“‘You don’t get the point,’ he wanted to explain; ‘the picture you see doesn’t consist of the things you see and say words about. There is something else, something you don’t see at all, something you aren’t intended to see. Look at this one over here, by the door here, where the light from the window falls on it. The dark spot by the road that you might not notice at all is, you see, the beginning of everything.'” – from “Loneliness,” Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson

After I wrote my first review for Cinema Faith, the site’s editor and I began a discussion of how I was going to rate the movie. Stars? Grades? Grades frightened me. What’s a “B” directing performance? How is it not an “A” performance? What’s “C” sound design? What would make it a “C+”?

Besides…if the film was made, even if it was Ernest Goes To Camp, if a film was shot, lit, and acted and edited and music chosen and sound mixed and marketing done and distribution arranged – do we give that an “F”? I think the difference between those who make things and those who do not is a letter grade in itself. Everyone has a script idea. The difference is, Jim Varney made a movie with his.

The Artist and the Critic

As an independent filmmaker, it’s difficult to grade since I can imagine the grades people give my work, a la Matthew 7:2. One of my friends approached me after the first season of my web series to comment, “Imagine if that entire season was done with real actors!” he commented (he thought) helpfully and enthusiastically.

As an artist you feel a great deal like Enoch, the central character quoted above in one part of Sherwood Anderson’s masterwork Winesburg, Ohio. Defensive, whiny, arrogant – but perhaps right after all. “Didn’t you see?” I’d ask, “how the main character in the series wore a class ring on his right hand? Did you notice how he’d refer to it as he played his part?” “Didn’t you notice,” I’d posit to my short film’s audience, “how the character and his right hand man ran after the lost daughter? THE RIGHT HAND MAN IS THE CHURCH.”

As an artist you feel a great deal like Enoch, the central character quoted above in one part of Sherwood Anderson’s masterwork Winesburg, Ohio. Defensive, whiny, arrogant – but perhaps right after all. “Didn’t you see?” I’d ask, “how the main character in the series wore a class ring on his right hand? Did you notice how he’d refer to it as he played his part?” “Didn’t you notice,” I’d posit to my short film’s audience, “how the character and his right hand man ran after the lost daughter? THE RIGHT HAND MAN IS THE CHURCH.”

The answer is – no. No one saw it, and that thoughtfulness and depth were missed. There are plenty of critics (including me) who’d maintain that if something is missed, then it’s the artist’s fault. I’d argue (notice how I’m arguing with myself) that unless we approach art with appropriate thoughtfulness and openness to the artist’s intentions, we end up commenting on silly things without pondering what the artist was trying to say, let alone said.

Seeing the Beauty

Which takes me to my comments on Ex Machina. Because, I see.

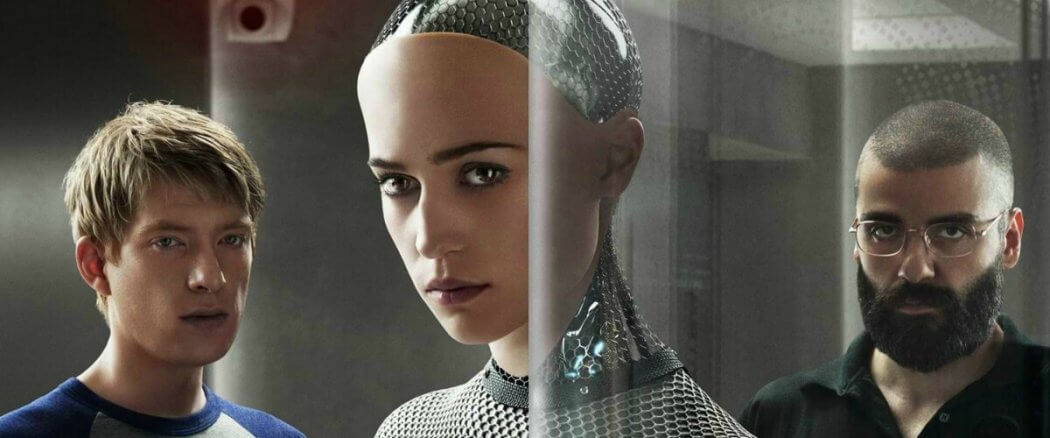

I see that this is a film worthy of comparison to 2001: A Space Odyssey; a film whose director begs comparison to Kurosawa with his geometric blocking and direction. (“Didn’t you see?” I imagine director Alex Garland asking, “how the camera was the third point of the triangle?” Yes.)

Lensed exquisitely by Rob Hard, Ex Machina is one of those magnificent works where you can turn the sound down and just enjoy the beauty. Frame by frame, every scene is lavishly and beautifully composed. Alex Garland and Hard are able to create a world that is claustrophobic, distant, foreboding, and extremely personal all at once.

The writing should be anthologized. By bottling characters into a mountain fortress (laboratory? dungeon?), Garland builds tension, wonder, and deep spiritual thoughts. I found the film challenging me to explore my own deep paranoid dreams. How many times do we (literally or metaphorically) dig a knife into our own flesh to ensure we are truly human?

A Modern-Day Babel

Built around the concept of the Turing test (yes, that Alan Turing) the film’s plot explores how technology is a modern-day Babel.

Nathan: “Yeah, that’s right, Caleb. You got it. Because if the test is passed, you are dead center of the greatest scientific event in the history of man.”

Caleb: “If you’ve created a conscious machine, it’s not the history of man. That’s the history of gods.”

Nathan is an extraordinarily smart and wealthy owner and CEO of a Google-Facebook type of monolithic tech company. Under the guise of a contest, Nathan selects Caleb, a programmer at his company, to join him at his home for a week. Once Caleb arrives, Nathan explains that Caleb will participate in a ground-breaking Turing experiment, evaluating the artificial intelligence Caleb has been developing.

Nathan is an extraordinarily smart and wealthy owner and CEO of a Google-Facebook type of monolithic tech company. Under the guise of a contest, Nathan selects Caleb, a programmer at his company, to join him at his home for a week. Once Caleb arrives, Nathan explains that Caleb will participate in a ground-breaking Turing experiment, evaluating the artificial intelligence Caleb has been developing.

What follows is a study of what makes us human, what moves us to trust one another, what we think is the essence of being a human, the fine line between manipulation and emotion, and the massive flaw of our Tower of Babel (spoiler alert: we forgot that love is what moved God first, moves his creative mind, and what moves Him now) (*yes, it’s pretty sick that we forgot that, but we forget it every day, and I’m a lot worse at it than most everyone).

Outstanding Actors

We need to have a talk about Oscar Isaac. In the last few years, his career has undertaken the stealthiest ascent to one of the best actors alive. In Show Me A Hero and Inside Llewyn Davis, and now as Nathan in Ex Machina, he’s communicating dynamism, frailty, power, anger in a way we’ve seen only a few times before. We haven’t seen the last of him, and that’s a good thing. His Nathan is charismatic, disturbing, and could not have been played by anyone else.

Domnhall Gleason creates the extraordinarily human, thoughtful, trusting, and confused center this film needs to succeed. In the hands of a lesser actor, the film’s brilliance would have played as cold and antiseptic science fiction, but here we see someone wrestling with his troubled past, wondering at one point if he himself is the artificial intelligence in the test. The entire film feels like a beautifully-shot Arthur Miller play, and Gleason is Loman.

Gleason’s resume in the past few years is sneaky great. The underrated About Time, Harry Potter, Star Wars (with Isaac), The Revenant, Brooklyn, Unbroken – did he get all the parts available? I would argue that the most underrated quality of an actor – by far – is choosing parts. Gleason has found them, and they’ve found him back. He’s another stealth talent who’ll likely be holding some golden statue aloft in the next few years.

Forget the Grade

No grade here. Just see Ex Machina. There’s a lot to appreciate, and even more to explore, ponder, and admire. A beautiful piece of art unlike anything I’ve seen.