It seems like every few years there is an animated movie that knocks me off my theater seat. In my life a few of those that astounded me — due to an unusual subject, a new perspective, or an innovative methodology — are Fantasia (1940 — okay I was not alive then but I first saw it in the 60’s on the “Walt Disney Show”), Yellow Submarine (1968), Fritz the Cat (1972), Heavy Metal (1981), Grave of the Fireflies (1988), The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), Princess Mononoke (1997), Waking Life (2001), Sin City (2005), Persepolis (2007), Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), Anomalisa (2015), and last year’s Tower. I am sure you could make your own list.

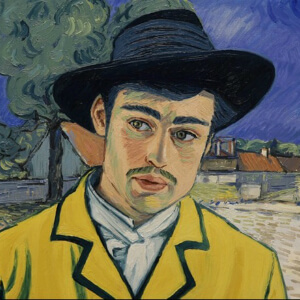

This year the animated film that unexpectedly stunned me was Loving Vincent. This unusual animation (not a child’s feature, not a comic book adaptation, and not Japanese anime/manga) dwells on the last months of Vincent van Gogh’s life and plays out as a mystery as to his cause of death, generally attributed to be a suicide (at age 37). I have seen it described as film noir but it is not that dark in its images or themes. The film’s protagonist is the young ne’er-do-well Armond Roulin (voiced by the relatively unknown Douglas Booth). Armond was in fact a member of the Roulin family, the subjects of a collection of Van Gogh’s paintings. The fictional device that drives the film involves Armond’s father Joseph, the village postman, asking Armond to deliver one of Vincent’s long-set-aside but recently discovered letters. One year after his death, Joseph had found the letter which was addressed to Vincent’s brother Theo, his only relative with whom he had a relationship. His father assigns Armond the task of delivering the letter to challenge him to rise to the task, but numerous complications arise, primary among them that Theo died six months after Vincent. This leads Armond to travel to the French village of Auvers-sur-Oise where Vincent painted so many of his final subjects and landscapes, and where Vincent spent the last weeks of his life. Armond uncovers Van Gogh’s relationships with numerous locals (that he painted) and begins to unravel the many questions that arise as to what actually happened during the days preceding his demise.

A Nonentity, An Eccentric

The film, starting after Vincent’s death, mentions but largely omits many fascinating parts of Van Gogh’s life — his desire to be a priest like his father, his missionary work, his contentious relationship with Paul Gauguin, and his stormy relationship with a prostitute that he lived with but the relationship ended with Vincent mutilating himself and giving his lover a parting gift of his external ear. Instead, the film explores the mystery of why (and if) Vincent, seeming at this stage of his life to be relatively stable and beginning to be lauded for his work, would so violently end his life by shooting himself in the abdomen with a pistol. The questions are many, with contradictory evidence discovered. They remain open to diverse opinions to this day.

This is a story of a tortured man, prone to depression and feelings of worthlessness, who had but a few people in his life he loved and trusted. He wrote “What am I in the eyes of most people — a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person — somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then — even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart.” Did his depression overwhelm him? Did one of those he loved turn their back on him — or even betray him? Did his family’s judgement of his failed life finally vanquish Vincent? Or was his death a tragic accident where he was an unfortunate bystander to a random act?

This is a story of a tortured man, prone to depression and feelings of worthlessness, who had but a few people in his life he loved and trusted. He wrote “What am I in the eyes of most people — a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person — somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then — even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart.” Did his depression overwhelm him? Did one of those he loved turn their back on him — or even betray him? Did his family’s judgement of his failed life finally vanquish Vincent? Or was his death a tragic accident where he was an unfortunate bystander to a random act?

Making It Happen

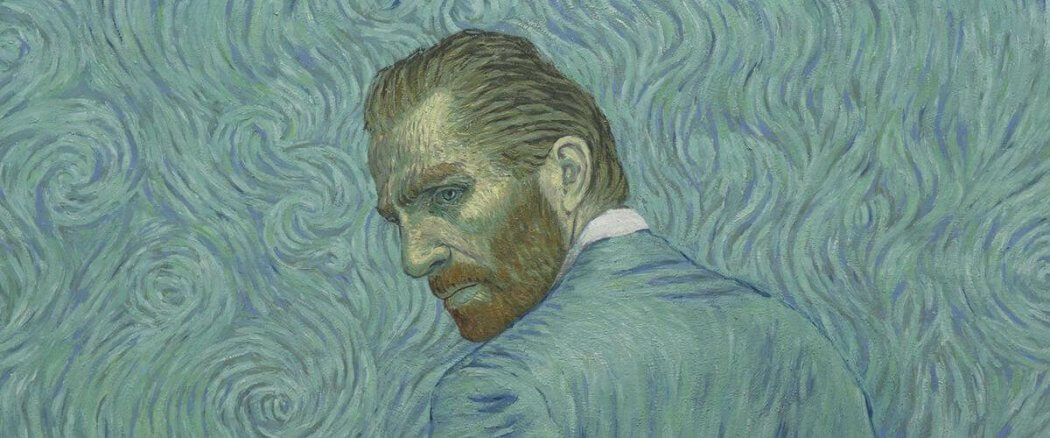

Regardless of the plot, this film is exceptional, not for its murder-mystery narrative but rather its dazzling series of painted images… one of Van Gogh’s very famous portraits or landscapes after another — 125 of his works in total. And they are animated in the most magical of ways. The innovation behind how these images are made to move and flow one into another is nothing short of astounding. In fact, over 65,000 frames were hand painted in oil by the production company’s 125 experienced artists (not animators) from 20 countries. Starting with the actors being posed as in Vincent’s pictures, they were then set to motion against a green screen to transition into the motion representation of the story. The film backgrounds were then composited with Van Gogh scenes. The film was then cut and edited. Finally each separate frame was transferred onto a canvas and the artists then painted over each one. They created the lovely flow of paint which remained so true to Van Gogh’s technique (thick layers of paint mixed with his palette knife through a technique called “impasto”) resulting in the recognizable “Van Gogh” appearance of the entire film.

Of course, there were scenes needed for a cohesive story that Van Gogh never painted and those were innovatively handled by using flashbacks painted in the Van Gogh style but in blacks and greys. They also dealt with their need for night scenes (even though Van Gogh rarely painted nocturnal images) by darkening and shadowing his paintings. Another complication was the fact that Vincent painted on all sizes of canvases (anything he could get his hands on as he was often destitute to the point he could not purchase supplies) and his paintings had markedly different aspect ratios, which had to be worked around. Small wonder that the effort took over four years, despite the army of artists employed (who worked for minimal compensation other than the honor of being involved with such a prestigious project).

A Dream Realized

The entire project, never before successfully attempted for a feature-length film, was the brainchild of classically trained Polish artist Dorota Kobiela. Fascinated by the life of the French impressionist, she at first made a 7-minute animated short using the technique in a rough form. This was in turn seen by English filmmaker Hugh Welchman who convinced her that the story deserved to be a feature-length film with deluxe treatment. Together they scraped for funding, obtaining a grant from the Polish Film Institute as well as funds from a Kickstarter campaign. Upon release, the film has done exceptionally well in Europe (it was BAFTA nominated), other world nations, and in the US winning numerous accolades and nominated for an Academy Award under the category “Best Animated Feature.”

The voice actors we hear are excellent. In addition to Douglas Booth as the lead, they include Saoirse Ronan (Ladybird), Aiden Turner & Eleanor Tomlinson (of Poldark fame), and Helen McCrory (Narcissa Malfoy in the Harry Potter films). There is a variety of accents and some viewers were bothered by that but I was not at all. Despite knowing very little about the art world, the brilliant artwork totally fascinated and engrossed me.

Vincent’s Letters

Vincent van Gogh painted very few self-portraits and wrote little specifically about himself, other than writing hundreds of letters (903 survive), with over 650 of those addressed to his beloved brother Theo. You can learn a lot about a person from their letters — see Paul the Apostle. In large part this film is based on the information from these letters. But considering that we often do not tell — even those to which we are close — everything we are experiencing, this viewpoint may be a selective telling of his last weeks. But Vincent was very introspective in his letters and appeared to entrust Theo with the most intimate of his thoughts and anxieties. (If interested, the filmed 1981 one-man play “Vincent,” with Leonard Nimoy playing Theo van Gogh, features excerpts from many of Vincent’s letters being read by Nimoy and is available without charge for Amazon Prime members. It is informative and tremendously interesting, showing that Nimoy was more than “Spock.”)

Vincent van Gogh painted very few self-portraits and wrote little specifically about himself, other than writing hundreds of letters (903 survive), with over 650 of those addressed to his beloved brother Theo. You can learn a lot about a person from their letters — see Paul the Apostle. In large part this film is based on the information from these letters. But considering that we often do not tell — even those to which we are close — everything we are experiencing, this viewpoint may be a selective telling of his last weeks. But Vincent was very introspective in his letters and appeared to entrust Theo with the most intimate of his thoughts and anxieties. (If interested, the filmed 1981 one-man play “Vincent,” with Leonard Nimoy playing Theo van Gogh, features excerpts from many of Vincent’s letters being read by Nimoy and is available without charge for Amazon Prime members. It is informative and tremendously interesting, showing that Nimoy was more than “Spock.”)

Where Was the Caring Hand?

As a Christ follower, it is discouraging to hear how Vincent, whose heart as a missionary went out to the poor and destitute, was rejected by the church for relating too much to the common laborers. And when he began to manifest his bipolar depression (with periods of mania where he would neglect to eat or sleep working feverishly at his art — as was the case just before his death) one wonders if there was any Christian hand reaching out to help him and care for him as he had tried to care for others. Instead he came to this sad and mysterious demise.

I am an absolute novice when it comes to impressionistic painting, but when I see the animated birds beautifully lifting to wing from his “Wheat Field with Crows,” and I am enraptured by the swirling clouds in his famous “Starry Night,” I know that Vincent was a wonderfully talented child of God. How sad to lose him to earth’s dust at such a young age. As he said in one of his last letters to Theo, “We (artists) cannot speak other than by our paintings.” And in this unique animated film, Vincent once again, with a fresh voice, “speaks” to us.