Early in Klute, Bree Daniels (Jane Fonda) returns home from an afternoon appointment with a John, has a bath, lights some candles, pours a glass of wine and sits at her kitchen table, smoking a joint with a clip. After a few drags she begins singing in a husky alto:

We gather together

to ask the Lord’s blessing

He hastens and chastens

His wisdom divine

and from the beginning

the fight we were winning

“I don’t know why I did that — it just came out,” Fonda admits, “and the director, Alan Pakula, always one to appreciate contradictions, left it in.” But Fonda’s love for Protestant hymns* provides the why, and in 1971, there were plenty of fights, most of which she joined: the Vietnam anti-war efforts, the second wave feminist movement, the struggle for Native American rights, not to mention the sexual revolution, which “was in full battle.”** This battleground is where Klute settles, a shifting terrain of “power [and] sex, and the impotent and the powerful, and sex being used as power.”***

Honest, Decent Men

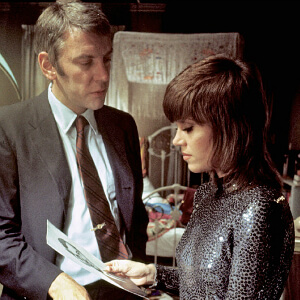

“There are thousands of honest, decent men who simply disappear every year,” an FBI Investigator declares generally, though he specifically means Tom Gruneman (Robert Mill), who has been missing for six months. Tom’s wife (Betty Murray) and coworker (Charles Cioffi) are frustrated with the FBI’s lack of progress, so they hire John Klute (Donald Sutherland), because “[he] knew Tom…he’s interested, and he cares.”

Of course, this is a Pakula film, so the disappearance is only the front of a massive weather pattern that’s moving in, always overhead. At the eye of the storm is Bree Daniels, an actor who is trying to leave prostitution, even as a former John is following her around, calling at random times, breathing. Klute begins the search for Tom with Bree, but his investigation will ripple outward and inward, upsetting truths for which no one is prepared.

Point of View

“The movie should probably be titled Bree instead of Klute, because the Fonda character is at the center…the film examines their somewhat strange relationship, and at the same time functions on another level as a somewhat awkward thriller…” writes Roger Ebert. “Shots of hands gripping a mesh fence shots [are] not very satisfactory because the wrong point of view is established. One thing about a thriller is that the threat should always be seen from the point of view of the threatened.”

Perhaps that is a valid critique, but it seems more an unintended study in irony: Ebert appears unaware of male privilege even as Klute is hyperactively so. The film’s “wrong point of view” critiques the omnipressiveness of patriarchy by visually defining it through the male gaze, in which “[Bree] is a tiny figure…always being squeezed or isolated.”**** Meanwhile the script and Fonda’s performance gaze back, through an authentic female character grappling with the limited role assigned to her by the consequences of sin, where she desires a man only to find herself under a ruler. These toggling and conflicting points of view give the film tension and truth. “Without [being] heavy-handed,” Molly Haskell writes, “it dramatize[s] the exploitation of women.”

Perhaps that is a valid critique, but it seems more an unintended study in irony: Ebert appears unaware of male privilege even as Klute is hyperactively so. The film’s “wrong point of view” critiques the omnipressiveness of patriarchy by visually defining it through the male gaze, in which “[Bree] is a tiny figure…always being squeezed or isolated.”**** Meanwhile the script and Fonda’s performance gaze back, through an authentic female character grappling with the limited role assigned to her by the consequences of sin, where she desires a man only to find herself under a ruler. These toggling and conflicting points of view give the film tension and truth. “Without [being] heavy-handed,” Molly Haskell writes, “it dramatize[s] the exploitation of women.”

The Woman’s Film

“The rhythms of melodrama and the rhythms of character study are totally different,” Pakula said. “A melodrama has a kind of inevitable, relentless rhythm. A character study has a much more leisurely rhythm…what I wanted to do was to make [them] come together, and make them be one and the same.”

It’s a brilliant idea, and like most brilliant ideas, not original. Klute is rather a ‘70s version of Now, Voyager, with its interests in psychoanalysis, the need to feel beautiful, the need to be loved, and, naturally, the quest to transform oneself. Most of those concerns are common in “The Woman’s Film,” a genre with numerous triumphs, spanning from the ‘30s to the ‘50s. Some feminists are still derisive of this kind of filmmaking, and at the time of Klute’s production, there was a strident consensus on the subject. Haskell was an exception, arguing in her definitive work From Reverence to Rape that many of the leads in “The Woman’s Film,” amidst others from the era, simply reflected “a deep polarity within women themselves.”*****

Klute revisits this tension, and in 1971, there weren’t many films doing it. “Directors wanted Hollywood money to make non-Hollywood films, and were able to do so for a brief period,” said Haskell in a recent interview. “But since they weren’t tied to one studio, they didn’t have to satisfy the idea of making sure you have a woman in a major role in your film, or making male movies that also had some appeal for a female audience…The whole development of movies as properties was built on the idea that you had to keep both men and women in mind. And now suddenly, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, here came these directors who didn’t know how to use women, and didn’t have to anyway.” Pakula didn’t start directing until the late ‘60s but had been working in film since the late ‘50s. He knew how.

Klute revisits this tension, and in 1971, there weren’t many films doing it. “Directors wanted Hollywood money to make non-Hollywood films, and were able to do so for a brief period,” said Haskell in a recent interview. “But since they weren’t tied to one studio, they didn’t have to satisfy the idea of making sure you have a woman in a major role in your film, or making male movies that also had some appeal for a female audience…The whole development of movies as properties was built on the idea that you had to keep both men and women in mind. And now suddenly, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, here came these directors who didn’t know how to use women, and didn’t have to anyway.” Pakula didn’t start directing until the late ‘60s but had been working in film since the late ‘50s. He knew how.

Collision of Opposites

“[Pakula] had a profound interest in and empathy for women’s emotional and psychological processes…” Fonda relays. “He had a fascination, as I do, for why people do the things they do.” This inquisitiveness wasn’t just mining for new material — though the artist is never quite free from that impulse — it was Pakula’s desire for understanding. It was a desire that made him a great collaborator. “He loved…that he and 125 of his close friends were going to show up every morning and figure out all the problems,” Celia Costa, Pakula’s location manager for eight films, said. “He was very receptive to the…ideas of the people who worked on the film.”******

Klute buzzes with everyone’s best ideas, most of which come from Pakula’s frequent collaborators. Fonda, who would star in two more films under his direction, gives a performance that’s electrifying in its spontaneity and control; as Pauline Kael observes, “she has a special kind of smartness that takes the form of speed; she’s always a little ahead of everybody.” Michael Small, composer for nine of Pakula’s films, wrote a score with “exotic percussion — African, Chinese, you name it,” and the eerie sound of a woman singing that Pakula titled “‘the siren call’ — [not] only the signature of the killer, it’s also the very seductive force that Bree is putting out.”

And then there’s the inimitable cinematography of Gordon Willis, determining “[the] film’s visual structure as a collision of opposites.”******* At one point, calling to make an appointment with a John from a telephone booth in the middle of the afternoon, Bree is in total shadow. As she hangs up the phone, church bells begin ringing in the distance, and she crosses some invisible line where the sun reaches, illuminating her. It’s among many moments — of dark and light, man and woman, sin and self-control, victim and perpetrator, power and weakness — in a film about the battle of duality.

__________________________________________

*”I loved Protestant hymns — loved singing them and loved hearing them. Today I often find myself singing those hymns when I’m fly-fishing or pulling weeds.” Jane Fonda: My Life So Far by Jane Fonda, Random House, 2005.

**”Queen of Tarts: What is one of the Quickest Ways to Get Oscar Attention? Lie Down on the Job.” Lisa Schwarzbaum, Entertainment Weekly, 2/28/1996.

*** Alan J. Pakula: His Films and His Life by Jared Brown, Back Stage Books, 2005.

****Pakula, Brown.

*****From Reverence to Rape by Molly Haskell, New English Library, 1974.

******Both quotes in this paragraph are from Pakula, Brown.

*******“Remembering Gordon Willis, the Cinema’s Prince of Darkness” by Richard Corliss, Time.com, May 23, 2014.