“Some boomerang, this story,” an inspector observes, in the novella Black Girl by Ousmane Sembéne, which he adapted for film. I won’t reveal the scene of the crime, but the inspector might as well be speaking of Sembéne’s story, and may be, in the way authors often delegate such meta-tasks to the characters. Black Girl is a carved and swift tale that slices into the darkness, and while you are still staring, whips back with stunning force. Critic A.O. Scott describes it as “one of those works of art [that is] powerfully of its moment and permanently contemporary.” It is also art made by a worker who relates to the subject as one of his own.*

“Films with Africans usually would portray them as accompanying somebody or making somebody’s story more plausible,” explains Manthia Diawara, a professor of comparative literature and Africana studies. “Black people just are caricatures. They’re silhouettes. They don’t have interiority.” Black Girl was “the first film from Africa that gave…the black diasphora a sense of some kind of black aesthetic coming out of Africa…this is black womanhood, she has subjectivity, she has character, she is no longer this forlorn maid thrown in some corner.”* This is still, however, a story about a black girl who is a maid, because colonialism, old or new, formal or implicit, is not only seizing land, but seizing a consciousness.

Kept Dependent

“The film is set during the first years of Senegal’s independence, while the short story takes place during the last years of the French presence in Africa…” writes Françoise Pfaff. “The fact that the social comments made in the book can be maintained essentially unchanged in the film indicates that for Sembéne, Senegal’s present political and economic systems are identical to those of a colonized country…In both contexts, Senegal is kept dependent.”**

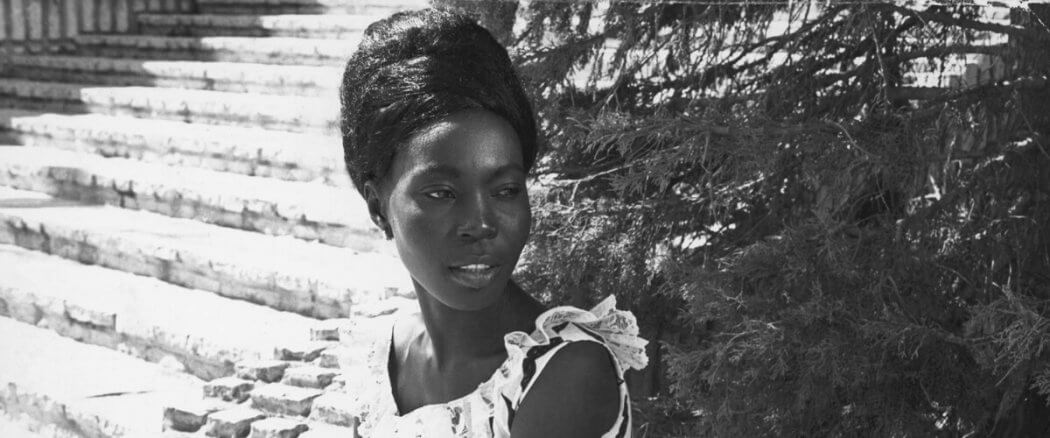

“It all began that morning in Dakar,” Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop) narrates*** in a flashback about 15 minutes into the film. After offering her services as maid throughout several apartment buildings and at various houses, a man passing by, who will eventually become her boyfriend (Momar Nar Sene) escorts Diouana to the “Maid’s Square,” where, along with others, she waits for the white women seeking help. One of them, known as Madame (Anne-Marie Jelinek), approaches the group, pacing before them, gazing from behind sunglasses. Madame selects Diouana, and, following an interview that consists of two questions — whether she can take care of children and if she has worked for white people before — hires her.

“It all began that morning in Dakar,” Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop) narrates*** in a flashback about 15 minutes into the film. After offering her services as maid throughout several apartment buildings and at various houses, a man passing by, who will eventually become her boyfriend (Momar Nar Sene) escorts Diouana to the “Maid’s Square,” where, along with others, she waits for the white women seeking help. One of them, known as Madame (Anne-Marie Jelinek), approaches the group, pacing before them, gazing from behind sunglasses. Madame selects Diouana, and, following an interview that consists of two questions — whether she can take care of children and if she has worked for white people before — hires her.

On a tide of jubilation, Diouana spills the news all over her village, even borrowing a tribal mask from her little brother as a present to the white couple. The work is predictable: playing with the children, walking them to and from school — and not without benefits: Madame bestows her old dresses, slips and shoes upon Diouana. When Madame suggests they all go to France, everything around Diouana becomes ugly, compared with the mirage of a “country whose beauty, richness, and joy of living everyone praise[s].”**** Soon, the couple, the children and Diouana have departed, leaving the other servants, and Dakar, behind.

Social Environment

While there is a clear chronology to the events, they are disclosed incrementally, through flashbacks and narration. Black Girl remains in the present: a relentless repetition of tiny rooms, increasing and tedious responsibilities, that Diouana is expected to proceed through with cheerful gratitude. “Madame wanted a servant who’d do everything,” Diouana realizes. “That’s why she chose me.”

![]()

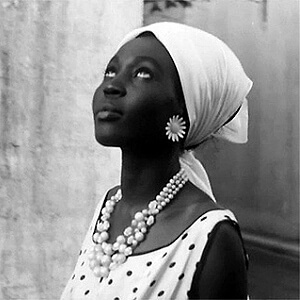

Diop is effective throughout the film, her debut as an actor, not overplaying a single note, as Sembéne anticipated: “Professional actors are simply not convincing as laborers, as ordinary human beings…[Professional actors in Senegal] who worked with us often had to be retrained…the school trained them in all the classic plays of seventeenth-century French theater…one has to erase all their training and return them to their social environment…[whereas] non-professional actors [are] somewhat the role they play, the way they believe, and everything else.”***** Diop is a designer and seamstress, vocations she continued every night when filming was finished. All of Diouana’s costumes are Diop’s creations, and her ability to communicate with and through them is a significant reason why her performance, and the film, are concurrently symbolic and fleshed.******

Diop is effective throughout the film, her debut as an actor, not overplaying a single note, as Sembéne anticipated: “Professional actors are simply not convincing as laborers, as ordinary human beings…[Professional actors in Senegal] who worked with us often had to be retrained…the school trained them in all the classic plays of seventeenth-century French theater…one has to erase all their training and return them to their social environment…[whereas] non-professional actors [are] somewhat the role they play, the way they believe, and everything else.”***** Diop is a designer and seamstress, vocations she continued every night when filming was finished. All of Diouana’s costumes are Diop’s creations, and her ability to communicate with and through them is a significant reason why her performance, and the film, are concurrently symbolic and fleshed.******

“The story of Black Girl is still relevant,” claims Diop, in an interview. “These things still happen, but they’re covered up. The other person is a human being just like you.” The film is a process of dehumanization, at turns subtle and blatant. “I’ve never kissed a black woman,” a man at a party remarks, pecking Diouana on each cheek. Humiliated, she retreats to the kitchen and sits at the table, while another guest pronounces, “with independence, the natives have lost a natural quality,” as though freedom were a matter of style. “He was just kidding around,” Madame explains to Diouana, sensing that confronting his behavior would necessitate confronting her own.

Saving Strength

“[Sembéne believed] that until Africa was able to make women equal to men…[it] would remain backward,” comments Diawara. “He didn’t believe in black superiority or white superiority…he believed in enlightened people. How do you enlighten people? Well, you have to do away with patriarchy…he said, ‘all the revolutions succeed when women participate in them.’”

It is not without intention, or irony, then, that Diouana’s boyfriend berates her playful attitude around a monument to freedom and indirectly leads her to the functional enslavement by the white couple. He, Madame and Monsieur fail to recognize Diouana’s saving strength — how her existence can give perspective and meaning to theirs — as all of us do when encountering the other.

“Cinema is like an ongoing political rally with the audience,” Sembéne analogizes. “In a movie theater you have Catholics, Muslims, Gaullists, Communists, if the film is good. Each sees what they want.” But Sembéne was an activist; in Black Girl, we see what he wants, and it sees us.

__________________________________________

Thanks to the Criterion Collection for their fantastic treatment of Black Girl. Quotes from Ousmane Sembéne, Manthia Diawara and Mbissine Thérèse Diop, unless otherwise noted, are from the supplements section.

*“[Sembéne] worked as a fisherman and an auto mechanic, among other jobs, before being drafted by the French Army in World War II. His experiences as a dockworker in Marseilles formed the basis of one of his novels.” “Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007)” by A.O. Scott. Black Scholar, Summer 2007.

**The Cinema of Ousmane Sembene, a Pioneer of African Film by Françoise Pfaff. Greenwood Press, 1984.

***The narration and dialogue for Diouana were supplied by a different actor, Toto Bissainthe, who matches and heightens Diop’s performance. The voices for Madame and Monsieur were also provided by other actors.

****From Ousmane’s novella.

*****Cinema, Pfaff.

******Also, “nobody has ever looked more chic.” Nick Davis. Film Comment, March/April 2017.