somebody right now.” The excellence of Larry B. Scott’s delivery, though, is that you’re not sure if Benjie is mouthing off, or making a statement of divine worth, or something between.

Scott’s performance is the breakout, but he is surrounded by rock-solid actors. Cicely Tyson is legendary for a reason, and she brings searing emotion to the film’s most painful scenes and a dazzling smile to the most joyful ones. She and Paul Winfield were a couple off-screen for a time, and the chemistry is clear. Winfield, as Butler, the stepfather, perhaps contributed some personal experience to the role: “[He] and his two half-brothers and half-sister were raised by his mother, Lois, a union organizer in the garment industry, and his construction worker stepfather. ‘They worked hard to keep me unaware we were deprived,’ [Winfield] remembers, ‘but there was always a financial struggle.’”****** An actor of incredible discipline, Winfield seems to intuit the tone of a scene and simply radiate it. He conveys a man who is trying to take his place in a family, a family that took place before he arrived.

History People

“They changed the ending in the picture. Oh, they changed it here, here, here, and here, so much — and I wrote the screenplay!” Childress proclaimed in an interview. “They were changing meanings. The script was weakened — to make the leads more lovable.”******* It’s true, and it’s also true that, even with the changes, the film was still almost banned. As Nixon waged his war on drugs and black lives, human portrayals such as Childress’ were not only praiseworthy, they were — and are — vital to an incomplete national consciousness.

“History people,” Benjie mutters, in a classroom scene near the beginning of the film. “They did their thing, and they died, or they got run out of town, or killed. Where’s the now people to do things now? We always talkin’ about what’s been, never what is. What the people gonna do?”

__________________________________________

*The facts in this paragraph are from “Today’s Opioid Crisis Shares Chilling Similarities With Past Drug Epidemics” by Mike Stobbe. Chicago Tribune. October 28, 2017.

**“Black and Blue” by Hilton Als. The New Yorker. 10/10/2011, Vol. 87, Issue 31.

***Alice Childress by La Vinia De Lois Jennings. Tewayne Publishers. 1995.

****“Alice Childress” by Katheleen Betsko and Rachel Koenig. Interviews with Contemporary Women Playwrights. William Morrow. 1987.

*****Peter Hanson, Every ‘70s Movie. http://every70smovie.blogspot.com/2015/10/a-hero-aint-nothin-but-sandwich-1978.html

******“From Out Of Watts, Paul Winfield Is The Man Who Would Be ‘King’” by Lois Armstrong. People. 02/13/1978, Vol. 9, Issue 6.

******* The Playwright’s Art: Conversations with Contemporary American Dramatists. Edited by Jackson R. Bryer. Rutgers Press. 1995.