A helicopter roars past. A napalm bomb explodes. A song about “the end” plays. And a man’s face slowly comes into focus, upside down, contemplating it all. The perfect opening to a perfect film. Welcome to Apocalypse Now. Prepare to be blown away.

Benjamin Willard is a soldier. There’s no such thing as R&R for a man like Willard. He spends his rest dreaming of the jungle. He relaxes by waiting for a mission, and a mission is exactly what he gets. Summoned to a meeting of high ranking officials, Willard gets handed a dossier. Inside, is a picture of Colonel Walter E. Kurtz. Who is Kurtz? What has he done? Why does the army want him dead? The rest of the film uncovers the answers.

But Apocalypse Now is about much more than a mission and a man. The quest for Kurtz is really a catalyst for an outsider’s glimpse of war. By standing outside the Vietnam conflict, the viewer remains detached from either side, and can judge both impartially. Where most war movies clash good vs. evil, Apocalypse Now tells the truth. Both sides are fighting for their country. Both sides are right, and both sides are wrong. There’s nothing black and white about war.

A Classic

The most striking thing about Apocalypse Now is how timeless it is. Here’s a movie that could open in theaters this Friday and feel just as modern and relevant as anything else playing. Francis Ford Coppola directs with laser precision, using POV shots and intricate lighting to create an overwhelming sense of dread. Not a second is wasted. Every scene enthralls. Not bad for a three hour film from 1979.

The acting is outstanding. Martin Sheen plays the main character, Willard. You’d be forgiven for thinking of his son, Charlie. The resemblance is uncanny. But nothing Charlie Sheen has done can compete with this. Martin Sheen’s Willard is a time bomb waiting to explode. On the surface, he’s the perfect solider. On the inside, he’s falling apart at the seams. Then, there’s the supporting cast — Robert Duvall, Laurence Fishburne, Dennis Hopper, and Marlon Brando. Everybody brings their A-game to this one, as if they knew they were creating something special.

So many scenes stand out. One of the most unforgettable comes early on when we’re introduced to Robert Duvall’s Colonel Kilgore. Willard asks Kilgore to fly in his boat so he can start his journey up river to Kurtz. They talk about a few possible entry points. One looks promising, but it’s filled with Viet Cong. At first, Kilgore seems concerned. Then, someone mentions how big the waves get there. Kilgore’s eyes light up. No Viet Cong army is going to get in the way of a great surfing peak.

So many scenes stand out. One of the most unforgettable comes early on when we’re introduced to Robert Duvall’s Colonel Kilgore. Willard asks Kilgore to fly in his boat so he can start his journey up river to Kurtz. They talk about a few possible entry points. One looks promising, but it’s filled with Viet Cong. At first, Kilgore seems concerned. Then, someone mentions how big the waves get there. Kilgore’s eyes light up. No Viet Cong army is going to get in the way of a great surfing peak.

The next day, Kilgore and his men fly in on helicopters. They put “Ride of the Valkyries” on loud speakers to announce their approach. Just as the anticipation reaches its peak, Coppola cuts to a village with women going about their day and school children lining up for class. Suddenly, in the distance, we hear the music. They’re coming. The children start to run. Kilgore’s team opens fire. Vietnamese soldiers run to their posts to defend the village. We see handmade bridges blown up, grass huts torn in two, and lives ended on both sides. All so Kilgore and his men could go surfing.

This scene, like the rest of Apocalypse Now, works on a number of levels. It’s exciting, tragic, comic, and powerful all at the same time. Duvall gives his iconic line about loving the smell of napalm in the morning, but his last words are the most profound. He shoots Willard a wistful look and says, “You know, some day this war’s gonna end.” The thought makes him sad.

The Problem of War

A central question runs through the whole of the film: is Kurtz insane? The army thinks so. The generals play ominous recordings of Kurtz for Willard to paint a picture of a man driven over the edge. But then we meet Kurtz, and our opinion changes instantly. Nothing he says sounds insane. In fact, quite the opposite. Marlon Brando works his magic here. He gives Kurtz presence. When this man speaks, you stop and listen.

The key to Kurtz comes in a monologue he gives about a time where he and his soldiers inoculated a village. They gave children the polio vaccine, only to discover later that the tribal leaders had cut off every inoculated arm and placed them in a pile at the center of the encampment. Kurtz was horrified at first. Then, it dawned on him — that’s how you win a battle. Kurtz says, “If I had ten soldiers like that, our troubles here would be over very quickly.” This speech reveals the problem of war.

The key to Kurtz comes in a monologue he gives about a time where he and his soldiers inoculated a village. They gave children the polio vaccine, only to discover later that the tribal leaders had cut off every inoculated arm and placed them in a pile at the center of the encampment. Kurtz was horrified at first. Then, it dawned on him — that’s how you win a battle. Kurtz says, “If I had ten soldiers like that, our troubles here would be over very quickly.” This speech reveals the problem of war.

Boot camp is about turning men into machines. There’s no room for second guessing on the battle field. A soldier responds to every command with two words — “Yes, sir.” They’re taught to kill without mercy. They’re taught to hate the enemy. An entire people group is reduced to the term “Charlie” because if the people you’re killing are real human beings with souls, you might flinch, and that means coming home in a body bag. Kill or be killed, soldier. That’s the rule of the jungle. It’s also the opposite of what God created us to be.

The Early Church

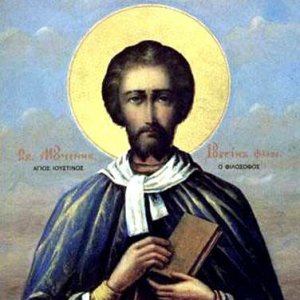

For the early church, being a soldier was unthinkable. The church fathers couldn’t imagine splitting allegiance between Jesus and the Roman army. How can you love your enemy and kill him at the same time?

Justin Martyr said “We, who in past times, killed one another, do not now fight with our enemies. We, who had been filled with mutual slaughter and every wickedness have each one — all the world over — changed the instruments of war, the swords into plows and the spears into farming instruments, and we cultivate piety, righteousness, love for men, faith, and the hope which is from the Father himself through the Crucified One.”

Justin Martyr said “We, who in past times, killed one another, do not now fight with our enemies. We, who had been filled with mutual slaughter and every wickedness have each one — all the world over — changed the instruments of war, the swords into plows and the spears into farming instruments, and we cultivate piety, righteousness, love for men, faith, and the hope which is from the Father himself through the Crucified One.”

Today, things are different. Ever since Constantine merged the Roman Empire with Christianity, we lost the early church’s wisdom. To even question a soldier’s vocation is offensive, especially among Christians. We’re Americans. We’re the good guys. Being a pacifist is unpatriotic. But as Christians, our allegiance isn’t bound to flags or borders. Our allegiance is to a different kingdom altogether.

Redemptive Violence

No matter how good a country’s intentions are for starting a war, everything gets muddled in the end. We joined the Vietnam War to stop the spread of communism. Our involvement lasted 10 years. 50,000 American lives were lost. The death toll of the Vietnamese was in the millions. During the war, American soldiers perpetrated one of the greatest atrocities in military history called the “My Lai Massacre” where between 300 and 500 unarmed civilians were tortured and killed. That wasn’t an anomaly. A sergeant later testified under oath to witnessing a “My Lai each month for over a year” between 1968 and 1969.

Maybe Kurtz saw similar atrocities as an officer. One of the recordings the generals play for Willard is of Kurtz talking about a snail crawling across the edge of a razor blade. The army listened to that tape, from the comfort of home base and roast beef, and called him insane. But Kurtz wasn’t insane. He saw things clearly for the first time in his life, and the truth broke his soul in two. He saw what was required to be an effective soldier. He saw the hypocrisy of his commanders. He saw the evils of war. Everything became clear, and he couldn’t take it anymore. When will we do the same?

Every few years, when an enemy like ISIS comes along, we take the myth of redemptive violence down from our dusty shelves. We blow the dirt off, and think maybe it’ll work this time. Maybe this time, it will lead to peace. That’s the greater tragedy. We don’t learn from our mistakes. Nations ignore the history books. Christians ignore their roots. Meanwhile, our bombs continue to destroy homes that people built brick by brick. Our guns continue to kill people that desperately need the love of Christ. Our soldiers continue to come home with broken hearts and shattered souls.

That’s the horror. The real horror.