There are many creative forces which go into storytelling through film. You may not always be fully conscious of everything being used to communicate a story to you. The easiest element to recognize in a film is the on-screen performers. Film actors are the stars. They get paid the big bucks. Everyone talks about them, even people who may not have any interest in film. They’re the ones whose images are shining onto the screen in an otherwise dark theater.

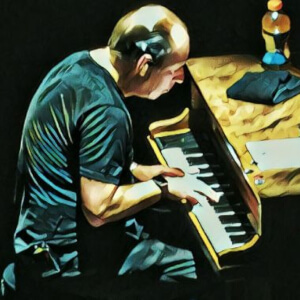

I don’t mean to undermine the great art of screen acting. But there is an equally significant element of filmmaking that goes unnoticed, and remains one of my favorite pieces of the medium. As the lights flicker on the screen, these artists perform in the dark, filling the aural space and telling you a story with raw emotion. These artists are known as Film Score Composers. They work best when they are unseen. If they step too far in the spotlight, the illusion is lost. However, in this article we’re going to shine the spotlight directly upon one of these artists in particular; arguably the most influential film composer of our day: Hans Zimmer.

Brewing a Dream

Hans grew up in a small German village without much access to film or television. One day he sneaked into a cinema that happened to be playing Once Upon a Time in the West. The marriage of Sergio Leone’s visuals with the great Ennio Morricone music left a long-lasting impression on him that directly influences his music to this day. Throughout his adolescence, he taught himself piano and music theory, rejecting formal methods of training, and made his way through the world of 80s pop music, including working with The Buggles and even appearing in their pivotal music video, Video Killed the Radio Star. Interestingly enough, though, he found pop music to be too constrictive. It was too easy to get pigeonholed into a genre. Despite the pop music industry’s projection of artistic freedom, Zimmer wasn’t comfortable, so he moved on to film music, getting an internship at the studio of composer Stanley Myers, composer of films such as The Deer Hunter and The Witches. Hans’ job responsibilities mainly entailed making the coffee; an asset for people whose career it is to sit at a keyboard and bang out notes all day and night. This seemingly meager position gave Hans a front row vantage point on the film composer’s process. One day, Myers and his team were struggling with a cue, and Hans made the bold move of speaking up to make a suggestion. They tested his suggestion, and in Hans’ words, “I didn’t make a lot of coffee after that.”

The typical Zimmer sound is bombastic, passionate, robust, heavy on brass, synths, and big booming percussion. However, his themes are often distinctly minimalist by design. Two notes are all he needs to make Nolan’s take on Batman resonate, but those two notes are blasted long and loud. For the score to Chris Nolan’s Interstellar, the director played to Zimmer’s strengths, and had him write the film’s theme before production even began. He sent him a fable about a father and son, and asked him to write whatever came to him. In Zimmer’s online Master Class, he describes that Nolan “cleverly steered it in a way that it automatically made me think of my relationship with my son. So I wrote him this tiny, very personal theme.” It was only after Zimmer wrote the theme that Nolan revealed to him that the film was also a space epic, but now with the theme, they had the heart of the score from which to build upon. The Zimmer sound has become the standard style for most big blockbuster scores. Some might even call him the death of film music as we know it.

The typical Zimmer sound is bombastic, passionate, robust, heavy on brass, synths, and big booming percussion. However, his themes are often distinctly minimalist by design. Two notes are all he needs to make Nolan’s take on Batman resonate, but those two notes are blasted long and loud. For the score to Chris Nolan’s Interstellar, the director played to Zimmer’s strengths, and had him write the film’s theme before production even began. He sent him a fable about a father and son, and asked him to write whatever came to him. In Zimmer’s online Master Class, he describes that Nolan “cleverly steered it in a way that it automatically made me think of my relationship with my son. So I wrote him this tiny, very personal theme.” It was only after Zimmer wrote the theme that Nolan revealed to him that the film was also a space epic, but now with the theme, they had the heart of the score from which to build upon. The Zimmer sound has become the standard style for most big blockbuster scores. Some might even call him the death of film music as we know it.

Beyond “Bwaum”

When people talk of Zimmer, they usually mention Pirates of the Caribbean, The Lion King, and everything he’s ever done for Christopher Nolan. What many folks don’t realize is that Zimmer is one of the most versatile film composers of all time. He’s done his fair share of epic action dramas, but he’s also done a decent amount of romantic comedies and animated films, and has dabbled in instruments and styles of all kinds, from The Prince of Egypt to The Boss Baby. And contrary to popular belief, he does not frequently use a “bwaum” sound in his music. Someone needs to take that off his IMDB page already. Only Inception, as far as I can discern, utilized that sound, and not even to the effect that people think it was used. The trailer for the film popularized that sound more than the movie or its score ever did, and Zimmer didn’t even compose that. It’s one of those Mandela effect things, like how Hannibal Lecter never said “Hello, Clarice” in Silence of the Lambs.

Jolly German

Film composers are finally becoming recognized for the work they do nowadays more than in years past, when they remained these mysterious names on soundtrack covers. Zimmer has come out with a treasure trove of interviews, concerts, and, as mentioned, a Master Class and thus has demystified himself a bit, at least in my mind.

“Make sure that you are entertained. It’s not about playing to the gallery. Check with yourself that the stuff you’re doing actually gets you excited and people will follow along. If it’s a compelling idea, people will support you in it.”

Zimmer is a human who puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you and me, but he is a very jolly, passionate, and idiosyncratic human. He speaks in a German/English accent with a distinct lisp and seems to simultaneously love and hate talking about himself. He pauses in the middle of one of his Master Class lessons to remark “This is supposed to be called ‘Master Class’ as opposed to ‘Disaster Class.’” It’s easy to see why so many people, filmmakers, musicians and composers alike, love working with him. You get the sense that he’s being genuine with you no matter what he’s expressing, whether he’s succeeding in communicating clearly or not. Someone at his level of success — a degree of recognizability only matched by John Williams in the realm of film music — might fall into pompousness, but he retains a humble curiosity. It’s part of his life philosophy to be both ambitious and modest. He muses, “All I know is people that I come across that do great work are the people that ask the most questions. And they’re by nature inquisitive.” And that’s the lifestyle he seems to try and exude. He avoids coming off as the guy in the room who views himself as above everyone else. Hearing him talk about his work never ceases to inspire me, and I highly recommend it to any creative person out there.

Personal Favorites

And here’s the part where I geek out.

This is not a definitive list of Hans’s career highlights, but they’re the scores of his that have resonated the most with me. Listed below are my favorite Zimmer scores with my favorite tracks also listed. If I can’t pick a favorite track, it’s because the whole score flows together seamlessly to where it’s hard to distinguish one piece from the next. The whole album is my favorite track.

Interstellar (2014) — A sheer masterpiece. This score exemplifies Hans’ inventiveness. For this, his 6th collaboration with Christopher Nolan (including working with Nolan as producer on Man of Steel), Zimmer decided to defy expectations by locking away all his massive drums and replaced their sound with a giant organ from an old London church. It’s one of his most transcendent, grandiose, yet intimate scores he’s ever done, which is really saying something. (No favorites)

Sherlock Holmes 1 & 2 (2009 & 2011) — A couple of fantastically original scores, filled with manic fiddles, dulcimers, banjos, and a broken piano purchased specifically for the score. For the second film, which involved European Gypsies (also known as the Roma) in its plot. Zimmer studied Roma folk music by visiting 7 small European villages, according to an article for The Hollywood Reporter. He recorded 13 musicians from those villages for the score, and a portion of the score album’s proceeds went to help pay for basic necessities of the impoverished people he met. (Favorites: “Marital Sabotage,” “Is It Poison, Nanny?,” “Shadows,” “It’s So Overt It’s Covert,” “The End?”)

Sherlock Holmes 1 & 2 (2009 & 2011) — A couple of fantastically original scores, filled with manic fiddles, dulcimers, banjos, and a broken piano purchased specifically for the score. For the second film, which involved European Gypsies (also known as the Roma) in its plot. Zimmer studied Roma folk music by visiting 7 small European villages, according to an article for The Hollywood Reporter. He recorded 13 musicians from those villages for the score, and a portion of the score album’s proceeds went to help pay for basic necessities of the impoverished people he met. (Favorites: “Marital Sabotage,” “Is It Poison, Nanny?,” “Shadows,” “It’s So Overt It’s Covert,” “The End?”)

Pirates of the Caribbean 2 & 3 (2006 & 2007) — Zimmer was not credited for the first iconic score, but only because it was a group mad-dash to get a score done at the eleventh hour after Alan Silvestri’s score was rejected. In the sequels, Zimmer officially takes the helm and expands beautifully on what has become the new standard for all pirate scores to come. I have a particular soft spot for the the 3rd score. The new themes add a rich operatic quality to the mix, and Zimmer takes his opportunity to give a couple nods to Morricone with a western standoff in “Parlay,” and an oboe solo in “I See Dead People in Boats” (in the style of The Mission). (Favorites: “Jack Sparrow,” “The Kraken,” “I Don’t Think Now is the Best Time,” “At Wit’s End”)

Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002) — The score that introduced me to Zimmer and it still holds up to this day. (No favorites)

The Prince of Egypt (1998) — Masterpiece musical soundtrack that provides a roller coaster of emotions from jubilant to mournful, tranquil to intense. (No favorites)

“We’re compelled to tell the fable of our existence; of our human journey or whatever. And I think, when we run out of words. And when we run out of beautiful pictures. We have to resort to this other language called music. And I’m not trying to be profound…but when you spend a little bit of time thinking about it, you can actually express some fairly good things about the human condition in notes that you might not be able to express quite as brilliantly in words.”

Spanglish (2004) — Highly underrated score. Here’s an example of how a score can often tell the film’s story better than the film did. Zimmer mixes classical hispanic guitars with a peppy orchestra that combine to convey a subtle but potent sense of longing. The two main themes are revisited very creatively in this. (No favorites)

Angels & Demons (2009) — A crazy, no-holds-barred piece of epicness that sounds like it belongs to a much more exciting film than it does. (Favorites: “160 BPM,” “503”)

Madagascar 1, 2, & 3 (2005, 2008, & 2012) — Hans made a brilliant theme in the first one and expanded upon it in fun ways in the sequels (Favorites: “Zoosters Breakout,” “Once Upon a Time in Africa,” “Rescue Me,” “Game On,” “Light the Hoop on Fire!”)

Regarding Henry (1991) — This score just gives me a warm feeling. It may be a little saccharine at times, but it’s cozy and uplifting and it features Bobby McFerrin vocals. (No favorites)

Kung Fu Panda 1 & 2 (2008 & 2011) — These are among my favorite scores of all time, but they have so much influence from Zimmer’s co-composer, John Powell, that it’s hard for me to attribute the majority of their brilliance to Zimmer, but Powell is a rant for another article. (No favorites)

Coda

Congratulations, you’ve made it to the end! I hope you enjoyed reading and learned something about Hans Zimmer, or film music in general, that you didn’t know before. Tune in next time as shine the spotlight over to the great John Williams.

__________________________________________

Hans Zimmer Teaches Film Scoring: https://www.masterclass.com/classes/hans-zimmer-teaches-film-scoring/enrolled

How ‘Sherlock Holmes’ Turned Hans Zimmer on to the Roma Cause: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/hans-zimmer-sherlock-holmes-roma-gypsies-275467