The legacy of Johnny Cash is eternally tied to the concept of, “walking the line.” The 1956 ballad is one of his most enduring hits. The 2005 Hollywood biopic took its name from the same song. His public struggles with substance abuse (and later declaration of Christian faith) all played into the weaving meta-narrative of Cash’s career. If life was a series of lines, Cash stumbled in and out of all of them, somehow finding one greater, uniting line on which he was able to balance.

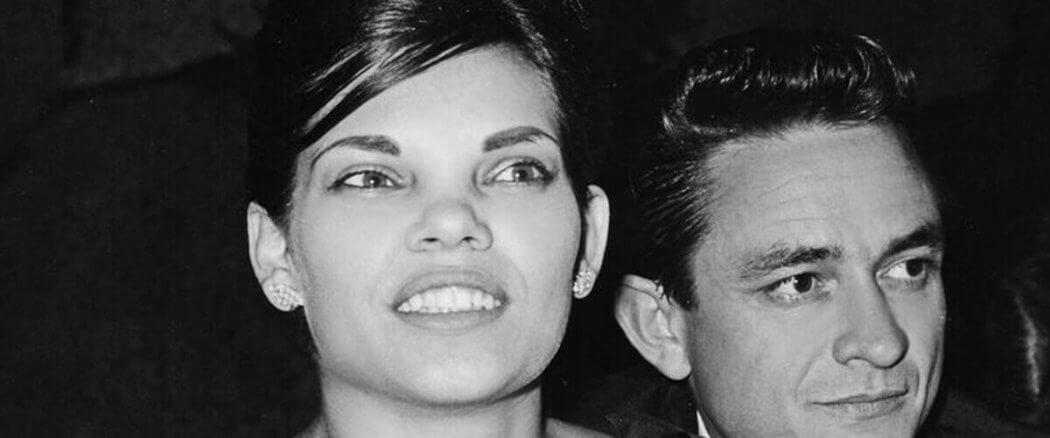

Matt Riddlehoover’s My Darling Vivian, however, isn’t interested in the Man in Black. Rather, it zeroes its focus in on the woman for whom, “I Walk the Line,” was originally written – Cash’s first wife, Vivian Liberto. Told through the stories of their four daughters (Roseanne, Kathy, Cindy and Tara), Vivian is a by-the-numbers interview doc – you won’t get any fresh perspectives on Cash or his second wife June Carter. It’s a family affair, through-and-through, giving Vivian’s story an emotional weight that compensates for the lack of “access.”

Matt Riddlehoover’s My Darling Vivian, however, isn’t interested in the Man in Black. Rather, it zeroes its focus in on the woman for whom, “I Walk the Line,” was originally written – Cash’s first wife, Vivian Liberto. Told through the stories of their four daughters (Roseanne, Kathy, Cindy and Tara), Vivian is a by-the-numbers interview doc – you won’t get any fresh perspectives on Cash or his second wife June Carter. It’s a family affair, through-and-through, giving Vivian’s story an emotional weight that compensates for the lack of “access.”

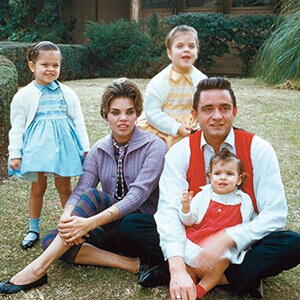

It’s also these ties that bind that help the film avoid maudlin sentiment. The Cash daughters refrain from painting their mother as the victim of Cash’s infidelity and substance abuse, but rather his absence. It’s about as matter-of-fact as a story can be – “Dad was famous, so he had to be gone a lot.” Their delivery isn’t as begrudging as it is melancholy, and Riddlehoover lets their memories build the mythology of Vivian’s heroic, imperfect motherhood. Stories often begin with, “I don’t know if this was true,” or, “mom always said.” Vivan’s ability to juggle four children under 6, along with the perils of matrimony with a “tortured” artist, give her the stature of a Greek goddess – powerful, capable and prone to human error.

That’s not to say there isn’t a villain in this story. The film certainly isn’t kind to the memory of June Carter Cash, painting her as the beneficiary of Vivian’s strife. The film draws a stark and purposeful line between itself and the 2005 film Walk the Line, which often paints Carter as the hero of Cash’s story. Riddlehoover’s connections (his husband is Kathy Cash’s son), encroach most directly here, allowing for a more traditional antagonist to enter the picture at the expense of the film’s tone. Does it make the film a little easier to digest? Perhaps, but it also sacrifices some of the inherent goodness in Vivian’s story.

But Carter ultimately isn’t painted as the main obstacle in Vivian’s story – rather it’s the shadow created by her ex-husband’s enduring celebrity. Liberto – who later remarries to become Vivian Distin – is effectively written out of Cash’s legacy. She’s the footnote to Cash’s Hollywood romance with Carter, the spot on his resume that reveals some of the ugly underbelly of his spot in 20th century American history. My Darling Vivian isn’t as interested in unpacking the overtly racist and sexist narratives that propelled Cash and effectively quashed Vivian’s place in his story, treating them as a drive-by example of her struggle to endure. It’s unfortunate, as the choice to dig deeper would have created something more complex and urgent than the film ends up becoming. Vivian’s story is worth the telling, but Riddlehoover can sometimes lose the plot on why.

That doesn’t mean, though, that the film isn’t effective at drawing viewers in. Cash’s daughters, together, create a story-telling dynamo that paints Vivian in a three-dimensional light. The film augments these stories with fresh visuals, including never-before-seen photos and video from the Cash family’s life in the 50s and 60s. These are effectively brought to life by the power of Riddlehoover’s editing, which may be the most valuable part of the film. He makes the strange choice to add flourishes of special effects (smoking cigarettes, overused film projection filters) that distract from the power of the raw footage, almost as if he doesn’t understand that the material is noteworthy on its own. Vivian’s story has constantly lived under the shadow of another – why not bring it to life and let it be?

Despite it’s faults, however, My Darling Vivian is a worthwhile meditation on female legacy and agency, and how easily it can be co-opted by a man. Told through the eyes of her daughters, the film gives Distin’s story the attention it deserves, allowing her a life beyond Cash’s influence. It can be a troubled exercise, but as My Darling Vivian shows, no amount of hardship was able to keep Vivian and her story from pressing onward.

Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the SXSW Film Festival in Austin, Texas, was forced to cancel its annual gathering. Just over a month after the initial dates were scheduled, SXSW launched a 10-day virtual fest with Amazon Prime, highlighting several documentaries, features and shorts that would have shown in Austin.