Whiteness in America, Michael Eric Dyson writes, is the result of “breaking down or, at least to a degree, breaking up ethnicity, and then building up an identity that was cut off from the old tongue and connected to the new land.” Whiteness takes many forms; it informs, establishing a social stronghold, and when that hold is resisted, it flees, like a demon, finding another form to possess. Whether I’m speaking metaphorically or literally is uncertain, as the evil is real and it influences our actions. “Slick and endlessly inventive, [whiteness] is most effective when it makes itself invisible, when it appears neutral, human, American.”*

Although not a single white person appears in Green Pastures — although it is “a very rare attempt to present a point of view that was Afrocentric”** — it is nevertheless inhabited by whiteness, which does not want to share as much as it wants to profit. Marc Connelly’s script, adapted from his play, is suggested by the writings of Roark Bradford, who lived on a plantation that functionally enslaved African-Americans, apparently interacting and even attending church with them. Power disparity would seem to undermine the authenticity of those relationships, and to be paid for writing about it is akin to lip-synching someone else’s recording at a concert; to quote Roxane Gay, “everyone has a voice.”

But I’m writing in the present, at the past, and even if it could write back, I wouldn’t be able to decipher it. Maybe I’m sabotaging the entire notion of addressing race in older films, but it cannot be ignored, or even separated, though I risk attempting the latter here. As Clover Hope writes, “it’s through this retelling of a gross past that the significance of our current discussions of race in Hollywood are given sterling clarity and context.”*** In one sense, Green Pastures is “a historical document,”**** but it’s also, in film scholar Ed Guerrero’s estimation, a flash of “the magnificent black talent that existed…as flawed as we might see it [with hindsight], we would [otherwise] never get to see performances by some of our greatest actors.” This review is for them.

Down on the Farm

“The whole story [of Green Pastures] is kind of contained in the Old Testament…” comments Guerrero. In viewing the adaptation of a holy text, as with any literary work, it is important to remember every reader will have a different conception of faithfulness to the source. Herb Boyd, activist and author, recalls watching the film with his wife, who was upset by some of the film’s Biblical inaccuracies, to which he laughed, “You can’t be that literal.”

To provide a detailed summary here would be, perhaps, succumbing to literalism, so in short, De Lawd (Rex Ingram) oversees Old Testament humanity — through a sampling of its Sunday school horror stories — and struggles to forgive and engage. We meet Adam, Eve, Cain, Abel, Noah, Moses and others, transposed into the city and the country of the 1930s, “at a time when there were two great migrations going on of black people into cities,” Guerrero says. “I think there were a lot of interests that wanted to keep black people down on the farm…that’s part of the ideological impulse behind [Green Pastures].”

To provide a detailed summary here would be, perhaps, succumbing to literalism, so in short, De Lawd (Rex Ingram) oversees Old Testament humanity — through a sampling of its Sunday school horror stories — and struggles to forgive and engage. We meet Adam, Eve, Cain, Abel, Noah, Moses and others, transposed into the city and the country of the 1930s, “at a time when there were two great migrations going on of black people into cities,” Guerrero says. “I think there were a lot of interests that wanted to keep black people down on the farm…that’s part of the ideological impulse behind [Green Pastures].”

Conflicted Context

“Black actors…right up ‘til blaxploitation — weren’t sure how many film roles they would actually get,” Guerrero recounts. “So every time they came on screen was a once-in-a-lifetime performance…you got brilliant performances in maybe a conflicted context.” Even as a white person, I was conflicted by the conditions of the characters — there are black maids in heaven, the pain of which is not lessened by the fact that all of heaven is black***** — there is a pattern and style of speaking, which is universally applied in the film but was only true in part of the black population — and so on. However, yes, the performances are brilliant, so it’s time I talk about those.

Rex Ingram, as De Lawd, is a perfectly imperfect reflection of God’s light. Ingram’s compassion is all-encompassing; he is one of few actors I’ve seen who do not cry, they weep, and it is almost overwhelming. Burton compares him to Morgan Freeman at one point in the commentary, but I suspect that’s because it was recorded only a few years after Bruce Almighty. To me, Ingram has a posture and command, but also a humility and kindness, with no comparison or equal. And he moves from glory to glory, portraying De Lawd and Adam, throughout the film, sometimes interacting with himself! There is speculation about this casting choice, including suggestions of budget and scheduling, but it seems obviously a Theological statement: we are made in the image of God. Although, ironically, Ingram is so good that I didn’t know he was playing both roles until I looked at the cast list.

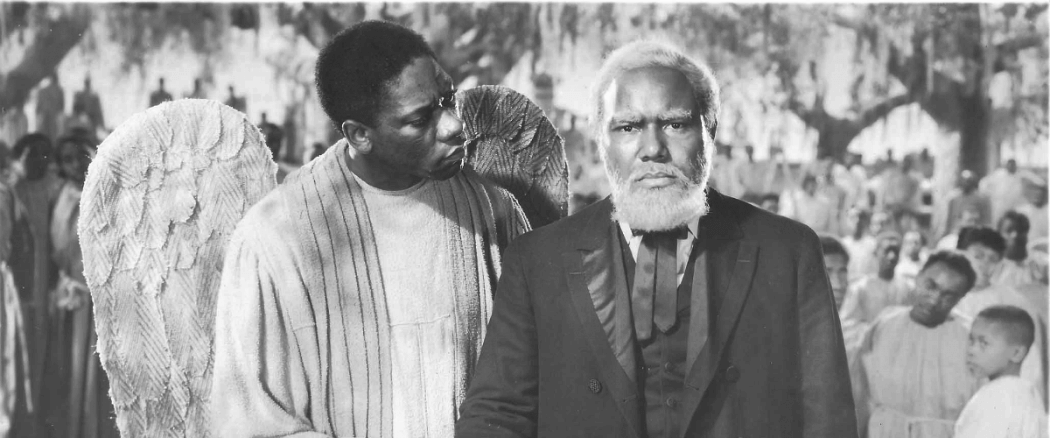

Oscar Polk, as Gabriel, is quite a refreshing contrast to typical interpretations of the angel and a tuned counterpart to Ingram’s Lawd, delivering lines with a gentle lilt that conceals and carries a range of emotions, holy and un. Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson, as Noah, pointedly downplays every line and reaction, claiming some of the funniest — and most reverent — parts of the film. And even though the only ways of being black and female at the time were, in Guerroro’s words, “sexless mammy” or “loose woman,” the actors persist; in particular, Edna Mae Harris, as Zeba, playing the ukulele, singing, smiling and switching sides at every back that turns, somehow remaining both believable and likable.

Oscar Polk, as Gabriel, is quite a refreshing contrast to typical interpretations of the angel and a tuned counterpart to Ingram’s Lawd, delivering lines with a gentle lilt that conceals and carries a range of emotions, holy and un. Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson, as Noah, pointedly downplays every line and reaction, claiming some of the funniest — and most reverent — parts of the film. And even though the only ways of being black and female at the time were, in Guerroro’s words, “sexless mammy” or “loose woman,” the actors persist; in particular, Edna Mae Harris, as Zeba, playing the ukulele, singing, smiling and switching sides at every back that turns, somehow remaining both believable and likable.

The Other Side

“It is scarcely possible to think of a black American actor who has not been misused: not one has ever been seriously challenged to deliver the best that is in him…” writes James Baldwin in his collection of film criticism, The Devil Finds Work. “What the black actor has managed to give are moments — indelible moments, created, miraculously, beyond the confines of the script: hints of reality, smuggled like contraband into a maudlin tale, and with enough force, if unleashed, to shatter the tale to fragments.” Every actor in The Green Pastures offers these moments, with dignity, grace, and even delight.

How? Maybe, as Burton remarks, “there’s been an historical link…in the African-American community…to the Old Testament, because it is about deliverance, and it is about the struggle of man, and it is about that ultimate reward…for having endured suffering in this lifetime, there is, you know, in heaven, for you…all that you have been deprived of in this life. I think there is a natural link for a people who come from an enslaved consciousness to want to know that there is something better on the other side.”

81 years later after this film was released, I imagine there are very few black people who would declare they are on the other side. But it is stunning how lament can still blossom into celebration. So I honor these actors for struggling, for striving to be free, surrounded by the fences of whiteness, in pastures that were only green for those who took the land. I have hope they are living elsewhere now, in a house owned by their Father, to whom they bear such a resemblance.

__________________________________________

*Both quotes in this paragraph are from Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America by Eric Michael Dyson, St. Martin’s Press, 2017.

**LeVar Burton, in a superb DVD commentary, from which I also quote Ed Guerrero and Herb Boyd throughout this review.

***Clover Hope, “How I Am Not Your Negro Is a Reminder of Hollywood’s Power to Lie,” Jezebel, February 3rd, 2017.

****Burton.

***** Hattie McDaniel: “I’d rather play a maid and make $700 a week than be a maid and make $7.”