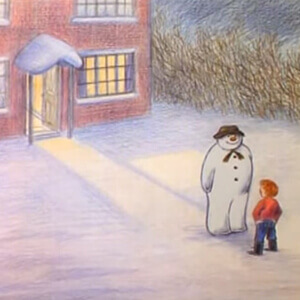

Sometimes a film is good because of when we see it and sometimes because it’s just good; The Snowman is both. I can’t pinpoint the first viewing, but I was very young and it was totally overwhelming, in the way a piece of art is when it matches a piece of you. It was nearly an exact match, as I shared the main characteristics of the child in the story: a redhead, captivated by imagination, living in the country and in love with winter. More than that, it was the feeling, a tremendous current through the film, which seemed the externalization of so much inside.

“[The Snowman] is a simple, wordless masterpiece…” Executive producer Iaian Harvey describes the eponymous book upon which the film is based, but could easily be speaking of the latter. “[There’s a] wonderful sweep of the illustrations that…break out from the smaller ones, as you build up the story, to, suddenly, the relief as the snowman and the boy take off and fly, and then we end up with double-page spreads, which just, allow Raymond [Briggs] to express all of his emotions through the imagery.”* As with any excellent film adaptation of a book, there is the additional relief of something precious being transmuted into another version of itself, with such incredible care.

I Made the Snowman

“I remember that winter because it brought the heaviest snow that I had ever seen,” Briggs says in the scene that opens The Snowman, which contains the only words — and live action — in the film. The footage is of Briggs himself, tromping through a brown countryside, the branches of bare trees like bony fingers, holding up the clouds, lit from behind. “The snow had fallen steadily all night long, and in the morning I awoke in a  room filled with light and silence. The whole world seemed to be held in a dreamlike stillness. It was a magical day, and it was on that day I made the snowman.”

room filled with light and silence. The whole world seemed to be held in a dreamlike stillness. It was a magical day, and it was on that day I made the snowman.”

To describe much more of the story would be like listing the ingredients for a peanut butter and jelly sandwich — reductive, and minimizing its proven appeal. The Snowman is popular in the U.S., but it’s omnipresent in England and Japan and has made a cultural impact on many other countries as well. Adapted as a full-length ballet and a musical stage production, both are performed all over the world. “It’s become a huge commercial phenomenon,” Briggs admitted, almost incredulous, in an interview at his alma mater. “It’s extraordinary…you feel, it’s not really me…who is this person they’re talking about?”**

Retaining and Refracting

Shortly after the book was published, John Coates, of TVC, the U.K.’s longest established animation studio, sensed its cinematic possibilities. “I got two of my assistant animators…Joanna Harrison and Hillary Audus,” he recalls, “to go and buy a dozen copies of the book, start cutting it up, start putting it under the camera, to make a little [demo  animation].” This technique, so attentive to the drawing style of the book, continued, in one form or another, throughout production, creating “a handmade look that we’re missing nowadays.”***

animation].” This technique, so attentive to the drawing style of the book, continued, in one form or another, throughout production, creating “a handmade look that we’re missing nowadays.”***

Indeed, Harrison and Audus, along with director Dianne Jackson, were vital to the book’s conversion to screen, retaining its qualities and refracting them. The former were two of eight animators assigned different sequences of the film, and each personally connected to it, evidenced in all sorts of intimate ways: Audus changed the car to a motorcycle because she was active in cycling at the time; the very name of the lead, unknown in the book, was taken from Harrison’s boyfriend who later became her husband. Roger Mainwood, another animator, recollects watching early line tests with Jackson and experiencing “the tingle factor…[we] stopped and looked at each other and said, ‘we’ve got a classic.’”

Innocence, or the Memory of It

A critical component of that classic status – and perhaps the single greatest contribution to The Snowman — is Howard Blake’s score, which floats over and under the film, massive and weightless. “Everything that happens,” Blake insists, “is exactly conveyed and given emotion [and shape] by the music.” From another composer on another project, that might sound egotistical, but here it registers as fact. Months before Blake was approached about The Snowman, its main theme occurred to him while walking on the beach; a haunting melody that, with a few notes, evokes an almost unbearably beautiful innocence, or the memory of it.

Watching The Snowman recently, I was astonished at the craftsmanship, the quality of which, in some ways, I appreciate more now as a struggling artist than as a little child. Even more, though, I’m astonished to find the feeling still there, and bigger than I remembered. Or perhaps it’s my experience that’s deepened?

“You are…above and beyond anything else, a children’s writer, but you didn’t have children yourself…” journalist Jon Snow once commented to Briggs, “and you don’t particularly want to spend any time with them, and yet you are a feast of children’s consumption.” Briggs replied, “Yeah, well, it’s probably me. I mean, all of these things are in yourself, aren’t they, really.” Snow asked, “Are you a child?” And Briggs chuckled, “Everybody is.”****

__________________________________________

*From Snow Business: The Story of The Snowman, 2002, Directed by Rik Lander

**From a 2011 interview by George Blacklock at the Wimbledon College of Art, formerly Wimbledon School of Art, at University of Arts, London

***A quote from Audus in Snow Business

****From a 2012 interview by Jon Snow for Channel 4 News

[NOTE: You can stream The Snowman on various YouTubes. Here’s the original version in SD to get a taste of it. For the full experience we recommend watching it in HD on Amazon Prime or buying the Blu-ray. – Dan]