“You’re no use to anyone now.” — M to James Bond in Die Another Day, 2002.

“I volunteered because of a lie.” — Jason Bourne

James Bond and Jason Bourne, the two super spies of cinema. They stand alone at the top of the genre as the two most recognizable and influential characters in the espionage business (with perhaps honorable mention being due to Austin Powers). To date, Bond and Bourne have produced 29 films, between them that have grossed a combined $8.6 billion. The Bond franchise, alone, spans over a half century of continual production, making it one of the longest continually-running film series of all time.

Such rich cinematic history gives us a unique opportunity to analyze not only their entertainment and artistic contributions but also the greater culture that produced them. It’s worth a short series of articles.

A Day of Terror

Let’s back-track fifteen years. When we pinned up our 2002 calendars, we were only a few months removed from the day the two towers crumbled and dissolved before our eyes. We’ve never been the same since, and as always, film changed with the times.

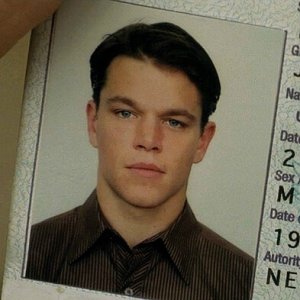

Fifteen years ago Pierce Brosnan had finished his Bond career with his fourth film, Die Another Day, but that same year also witnessed a new espionage film and a new hero, the debut of Matt Damon as Jason Bourne. Bourne would capture the public’s imagination and eclipse James Bond, at least temporarily, creating something of a crisis for the Bond franchise.

The success and superiority of Bourne wasn’t immediately obvious at the time. Who knew, back then, if the Bourne series would have the staying power, and if you looked at the numbers, Die Another Day made more money, way more money. It was big budget with all the Hollywood hype. Even so, for film enthusiasts and critics, it was obvious that Bourne was tapping into something significant, both cinematically and culturally, while Brosnan’s final Bond movie, on the other hand, was an absolute disaster.

The success and superiority of Bourne wasn’t immediately obvious at the time. Who knew, back then, if the Bourne series would have the staying power, and if you looked at the numbers, Die Another Day made more money, way more money. It was big budget with all the Hollywood hype. Even so, for film enthusiasts and critics, it was obvious that Bourne was tapping into something significant, both cinematically and culturally, while Brosnan’s final Bond movie, on the other hand, was an absolute disaster.

This was the immediate aftermath of 9/11, and we were subdued, uncertain, and insecure. This was back when I was in my early twenties, when I voted for George W. I remember kicking back with my roommate in the evening each week to tune in to the thinly veiled imperialist propaganda TV series 24. We would watch Jack Bauer gouge eyes and break necks, doing whatever it took (legal or not) as time ran out, as the clock ticked away the seconds in Jack’s attempt to foil the terrorist plots and save America, to save freedom and democracy, etc.

But whether you were on the right or the left, whether you supported an Iraq invasion or not, these were sober times. We felt edgy, all of us, and in this grim cultural milieu, the old Bond formula was a thing of the past. The breezy Bond, that old swash-buckler of a Bond that Sean Connery invented (and perfected), the archetypal Bond seemed immature after 9/11, even inappropriate.

Keep Your Tip Up: A Tale of Two Spies

In 2002, the Hollywood answer, the big business answer, was predictable: keep the same product but rebrand. Die Another Day was an attempt to give the old Bond a little bit of an edge, to create a slightly grittier, somewhat darker Bond while still retaining the signature Bond tom-foolery. Watching the film fifteen years later, it’s obvious that they were playing to a trend, treating the Copernican turn of 9/11 as though it were a fleeting fad — and it’s painful to watch.

The attempt to be edgy falls short in large part because Die Another Day still falls back on the wonky and ridiculous Bond formula, like when a snow machine materializes, inexplicably, simply appearing out of nowhere right when Bond needs it — oh, and conveniently for Bond, he’s got a parachute that he’s able to use to lasso the guy who’s driving it so that Brosnan can commandeer the vehicle.

There’s even juvenile sexual puns. I see you handle your weapon well, a beautiful woman says to Bond. I have been known to keep my tip up, he replies. It’s material better suited for Austin Powers, and I say this as a lifelong lover of puns.

More to the point, Brosnan’s Die Another Day Bond has no character that you can sink your teeth into. This Bond is confused. He’s dealing with something of an identity crisis, something that he can’t acknowledge, a crisis of identity that he isn’t self-aware enough to understand. He is both heavy and not, he is the light and breezy Bond and then he’s not, he’s trusting and then he’s not. He seems bitter and resentful from his months/years in a Korean torture hellhole — dark and gritty Bond — then he shaves and puts on his tux for martinis and fine dining.

There’s no core to this Bond, no compelling pathos, and at the same time, it’s clearly because the writers and film makers simply have no vision. Watching it today, it’s as though even the film makers themselves have realized that the Bond thing wasn’t going any further, that it had run its course, and that even the film makers have thrown the towel in on the Bond franchise.

There’s no core to this Bond, no compelling pathos, and at the same time, it’s clearly because the writers and film makers simply have no vision. Watching it today, it’s as though even the film makers themselves have realized that the Bond thing wasn’t going any further, that it had run its course, and that even the film makers have thrown the towel in on the Bond franchise.

It was never easy to pull of a good Bond film. Roger Moore understood from the beginning of his Bond days that the character of Bond was ridiculous. The irony is that his insight actually made Roger Moore a good Bond. Moore didn’t take his Bond role seriously, and as such, he succeeded. He understood that the Bond character that Connery created was a caricature, and it takes a special kind of talent and vision to pull it off with any amount of artistic integrity.

Bourne, by contrast, was a blank slate, a new start. In 2002, Bourne was a man on a mission, a desperate man, sober, serious, and substantial. There were no corny penis jokes, no glamorous women to ogle, no flashy cars to drive, and no martinis. There was only his single-minded quest for the truth and a scramble to survive.

We meet Bourne on a dirty fishing boat, a neurotic with a short fuse who doesn’t even know his own name. From that point, he’s always trying to stay one step ahead, but time and again he’s frustrated and finds that he’s actually one step behind.

He throws himself into finding out his true identity, with a stark sense of urgency and an earnestness that contrasts with the aimlessness of Brosnan’s Bond. Jason Bourne learns, he uncovers information, but this is a double-edged sword. Like the knowledge of good and evil, every revelation only reveals that he’s in deeper shit than he ever could have imagined.

Who am I?

Answer: you don’t want to know.

Bourne Identity and American Amnesia

Bourne’s journey mirrored my own, and many others. It mirrored our own spiritual and national amnesia. Like many of my peers, I was taught a sanitized, glorified version of American history, a Christian ideology of “one nation, under God.” Sure we had our messy periods — what with slavery and that nasty bit with killing all of those Indians — but we fixed all that, didn’t we? The America of today is a land of opportunity, opportunity for all, isn’t it?

When it became obvious that the Bush wars had failed, when it became clear that no one in the financial sector would be prosecuted for the crash, and when it hit me that there would be no major reforms to the financial sector after the global financial crisis of 2008, I started reading Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. I joined Occupy a few years later. I began to ask questions. Among many questions, there was one that seemed central: who are we, as a people?

Answer: you don’t want to know.

Fifteen years ago was the beginning of Bourne’s manic search for an identity, and it was the beginning of our own nation’s loss of innocence, in a way, at least for those of us in the white, male majority, those who historically were able to occupy an unquestioned position of privilege. It was the beginning of an unraveling that would work itself out over the next decade and a half, slowly but in earnest and with an ever building sense of urgency.

Who are we? Are we a benevolent empire, like that portrayed in the Bond films, a nation that is essentially good, a beacon for freedom and democracy, Reagan’s shining city on a hill? This is the patriotic ideology of the early 1960s that could overwhelmingly identify with Sean Connery and glorify his Bond character, the debonair secret agent, the handsome white male who glides through life with ease, women and enemies alike falling down before him.

Who are we? Are we a benevolent empire, like that portrayed in the Bond films, a nation that is essentially good, a beacon for freedom and democracy, Reagan’s shining city on a hill? This is the patriotic ideology of the early 1960s that could overwhelmingly identify with Sean Connery and glorify his Bond character, the debonair secret agent, the handsome white male who glides through life with ease, women and enemies alike falling down before him.

Within this ideology, all of our enemies are labeled simply as “evil.” In Bond’s world, it’s black and white, we don’t bother with nuance. We’re the good guys, and our purpose and end justify any means.

Or are we a society from the Bourne films, a people whose national crimes have been covered up, whose dirty deeds are done in secret and whose corruption is buried or hidden in classified documents, never to be spoken of, forgotten and gathering dust? In the Bourne world, one might see the terrorist attacks of September 11 or the Great Recession of 2008 as being examples of America’s chickens coming home to roost, to borrow Malcolm X’s provocative phrase.

Here in the U.S., the tension between these two identities has only been building, since 2002, and now we are a nation divided, in conflict and in crisis. Our elders say that they haven’t seen things so divided since the 60s.

Knowledge of Good and Evil

Comparing and contrasting Bond with Bourne is an intriguing exercise that affords a unique pay off. The sheer size and scope of the cinematic material lets us appreciate the way these two characters have been handled through the generations. To analyze these films is to pull back the veil on the dominant ideologies at work during this time of cultural conflict and tension, and the Bond and Bourne films seem uniquely positioned, enmeshed and intertwined as they are in our national narrative, embedded in our history.

To engage Bond and Bourne is to deconstruct our own national narratives, to question the stories we tell ourselves, questions about the American Dream narrative itself. Are these questions that might possibly provide a small measure of wisdom to navigate these increasingly uncertain times? Or is it a truth we’d rather not look at, like the knowledge of good and evil itself? To borrow my favorite line from the second Bourne film, “You’re in a big puddle of shit, Pamela, and you don’t have the shoes for it.”