In my mind, one of the calling cards of all great movies is the way they stay with an audience well after the credits have rolled. Stunning visuals, great dialogue, actors at the height of their powers — these things are all fine. But there’s an indefinable quality that the best filmmakers seem to be able to hold onto that makes great films stick. Oftentimes, it’s the way a film builds around a memorable performance or to a climactic scene. Sometimes it can be something more subtle, like a score or even great cinematography. And other times, it’s something altogether different — an unsaid feeling that seems to grab on, refusing to let go even while the viewer lies in bed at night.

Steven Soderbergh is one filmmaker who understands this quality. It’s not present in all his films; making a great film is obviously easier said than done. But especially in the past decade — both before and after his “retirement” — Soderbergh has been inching toward this sort of fully realized vision. And after last year’s excellent Logan Lucky teetered just on the edge of greatness, Soderbergh has hit his tonal mark. His new psychological thriller, Unsane, is a masterpiece of sensory commitment. The entire film is committed to its unsettling premise, and it’s one of the most effectively chilling movies I’ve seen in the past few years.

But one important thing should be noted: Unsane is far from a great movie. In fact, at its core, it may be something altogether worse. For while Soderbergh’s craft is stunning, something sinister lurks deeper within.

Paranoia and Suspicion

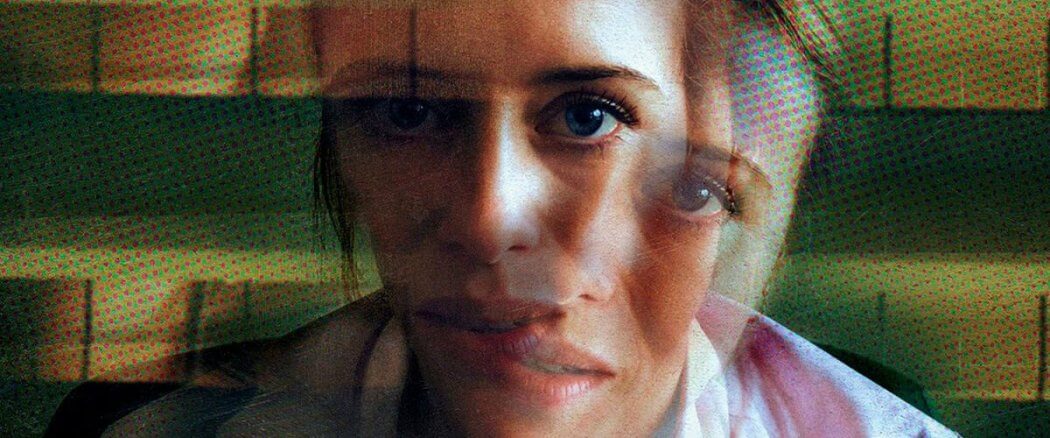

Early on, Unsane starts to feel a little bit off. Shot entirely on iPhones, we’re given an uncomfortably close view of Sawyer Valentini’s (Claire Foy, fresh off Netflix’s The Queen) seemingly solitary life. Her job is bland, her friends seem similarly so, and we really get a sense of cold distance in her demeanor. You’d be hard-pressed to call it suspicion if you didn’t know any better. Rather, she just feels… off.

This feeling is confirmed when Sawyer is involuntarily committed to a behavioral health center. Her proclamations to the appointed psychiatrist — she’s had detailed thoughts about how she would kill herself — seem troublesome enough to earn at least one night’s stay in the center. That’s where things take a turn for the worse as we start to question Sawyer’s credibility, her paranoia reaching a new level with each passing hour.

This feeling is confirmed when Sawyer is involuntarily committed to a behavioral health center. Her proclamations to the appointed psychiatrist — she’s had detailed thoughts about how she would kill herself — seem troublesome enough to earn at least one night’s stay in the center. That’s where things take a turn for the worse as we start to question Sawyer’s credibility, her paranoia reaching a new level with each passing hour.

It takes a while to get going, but the first 30-40 minutes really cement the feeling Soderbergh wants us to have. We go to the movies to suspend disbelief, and here the director is asking us to go one step further by uprooting our sense of reality every 5 minutes or so. It’s a unique strategy that runs the risk of going overboard, but Soderbergh shows just enough restraint by not going over the edge. Instead, he moves things along just at the right time by giving us a bit of a lifeline to hold onto. To talk any further about the plot would be entering spoiler territory, but it’s enough to say this feeling of suspicion we’re inundated with in the first third of the film carries into the film’s second and third acts. The whole thing is carried out masterfully by Soderbergh as he slowly dissolves our sense of truth, leaving us vulnerable to the twists and turns the script has in store.

Up Close and Personal

Soderbergh’s mastery carries beyond the sense of paranoia he builds visually.

An understated part of his work is the performances he gets out of his actors. Foy acquits herself well in almost every way, aside from some questionable accent work. It’s hard to connect with Sawyer by design, but Foy’s coldness is slowly revealed as something more empathetic — and frightening — as we learn more about her past. Part of this is the writing, but it’s also the way Foy plays her role with a complex feeling of resignation. Joshua Leonard gives a sterling performance as… well, maybe I shouldn’t say. And even Jay Pharoah (of Saturday Night Live impression fame) gives a worthy turn. It’s hard to see him outside of his comedic roots, but his role is understated enough to where his charm is still infectious while his limitations aren’t distracting.

One of the true stars of the film, though, is Soderbergh’s gritty camera work. There’s something deeply unsettling about the way Soderbergh both sees Sawyer and portrays her. The shots are neither tight or wide, settling in an uncomfortable medium range that feels intrusive. Think of someone invading your personal space, but not so much to where you would need to say something outright. This is the dominant way we see most of Unsane, but there’s enough traditional framing to heighten the feeling of discomfort.

The writing also plays a major role in the film’s sense of disquiet, quite an achievement for a writing team (Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer) responsible for both The Spy Next Door and Larry the Cable Guy: Health Inspector. If there’s any complaint, it’s that Foy’s dialogue can be uneven. But it plays well into the way her character is framed as unstable at first.

The writing also plays a major role in the film’s sense of disquiet, quite an achievement for a writing team (Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer) responsible for both The Spy Next Door and Larry the Cable Guy: Health Inspector. If there’s any complaint, it’s that Foy’s dialogue can be uneven. But it plays well into the way her character is framed as unstable at first.

There’s also a surprising amount of insight to be had within this script. Bernstein and Greer have a lot to say about role of mental health in the United States’ healthcare system, a theme Soderbergh touched on in Side Effects. However, there’s more to be said about the singular issue of abuse and how women are often the ones left traumatized and powerless. The way Sawyer’s life is uprooted and damaged by men is profoundly upsetting and wicked, and everyone involved seems interested in making us feel the ways her life has been changed. And it works.

Unfortunately, this is where the film also falls short, revealing its true intentions that could be characterized as “flawed,” or something entirely more sinister.

Crossing the Line

During the last 15 minutes of Unsane, I began thinking something I’d never thought about a film before: “There’s something evil about this.”

It’s hard to specify without giving away too many plot points, but I’ll try. By the final 15 minutes of the film, Soderbergh, Bernstein, and Greer have really put Sawyer through the ringer, and that’s probably being too callous about it. In truth, they’ve traumatized her character to a likely breaking point. And yet, Sawyer is also built to fight, and for every horrid thing she is put through, she is able to parry well, finding the strength from somewhere within to continue.

But once those final 15 minutes kick in, Unsane takes a disturbing turn from committed insight to voyeurism. Where the film once found Sawyer’s struggle as something to be marveled at, it suddenly finds a cruel pleasure in watching her suffer. When afforded an opportunity to restore her power, Unsane continues to bludgeon her. And ultimately, the hero is broken down. Does it show the commitment to the vision the film displayed for the first 80 minutes? Yes. But is it still admirable? That’s another question entirely.

There’s a discussion I often have with others about the role of darkness in art. It’s a topic most often broached with fellow Christians, but I also think it’s one everyone considers from time to time. When there’s an overwhelming presence of cruelty and evil in the art we consume, what role does redemption play?

I’ve often been of the mind that we’re not to shy away from the darkness of the world in the art we consume. Yes, there is much to be celebrated in our world, and we should dedicate as much (and arguably more) energy to affirming these qualities. But to ignore the other side of human nature is to make ourselves incapable of fighting against it. Sun Tzu’s command of, “know your enemy,” is an oversimplified way of saying this, but there’s some wisdom there. Maybe Peter’s command of, “Be sober and vigilant,” is more fitting. But I really found the crux of this film’s insidiousness in its lack of nobility. “Whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right… think about these things,” Paul writes to the Philippians.

I’ve often been of the mind that we’re not to shy away from the darkness of the world in the art we consume. Yes, there is much to be celebrated in our world, and we should dedicate as much (and arguably more) energy to affirming these qualities. But to ignore the other side of human nature is to make ourselves incapable of fighting against it. Sun Tzu’s command of, “know your enemy,” is an oversimplified way of saying this, but there’s some wisdom there. Maybe Peter’s command of, “Be sober and vigilant,” is more fitting. But I really found the crux of this film’s insidiousness in its lack of nobility. “Whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right… think about these things,” Paul writes to the Philippians.

Perhaps there is something commendable about Soderbergh’s realization of what he’s trying to say in Unsane. The entire film is effectively structured around the singular premise of making the audience uncomfortable… but to what end? Is it to tell us something sobering about the ways toxic systems disproportionately affect women? Or is it to find some sort of twisted cinematic thrill in watching Claire Foy’s character be utterly broken?

It’s pretty easy to see which movie Unsane wants to be. But the fact that it can’t see when it crosses the line makes it far from admirable. It might even make it damnable.