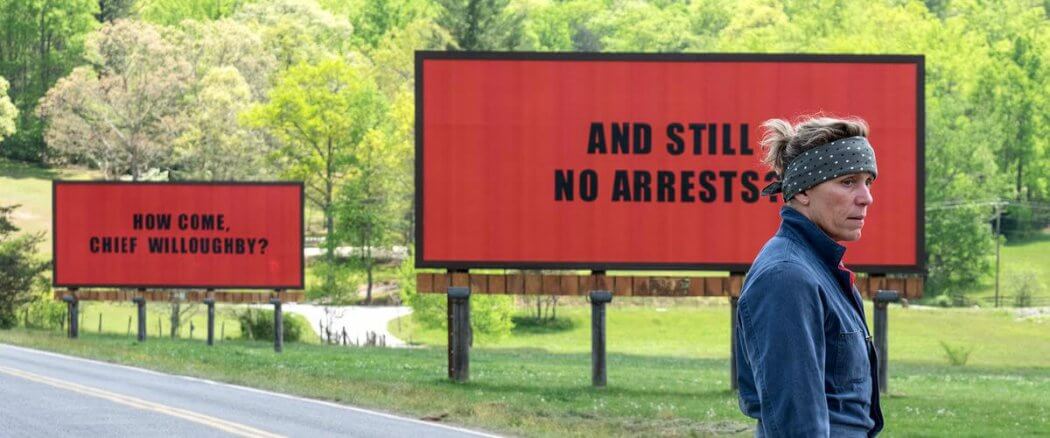

As the title states, there are 3 billboards outside the fictional town of Ebbing, Missouri. They work in concert with each other, the blood red background and white lettering impossible to miss amongst the greens and grays of the hilly terrain. Each has its own distinct message, but only one stokes the ire of the town. And it’s the first one we see toward the beginning of Martin McDonagh’s Midwestern dark comedy.

One of the calling cards of the movie is the portrayal of small town life. There’s one town square with the advertising company, the police station, and all the town’s foot traffic. There are also the houses on the outskirts of the downtown area and the small knick-knack shop down by the railroad tracks. But the real signature piece of the puzzle that brings Ebbing to life is the relationships. You don’t need to have lived in a rural town to know that once the population dips below a certain level, everyone starts to know everyone.

That’s what makes the first — and final, really — billboard the focus of our attention. It singles out a man that everyone knows. It’s not just that he’s the police chief or a husband and father. He’s Bill Willoughby, the guy who employs troubled men and raises horses out at his family farm. As Three Billboards progresses, we get to know him as if we were part of the town ourselves.

Characters and the relationships between them are the driving force behind McDonagh’s film, but its grief that really takes the main stage. Watching that grief play out in various people and situations makes Three Billboards one of the year’s most captivating and uncomfortable movies.

‘You’re Culpable’

A lot of the talk surrounding Three Billboards has been centered on the film’s protagonist, Mildred Hayes. She’s a “tough old boot” written in the same mold as many of the great antiheros of 21st century television and film. And what truly makes Hayes special is a career-best performance from Frances McDormand, a true artist all too often forgotten in the rotating grain mill of young starlets. And from the start, McDonagh wisely uses the billboards as a pseudo-McGuffin, framing the characters interactions and development around the reaction to the billboards and the consequences that follow.

The real treat behind all of those interactions is the complexity McDormand gives all of Hayes relationships. Her core characteristics are there from start to finish: rage, suspicion, regret. But she also builds in unsaid backstories behind each supporting character. Whether it’s Willoughby, her son, or even the advertising employee who helps her put the billboards up: there’s a different touch of humanity in every scene, sometimes more generous and sometimes more villainous. To be sure, Hayes’ most reprehensible moments feel grounded by a sense of righteous justice, but the overall picture we get of her is considerably more interesting than saint or sinner.

The real treat behind all of those interactions is the complexity McDormand gives all of Hayes relationships. Her core characteristics are there from start to finish: rage, suspicion, regret. But she also builds in unsaid backstories behind each supporting character. Whether it’s Willoughby, her son, or even the advertising employee who helps her put the billboards up: there’s a different touch of humanity in every scene, sometimes more generous and sometimes more villainous. To be sure, Hayes’ most reprehensible moments feel grounded by a sense of righteous justice, but the overall picture we get of her is considerably more interesting than saint or sinner.

For instance, there’s a scene where Hayes confronts the town priest when he comes calling about the billboards. After an indirect chiding about her absence at church, Hayes discusses culpability with him, invoking Los Angeles gangs and the less subtle example of sex scandals within the Catholic church. It’s a quick scene, but one that stands out on further examination. The question of culpability is one that’s central to McDormand’s portrayal of Mildred. More specifically: who owns responsibility in the death of her daughter? McDonagh show us that she blames everyone, including herself, at least a little bit.

How Are We Redeemed?

Branching off the question of culpability in Three Billboards is that of redemption. And if Mildred Hayes makes us ponder the former, Officer Jason Dixon is the vessel of the latter. Our first introductions to Dixon aren’t kind. His proclivities toward alcohol and boorish racism make him a perfectly heinous person. The fact he’s found favor in the seemingly decent Chief Willoughby is confusing. Throughout the film’s first half, we hear talk of how Willoughby sees Dixon as a good man at heart. And before we ever get a chance to believe him, out flies a racial slur or homophobic comment. One thing we never question, though, is Dixon’s loyalty. And it’s this loyalty that sparks his move toward that redemption mentioned above.

It’s tricky to write about this turn as it involves some pretty major plot points. But it’s not hard to see how Dixon works to redeem himself once the turn happens. For every seen and unseen bad deed, he seeks to do a good deed. Some are acted on and some are spoken, but Dixon’s journey to make peace with his surroundings is one of the more hopeful parts of a film that seeks to find scraps of light within the darkness.

It’s tricky to write about this turn as it involves some pretty major plot points. But it’s not hard to see how Dixon works to redeem himself once the turn happens. For every seen and unseen bad deed, he seeks to do a good deed. Some are acted on and some are spoken, but Dixon’s journey to make peace with his surroundings is one of the more hopeful parts of a film that seeks to find scraps of light within the darkness.

But in Dixon’s story we also see how futile these good deeds can be. Many of his efforts fall short of fulfilling their goals and there’s no evidence some burnt bridges are ever rebuilt. Some would chalk this up to universal meaninglessness. But I would tend to call it, “works righteousness.” And — again without spoilers — I’ll say instead of his own deeds, Dixon is ultimately “redeemed” by other people.

‘Those Billboards Ain’t Gonna Bring Her Back’

While Mildred Hayes and Officer Dixon carry the load between responsibility and redemption throughout Three Billboards, there’s one overlying theme that carries more weight than almost anything else: grief. In the promotional interviews for Three Billboards, McDormand has been prone to point out that grief is the heart of the film. And while we tend to think of grief as a process or series of steps, McDonagh is as concerned with moving on as he is with the feeling itself.

For every person who’s ever experienced grief of any sort, you know how weighty it is. It’s a burden you carry with you until you’re ready to let it go… or just learn how to live with it. For many of Three Billboard’s characters, it’s the latter. Almost every person in the film deals with grief on some level. When you’re part of a small town, you don’t get to hide from the fallout of tragic events. And while we do see these people in the different stages of the grief process, no one ever really seems to move on.

That may sound hopeless, but McDonagh’s writing does a good job of lifting the shroud ever so slightly as 2 hours pass. We see how life moves on for the people of Ebbing. And more importantly, we see how relationships form and develop, even when the circumstances don’t. The central question, at times, seems to be to be, “How do we bear our burdens well?” And while Three Billboards is unquestionably dark, we see appropriate responses to inappropriate methods. Violence is often met with consequence and those who close themselves off to help are often left lonelier than they were before.

That may sound hopeless, but McDonagh’s writing does a good job of lifting the shroud ever so slightly as 2 hours pass. We see how life moves on for the people of Ebbing. And more importantly, we see how relationships form and develop, even when the circumstances don’t. The central question, at times, seems to be to be, “How do we bear our burdens well?” And while Three Billboards is unquestionably dark, we see appropriate responses to inappropriate methods. Violence is often met with consequence and those who close themselves off to help are often left lonelier than they were before.

Learning how to grieve is a process, and a messy one at that. Fortunately, McDonagh finds meaning in forgiveness. One scene represents this well, though it needs to be addressed in vague terms. While one character lies incapacitated in the hospital, they’re confronted by a person they’ve severely wronged. The act itself is presented in brutal, graphic detail earlier in the film. And faced with the opportunity to enact some sort of revenge — or ignore them altogether — the wronged party responds with a simple measure of kindness. It’s not the only example of forgiveness as the film moves toward its resolution, but it’s undoubtedly the most concentrated one.

‘Right Now, There Ain’t Too Much More We Can Do’

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri isn’t about the actual billboards. They are a helpful reference point, both thematically and visually. Some of the film’s most powerful moments happen at the billboards themselves. And some of the best dialogue is centered around the thought behind the message they portray. But really, it’s about humans learning to live with the past and each other at the same time. Ebbing, Missouri might not be a real place, but its people and their relationships feel genuine in light of the circumstances with which they’re faced.

I understand that a lot of this review wasn’t technical, but I’m not sure the technicality is what makes it so good. It’s a simple film that is both shot and written beautifully, and the director brings spectacular performances from the entire cast. The story isn’t wildly creative or different, at least not from any other small-town, folksy film you’ve ever seen.

What does make it special, however, is the way we’re forced to confront feelings and conflicts we often choose not to. Grief, forgiveness, anger, regret — they’re all intense and hard to bear. Personally, when I find myself experiencing any of them, my tendency is to deflect and distract. But in Three Billboards, Martin McDonagh has crafted a story that makes us experience those feelings in very real ways. We see both the interactions that lead to tragedy and the hopelessness that comes from a lack of resolution of said tragedy. But most importantly, we’re injected into a world where grief doesn’t go away; you just have to learn how to live with it. And until a day where all tears are wiped away, that’s a reality in which we all might eventually find ourselves. Three Billboards gives us a roadmap of that reality that acknowledges its truths while holding onto the hope that maybe one day we might get the respite we desire.