Mully is a documentary that tells the story of the extraordinary life of Charles Mully. Mully’s story is so impossible that if you pitched it to a studio, they’d tell you to try telling a true story with some elements of reality in it.

Come to think of it, if you pitched Mully’s story to your mom, she’d tell you to try telling a true story with some elements of reality in it. Mully’s tale has the air of Cruise on the Burj Khalifa to it. Awesome. Breathtaking. Impossible (I know, I said that already).

So, let me quickly dispatch with a concise film review: an extremely well-edited film that marries original-source and found footage with dynamic interviews of all the principals. It looks great. It’s well-shot, and the filmmakers used a variety of cameras to get the job done, including a DJI GoPro. The music is solid.

Something that I wasn’t a huge fan of, but am not sure what I’d do to replace, is the opening re-creation scenes. Obviously no one had footage of young Mully at his hut in Kenya, but recreations in documentaries grey the border between a narrative film and a documentary.

Well-constructed and moving, the film demonstrates its legitimate pedigree (executive produced by an Oscar-winning producer, James Moll) and deserves every award it has won (which includes the Audience Award at the Austin Film Festival).

(That’s right, the AUSTIN FILM FESTIVAL, so when you or your friends start running your mouth bemoaning that Christian filmmakers are terrible and don’t get it and can’t connect, please remember the whole “Mully won the Audience Award at the Austin Film Festival” thing.)

But the reason it won the audience award is the story. Mully’s story will make you recalibrate your life. You must see Mully because you forgot what we are capable of.

No Mere Mortals

In “The Weight of Glory (PDF),” C.S. Lewis (if you had the “under” on over/under 500 words before Greg quotes C.S. Lewis, congratulations!) reminds us that “there are no mere mortals”:

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization — these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit — immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.”

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization — these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit — immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.”

And before your local demon gets to work explaining that Lewis was an old British guy who doesn’t understand the world today, or the way things really go, go see Mully.

I’m not sure if it’s worth it for me to try and recount every incredible detail of his life, but Mully was abandoned at age six by his family, begged until he was in his late teens, then worked as a servant in a wealthy home in Nairobi. From there he became a business owner, and then an incredibly wealthy husband and father of seven, and then the owner of the gas and oil monopoly for his country.

But that’s not the story at all. He left that all behind.

Father to the Fatherless

Charles Mully abruptly decided one day to change everything in his life. And when he did, he changed the lives of thousands and thousands of people. From all I observed, Mully’s power isn’t in a special set of talents, but in a specific way of believing — tenaciously, completely, until everything around him is changed.

Mully asked God to show him what to do, and then became convinced God told him to care for the thousands and thousands of orphans in Nairobi. One by one, five by five, he would pick them up and take them back to his mansion. His biological children were disgusted and angry. His wife humbly tried to object. He kept bringing kids home.

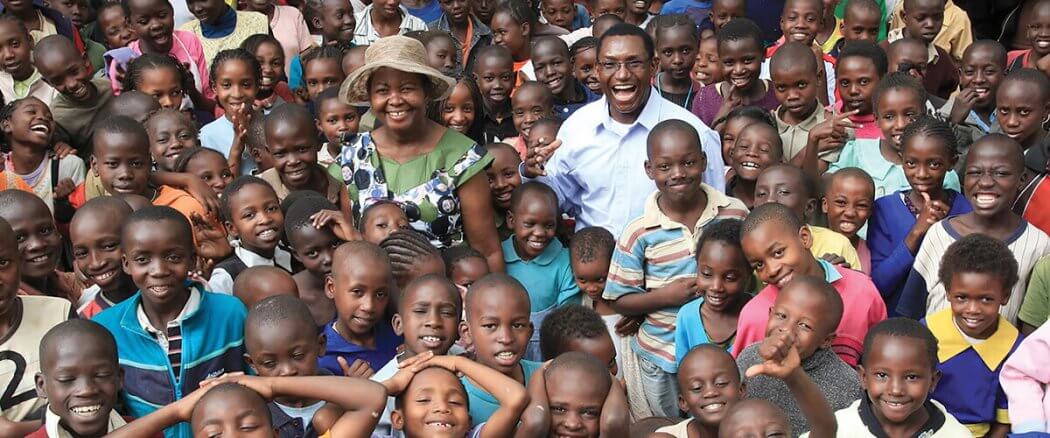

More kids, and more kids came home, until they couldn’t fit in the mansion or the extra dormitories built on his compound. He fed them, clothed them, educated them. They helped out and called him “daddy.”

We watch children explain that they were forced into prostitution, until Mully pulled them out. Children lost, abandoned, hopeless.

We watch children explain that they were forced into prostitution, until Mully pulled them out. Children lost, abandoned, hopeless.

There’s an incredible sequence where he and his family build a large bridge over a parched part of their new compound. He explains that someday they will walk over the water under that bridge.

So — later in the film, after the incredible water divining scene and the whole part about how they are slowly changing Kenya’s climate, we cut to a scene of Mully watching over the bridge over a lush green area and water.

So, truly, as a filmmaker, all you had to do was turn the camera on. But director Scott Haze and editor Alex McKenzie did far more — evoking a real sense of tension and storytelling that captured this remarkable man and the faith that guided his story.

Today, Mully Children’s Family has campuses all around Africa and the world. He has helped to foster and support twelve thousand kids. The film moves us with interviews of adults he brought home who now hold doctorates and are pursuing advanced degrees (which Mully is paying for). Children tossed away and abandoned who discovered their worth when Mully took them home. Perhaps we’ve been so intent on posting on Facebook that we forgot we can change the world. Mully didn’t.