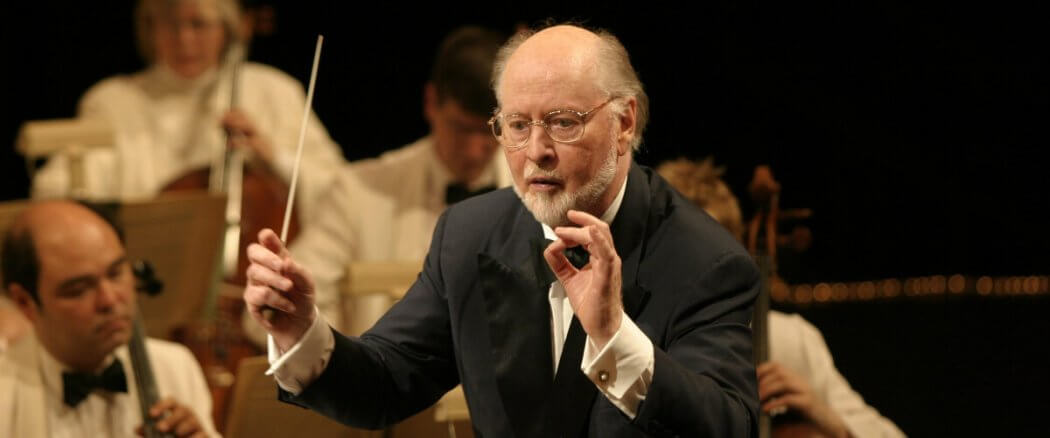

If one wishes to compose music for film, one cannot necessarily hope to get famous doing so. One cannot expect to have his or her music played regularly or have their name be recognizable to anyone outside of the world of film. Film music is designed to stay in the background. Unseen. Unconsciously heard. Safe in the shadows. Supporting a story that so many other artists are all trying to tell in unison under the guidance of the director. As a film composer, if your music draws a lot of attention to itself, you’re probably not doing your job effectively. However in this article, we shall once again shine the spotlight on a composer whose music both transcends the movies to which it belongs, while simultaneously embedding itself as an imperative element in the storytelling of those films. It’s that paradoxical success that has inadvertently made this gentleman a household name. That name is John Williams.

Jammin with John

The Maestro, as he would come to be known, grew up in a very musical home. His father being a prominent radio percussionist in his day. This childhood environment led Williams to stumble upon his gift. Regularly during Williams’ childhood, he would invite other musically inclined neighborhood friends of his to have a “little jam session,” in his words. Williams played the piano, and his brother the drums. One day, when playing with a friend of theirs who could play the trumpet, Williams realized that in order to play a song together, he needed to adjust the trumpet notes on the page a step so they could play together. Something clicked. As Williams expresses in an interview for Music Express Magazine, “The fun of that, and the sense of discovery that one could adjust, manipulate, arrange music and then have the joy of doing it with someone else was, I think, one of the most profound experiences I had as a young person.” This moment was one of the first to teach Williams the unitive power of music.

Williams would go on, in his young adulthood, to work as a pianist for contract orchestras in Los Angeles, the most fortuitous of which being Columbia Studios under Morris Stoloff. Much like Hans Zimmer making coffee for Stanley Myers, Williams took advantage of his front-row seat in the composer’s process, and eventually was asked to write a cue for a tired composer. Then another cue. And another. Until eventually, Williams established himself as a film and TV composer to be sought after.

Williams would go on, in his young adulthood, to work as a pianist for contract orchestras in Los Angeles, the most fortuitous of which being Columbia Studios under Morris Stoloff. Much like Hans Zimmer making coffee for Stanley Myers, Williams took advantage of his front-row seat in the composer’s process, and eventually was asked to write a cue for a tired composer. Then another cue. And another. Until eventually, Williams established himself as a film and TV composer to be sought after.

Them Themes

Williams’ sound is lushly orchestral, utilizing every instrument in intricate ways, bringing out the full vibrancy of the orchestral sound. In a medium that’s becoming increasingly digital, The Maestro has continued to stay relevant by not treating the entire orchestra as a single instrument, and using each sound to unique effects. He favors brass much of the time, especially as lead performers for his heroic themes. In some of his dramas, however, such as Schindler’s List, Seven Years in Tibet, and Memoirs of a Geisha, he turns to string soloists to draw out the fragile laments of the characters in those films. He has played around with some pretty unique solo instruments as well, such as the tuba that bellows out Jabba the Hutt’s theme in Return of the Jedi, and the harp/contrabassoon duet for the three-headed dog (“Fluffy”) in The Sorcerer’s Stone.

“Life is a great gift. Life itself is just that we’re here, and we think, and we can share things, and see what’s beautiful, hear what’s beautiful…Find the joy in music, find the joy in life, find the joy in each other, find the joy in work, and life becomes really very very beautiful that way, I think. Go out and find the joy.”

But of course, the main thing that makes Williams so popular is his knack for creating memorable and resonant themes. From the simplicity of the infamous two-note Jaws motif, to the rich melodies in Harry Potter, it seems any blockbuster Williams touches leaves audiences singing the tunes. During production of the 4th Indiana Jones film, a franchise Williams has scored since its genesis, director Steven Spielberg reflects, “Every morning, y’know, you come on the set and there’s an electrician whistling the Indiana Jones theme, or there’s somebody humming it, or — we couldn’t go anywhere where somebody didn’t start singing that song!”

Williams, in a 1997 interview for Total Film Magazine, describes his famous themes as being a necessary element in helping a film tell a story. “Something in the third act, which you can reach back and quote as an old friend from act one can be part of the structure of what makes the soundtrack of the film unified and solid and function well.” A grand majority of film scores all have reoccurring themes like Williams describes here, but unlike most, many of his themes have become recognizable to general moviegoers outside of the films themselves. That’s rare.

Gentle Genius

Despite being the most popular film composer in the mainstream world, I personally find him to be one of the most elusive personalities in the scoring world. He doesn’t give as many insights into his process as some composers are doing nowadays. In the interviews he does give, he speaks with eloquence and gentle sincerity, constantly expressing his great gratitude for the accolades he receives, but he doesn’t act as proud as one might forgive him for acting, given his accomplishments. He doesn’t act like he’s anything special, but that he somehow has been placed in a very special position in life where he gets to participate in the joy of his craft. J.J. Abrams, who worked with Williams on Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and is currently working with him on the 9th installment of the franchise, echoes this in a 2015 interview with Tavis Smiley, “He doesn’t speak like a man who has accomplished anything… it’s not false modesty, he is simply just this artist who just does this thing and claims almost no responsibility for it.”

When he speaks of his process of creating the iconic themes he’s so famous for, he emphasizes the difficulty of creating them. They didn’t just come to him magically. They are the result of hours upon hours of obsessive tinkering and revision. “I spend more time on those little bits of musical grammar, to get them just right so that they seem inevitable. They seem like they’ve always been there…and spend a lot of time on these little simplicities, which are often the hardest things to capture,” he expresses in a behind-the-scenes featurette for Indiana Jones. Despite the frustration he expresses he has with creating his tunes, you can still sense the same childhood joy he finds in discovering each well-placed note.

When he speaks of his process of creating the iconic themes he’s so famous for, he emphasizes the difficulty of creating them. They didn’t just come to him magically. They are the result of hours upon hours of obsessive tinkering and revision. “I spend more time on those little bits of musical grammar, to get them just right so that they seem inevitable. They seem like they’ve always been there…and spend a lot of time on these little simplicities, which are often the hardest things to capture,” he expresses in a behind-the-scenes featurette for Indiana Jones. Despite the frustration he expresses he has with creating his tunes, you can still sense the same childhood joy he finds in discovering each well-placed note.

Favorites

Here’s the geeky part again.

With the abundance of great iconic work under Williams’ belt, I’m gonna limit my favorites to only, well, my favorites, which aren’t necessarily the most famous of his work. If you’re not sure if you’ve heard any of John Williams’ music, look him up on IMDB. You’ll realize you have.

Hook (1991) — The most underrated score of Williams’ career, I would argue. I recently discovered that the film was originally intended to be a musical, and many of the themes in the actual score were written as melodies for the songs first. That makes too much sense, because the score is one of the most thematically dense that Williams has ever written. There’s a unique new sound for each segment. It’s an emotional journey. From fun and catchy, to operatic and mournful, from gritty and swashbuckling to tender and light. It’s unashamedly my favorite Williams album. It has all of his strengths stuffed into one score. (No favorites)

Harry Potter 1-3 (2001, 2002, & 2004) — The genius of these scores are hard to put into words. They’re so good that they made the subsequent efforts by other very talented composers seem lackluster by comparison. Williams’ Potter scores are filled with a childlike sense of wonder, playfulness, chaos, fear, and adventure. What’s more, he was able to expound on his already vibrant work in the third film, adding elements of old medieval music, a waltz, and a manic jazzy piece for the Night Bus sequence. (Favorites: “Harry’s Wondrous World,” “Fluffy’s Harp,” “Hedwig’s Theme,” “Fawkes the Phoenix,” “Hagrid the Professor,” “Mischief Managed!”)

Harry Potter 1-3 (2001, 2002, & 2004) — The genius of these scores are hard to put into words. They’re so good that they made the subsequent efforts by other very talented composers seem lackluster by comparison. Williams’ Potter scores are filled with a childlike sense of wonder, playfulness, chaos, fear, and adventure. What’s more, he was able to expound on his already vibrant work in the third film, adding elements of old medieval music, a waltz, and a manic jazzy piece for the Night Bus sequence. (Favorites: “Harry’s Wondrous World,” “Fluffy’s Harp,” “Hedwig’s Theme,” “Fawkes the Phoenix,” “Hagrid the Professor,” “Mischief Managed!”)

Seven Years in Tibet (1997) — Another highly underrated Williams work. It features one of the most hauntingly gorgeous themes I’ve ever heard from him, played with such elegance by cellist Yo Yo Ma. I don’t understand how the main theme is able to evoke feelings of mourning and euphoria at the same time. The rest of the score is bit different from the main theme, featuring a lot of atmospheric percussion and Tibetin chanting. The theme is so good that that’s all I wanted to listen to when I first heard it, but I learned to appreciate the atmospheric nature of the rest of the album over time. A genius work. (Favorites: “Seven Years in Tibet,” “Regaining a Son”)

Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) — A haunting masterpiece, featuring cello solos from Ma, and violin solos from Itzhak Perlman. How can you go wrong! The score walks you through the protagonist’s emotional journey vividly, as if you’re feeling everything she feels at each point in the story. Gorgeous work. (Favorites: “Going to School,” “The Chairman’s Waltz,” “Confluence”)

“Music is not verbal. We don’t know what it means. We don’t know what poetry means. If we read poetry as prose, we miss it. It lives somewhere else. And so, as music does, as poetry does, as myth does, it speaks to part of our humanity that we recognize as very much there within all of us.”

Jurassic Park (1993) — What more can be said about this score than it’s a brilliant work for the best dinosaur film ever made. The themes bring so much wonder and terror to the creatures and, as with many Williams score, gives the film an extra sense of magic it wouldn’t otherwise have. (Favorites: “Theme From Jurassic Park,” “Journey to the Island”)

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) — The Indiana Jones films hold a very special place in my heart and remind me of simpler times in my own teenhood. This score was the one I listened to the most in that time, and it still holds up. It perfectly captures the film’s sense of fun and adventure, all grounded in a father/son relationship at its core.

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) — The impact of all the Star Wars scores is undeniable, but this one in particular is my favorite. It introduced the iconic Imperial March, which is a brilliant work. I don’t understand how the musicians are able to play so consistently fast. It also perfectly captures the playful wisdom of Yoda and includes a riveting tune for the asteroid chase scene. (Favorites: “Yoda’s Theme,” “The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme),” “The Asteroid Theme”)

Coda

I love film music, in case you can’t tell. I’ve loved it since I was about 9 years old. And most of the people I talked to about it growing up didn’t care much. It’s just the “background music” from a movie. It isn’t always considered a legitimate art form, I find. However, the genius of Williams has helped bring recognition and legitimacy to the art of film scoring, for which I am grateful.

Next up, one of my personal favorites, Thomas Newman.

__________________________________________

John Williams Interview for Music Express Magazine: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNX2rNaCDso

1997 John Williams Interview for Total Film Magazine: https://www.douban.com/group/topic/1029416/

John Williams Scoring Session for Indiana Jones: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THMZl5OfCHQ

John Williams Interview on Star Wars VII Music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIfWfengo3E

John Williams Interview on Scoring Star Wars: The Phantom Menace: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQX70Va3tuA