It would appear that, over time, David Fincher’s Oscar-darling The Social Network has lost its luster. It was considered a Best Picture contender going into the show and ended up with a respectable, if somewhat underwhelming, 3 statuettes. And while The King’s Speech ended up taking home the award, movies like Inception, Black Swan and even Toy Story 3 are more likely to come up in casual film conversation.

And that’s not a total surprise. While Fincher’s Silicon Valley drama was critically acclaimed, it took some heat for being overly dramatized. Jesse Eisenberg was considered a revelation as Mark Zuckerberg, if only because the real person wasn’t quite as snooty or methodical. And nowadays, Facebook doesn’t look anything like it did back in 2010. After 7 years, the invention of several other social networks and multiple election cycles, Facebook has become less of the cool place to hang out online; now it’s more of a minefield for us to dodge amateur political humor and worn-out meme culture. Simply put: Facebook isn’t the same as it was then, and the film itself wasn’t the truest portrayal of how the website got its start. What’s the point of revisiting it?

The answer, it turns out, is one acquired by the passage of time. Upon re-examination, The Social Network is not designed to be a true picture of everyone’s hate-to-love website. It’s also not a reflection on the things that connect us to each other. On the contrary, it’s a fable on jealousy, loneliness and insecurity in an age where capital is king — and that capital is mythology.

A Nice Chair and a Better Idea

At one point during the film, Zuckerberg — the aforementioned Jesse Eisenberg, giving a career standout performance — says, “A guy who builds a nice chair doesn’t owe money to everyone who’s ever built a chair.” He’s referencing an ongoing lawsuit from the Winklevoss twins — Armie Hammer in his breakout role — who accused him of stealing their idea for the Harvard Connection. And in a sense, he’s right. Their idea for the Harvard Connection may be operationally similar to The Facebook, but it’s objectively a smaller, less successful ambition.

At one point during the film, Zuckerberg — the aforementioned Jesse Eisenberg, giving a career standout performance — says, “A guy who builds a nice chair doesn’t owe money to everyone who’s ever built a chair.” He’s referencing an ongoing lawsuit from the Winklevoss twins — Armie Hammer in his breakout role — who accused him of stealing their idea for the Harvard Connection. And in a sense, he’s right. Their idea for the Harvard Connection may be operationally similar to The Facebook, but it’s objectively a smaller, less successful ambition.

However, Mark’s chair comment isn’t born simply from having a better idea. As is common knowledge, he was forced to settle with the Winklevosses, albeit for pennies compared to what he is worth today. The money doesn’t lie — Mark did steal, at least in part, an idea. But I’d argue his idea for Facebook was borne more in jealousy. Not of the Winklevoss brothers though; of his friend Eduardo Saverin.

Saverin — credited as the co-founder of Facebook and portrayed by a high-strung Andrew Garfield — is Mark’s best friend at Harvard and one of the first believers in his idea. He’s also more popular and more successful than Mark. In the first moments of the film, Zuckerberg is meticulously calculating what it would take for a Finals Club to notice him. While he never finds the answer, Saverin is chosen out of nowhere. Throughout the process, we get a few very direct moments of Mark’s jealousy coming through. “It’s probably a diversity thing,” he says referencing Eduardo’s Jewish heritage. “Don’t be upset if you don’t go any further,” he suggests when Saverin makes the second cut for the club. And even though Saverin ends up giving up almost everything for Mark’s dream, that jealousy bubbles under the surface until an emotionally explosive climax in the new Facebook offices.

That the scene could be strongly considered the movie’s climax is indicative of where the film’s conflict rests. It’s not in the lawsuit Zuckerberg v. Winklevoss or even Zuckerberg v. Saverin. It’s between two friends, one who is “chosen” and the other who is not. Eduardo doesn’t owe Mark anything for his Finals Club experience, but he does end up paying.

Facebook Me

A major sub-thread of The Social Network’s Facebook story is the cool factor. It’s referenced only a few times in name, but many times in subtext. Eduardo wants to monetize the site early; Mark wants to keep it clean. Eduardo wants advertisers; Mark wants mythos. Mark’s move is smart in a business sense, but it ends up bringing him more trouble than it’s worth… figuratively.

A major sub-thread of The Social Network’s Facebook story is the cool factor. It’s referenced only a few times in name, but many times in subtext. Eduardo wants to monetize the site early; Mark wants to keep it clean. Eduardo wants advertisers; Mark wants mythos. Mark’s move is smart in a business sense, but it ends up bringing him more trouble than it’s worth… figuratively.

Sean Parker, the entrepreneur and Napster founder enters the scene in the midst of these discussions. His cool factor and legendary name allow Mark access to the biggest names in tech, securing Facebook’s road to mythical status. Parker, at least in the movie, is a major reason Facebook succeeds. But he also plays a major role in making Mark who he is.

(On a side note, I should say that Justin Timberlake might be the best part of the film from an acting standpoint. It’s hard to be a recognizable, multi-platform artist like he is and then absolutely disappear into a supporting role quite as well as he does. I think The Social Network was a Best Picture-worthy offering, but Timberlake’s lack of an Oscar that year is highway robbery.)

You see, Mark talks a lot about connection in The Social Network. It makes sense as Facebook is a venture built on the social desire to connect. Why wait to see that person you met at a party when you can instantly find them and talk online? And why be left out of the conversation on Facebook when you can have your friends send you an invite to sign up and become part of the group?

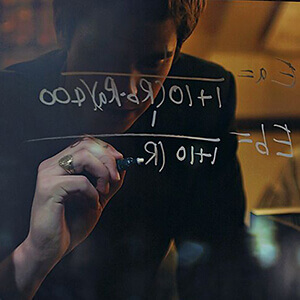

It’s interesting to see the way Mark is framed throughout the film. When he’s at Harvard, he’s mainly in small rooms with relatively small groups of people. When he’s not, he’s usually walking alone through a sparse campus. However, as Facebook picks up traction, we see Mark surrounding himself with more people. He lives in a California home with several other guys. He’s going to clubs and parties, or hosting large coding competitions with hundreds of people watching. All these moments are interspersed with looks at several depositions: Mark on one side flanked by his lawyers, endlessly defending himself with metaphors and Sorkin-sharp one-liners. In reality, the more time passes, the more lonely Mark appears. It all culminates with one final scene in an empty board room as Mark repeatedly refreshes his Facebook page, waiting for a response from…

Erica Albright

It feels wrong to leave out mention of Rooney Mara’s role in The Social Network. The fact is, it may be small, but it’s pivotal to understanding how Fincher and Sorkin want to portray their Zuckerberg.

It feels wrong to leave out mention of Rooney Mara’s role in The Social Network. The fact is, it may be small, but it’s pivotal to understanding how Fincher and Sorkin want to portray their Zuckerberg.

Mara’s Erica is only in a handful of scenes, and only one of them is substantial: the very first scene of the movie when she dumps Mark. The scene is textbook Sorkin as two very smart people exchange whip-fast dialogue deftly shifting in and out of context and subtext in a way that doesn’t feel clunky. No scene in the movie is as well-paced, and I would also argue no scene shows Mark at his most vulnerable. While he spends most of the movie talking about success, connection and money, we only ever see him for who he is — a 20-year-old kid who wants to be part of a Finals Club — in the bar with Erica.

Well, actually we do. And surprise! Both other scenes come with Erica as well. After The Facebook’s launch, Zuckerberg runs into Erica at a bar, hoping to talk with her. She politely declines, too hurt by his online taunts to entertain any sort of relationship. And at the end, we see her Facebook, a passive acknowledgement of her ex-boyfriend, as Mark awaits her literal acceptance of a friendship.

Jealousy may be the conflict driver and loneliness may be the consequences of Mark’s actions. But it is here — in the insecurity Mark feels in the wake of his break-up with Erica — where I think the movie’s heart rests. I’d be reaching to say The Facebook was at least narratively created all because of a break-up, but it feels short-sighted to not acknowledge how devastating the effects are to Mark. With Erica, he is his most honest and upfront while still maintaining his direct, overly-blunt nature. He even shows some humility. With everyone else, he’s the embodiment of Rashida Jones’ comments at the end of the film: “You’re not an asshole, Mark. You’re just trying so hard to be.”

Where we find our security is really the central question of The Social Network, and with the framework of the world’s most infamous social network, it’s one we’re forced to confront on multiple levels. Are we secure in our connections with the people around us? Do we invest all our emotional chips in success, money, or mythos? Or is there something else missing, something more worthy of our time, our heart and our work? We here at Cinema Faith would advocate for Jesus and the gospel, the only places where our worth is found not in ourselves, but in a more lasting, dependable source.

Regardless of where each person ends up, The Social Network provides a good base from which to start asking that question. And as the film ends, the last lines of text on the screen read, “Mark Zuckerberg is the world’s youngest billionaire.”

The look on Jesse Eisenberg’s face suggests it might not be worth it.