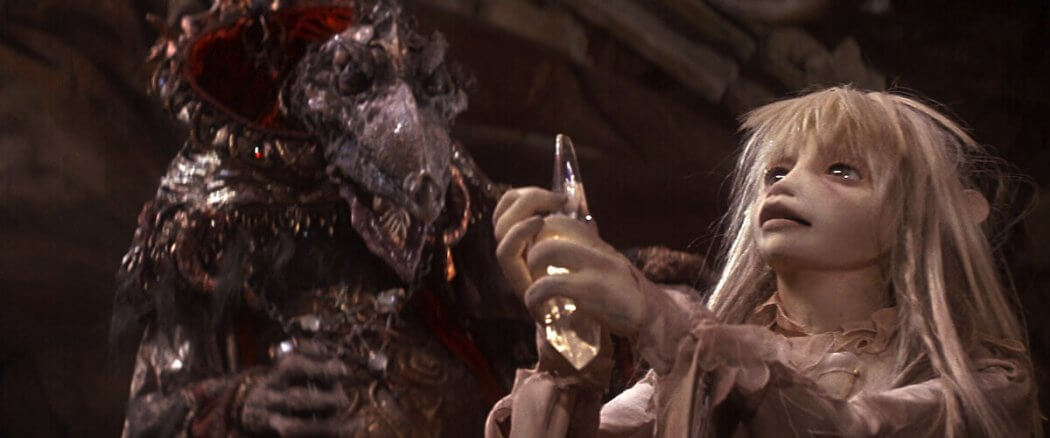

Until the last decade or so, good genre films were hard to come by. In the days of video rental stores, the fantasy and science fiction aisles were full of low-budget fare. For every classic like The Dark Crystal or The Empire Strikes Back, there were a dozen B-movies like Krull, The Barbarians, Deathstalker, and Space Raiders. Some of these were little more than a fantastically illustrated VHS cover coupled with oily, nearly-nude “actors” flailing around with swords and wrestling monsters. Thanks mostly to the success of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies, that has changed dramatically.

Regardless, genre films will always have challenges. Where fantasy literature has always been popular (Beowulf anyone?), fantasy has often been rejected by certain crowds. Christians afraid of exposing their kids to “The Dark Arts” (many of my Christian friends were in this category); Cultural elitists embracing realism and rejecting fancy as a distraction; Grown-ups who find it hard to suspend disbelief when the rubber monster suits are poorly made and the set pieces are clearly paper-mache rocks.

Regardless, genre films will always have challenges. Where fantasy literature has always been popular (Beowulf anyone?), fantasy has often been rejected by certain crowds. Christians afraid of exposing their kids to “The Dark Arts” (many of my Christian friends were in this category); Cultural elitists embracing realism and rejecting fancy as a distraction; Grown-ups who find it hard to suspend disbelief when the rubber monster suits are poorly made and the set pieces are clearly paper-mache rocks.

So why are we drawn to fantasy? Maybe it’s because all fantasy contain bits of allegory. Maybe it’s the magical powers and heroic action. In his essay “On Fairy-Stories” (PDF), Tolkien builds a case for why fantasy is crucial for our existence and lays out three values that are unique to the genre: Recovery, Escape and Consolation.

Recovery

Recovery gives us a sense of perspective, to recognize the uniqueness of the world we inhabit. Tolkien speaks of a kind of clarity, of seeing things as they were meant to be, which results from exposure to fantasy. In a nod to the smothering power of materialism, the fantastic reminds us that we cannot acquire or categorize the world. It is Other, outside of our grasp no matter how hard we try to possess it. Recovery shakes us out of our apathy so that all of our assumptions are turned on their head: the things we thought we knew are in fact not so easily known. Certainty is exchanged for surprise and the hidden power of mundane things is rediscovered.

Escape

Tolkien contrasts the “escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter.” Escape is a kind of resistance, for how can we scorn someone for trying to get out of a bad situation and go home? Or, barring that, dreaming of other things until escape becomes a reality? We are all, to some degree, held captive by pain, sorrow, injustice – and certainly all by death. Escape into fantasy offers a satisfaction of these “ancient desires.” In this way escape creates in us the “fugitive spirit” that resists as it imagines a better possible world.

Consolation

Finally, fantasy gives us consolation. That is: the “sudden joyous turn” we sometimes call the “happy ending.” In a beautiful linguistic flourish, Tolkien coins the word “eucatastrophe”. It is gospel, it is liberation in spite of sorrow and failure, it is a “fleeting glimpse of Joy beyond the walls of the world.” If Recovery makes us aware again of the potential for deliverance, and Escape allows us to hope in the midst of terror, Consolation is the fulfillment of the prophetic imagination triggered by Recovery. Eucatastrophe is a singular and miraculous grace that sets things to right.

Finally, fantasy gives us consolation. That is: the “sudden joyous turn” we sometimes call the “happy ending.” In a beautiful linguistic flourish, Tolkien coins the word “eucatastrophe”. It is gospel, it is liberation in spite of sorrow and failure, it is a “fleeting glimpse of Joy beyond the walls of the world.” If Recovery makes us aware again of the potential for deliverance, and Escape allows us to hope in the midst of terror, Consolation is the fulfillment of the prophetic imagination triggered by Recovery. Eucatastrophe is a singular and miraculous grace that sets things to right.

Exploring Secondary Worlds

Fantasy, sci-fi and horror genres may not be everyone’s preference, but careful digging can reveal a depth of meaning worthy of our engagement. Through a series of posts, I will be asking if Recovery, Escape and Consolation are still part of the fantasy stories we tell and if so, what are they saying? In the history of humans telling tales, we have always sought to build credible Secondary Worlds — worlds of our own design with rules and history and a “realness” that satisfies our senses. Tolkien argues that we build because we are made in the image of a Builder, and we create fantastic worlds because we long for “white shores, and beyond, a far green country under a swift sunrise” that is yet to be revealed.