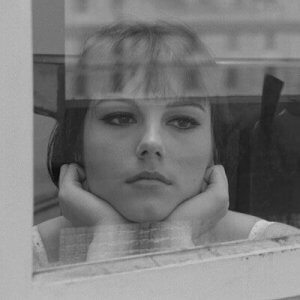

I Knew Her Well opens with a landscape shot of a beach, steadily panning across the sand and continuing onto the body of Adriana Astarelli (Stefania Sandrelli). We are primed to assume that, like many others before and after it, the film is objectifying women. But the shot is a masterful preview of a piece concerned with how people can be deformed into extensions of their oppressive environments; or, as Walter Wink describes them, “the invisible forces that determine human existence.” That existence, in director Antonio Pietrangeli’s view, has been dehumanized to such a degree that we struggle to relate.

The obsession of the film is a question posed, through various forms, by Pietrangeli: what does it mean to know someone?* To explore the possible answers to that, he chose a woman as guide, which, as Sandrelli notes, was “quite unusual at the time.” Unusual, yes, but also logical: in 1965 Italy, women were among the most marginalized by social systems. Also, Pietrangeli loved women. Especially Adriana.

Daily Humiliations

Adriana (Sandrelli) is a country girl from Tuscany who has moved to Rome to pursue acting in the cinema. Naturally, she works other jobs too: as an usherette at a theatre, where she watches the stars and lip-synchs their lines; as a stylist in a salon, where she sings along to the radio. Throughout the film’s “19 micro sequences,”** Adriana meets a string of “so-called wonderful guys” who are mostly charlatans, if they’re lying, and narcissists, if they’re honest. Some of them, usually through good fortune instead of actual skill, advance her career, a pursuit for which she suffers daily humiliations.

To provide more of a synopsis is unnecessary, as the plot is episodic, prone to flashbacks and exists only to enhance the main female character, and of how many films can you say that? “It’s really a collage of tender moments that reveal how open Adriana is to the world, to humanity, to people,” Sandrelli explains. “I have [that] in common with Adriana.” Sandrelli also emphasizes that trait in Pietrangeli. “His sensitivity was a sort of fragility, but it also allowed him to understand — he was a director who loved women…so this sensitivity, this complete openness — he’d get deep inside the character, inside the film, practically monitoring the heartbeat of the film, scene after scene.”

To provide more of a synopsis is unnecessary, as the plot is episodic, prone to flashbacks and exists only to enhance the main female character, and of how many films can you say that? “It’s really a collage of tender moments that reveal how open Adriana is to the world, to humanity, to people,” Sandrelli explains. “I have [that] in common with Adriana.” Sandrelli also emphasizes that trait in Pietrangeli. “His sensitivity was a sort of fragility, but it also allowed him to understand — he was a director who loved women…so this sensitivity, this complete openness — he’d get deep inside the character, inside the film, practically monitoring the heartbeat of the film, scene after scene.”

One of the strongest heartbeats is a scene about halfway through. It’s a rare, humane interaction for Adriana, and, appropriately, it’s with a boxer, who earns a living through abuse. “It takes a great passion to get pounded like that,” Adriana remarks without irony. “Don’t let them beat you to a pulp!”

Women, Body and Soul

“We approached the character with great affection,” remembers Sandrelli. That quality distinguishes I Knew Her Well from other comparable films of the era, such as Who Are You, Polly Magoo? and Darling. In particular, the value of Sandrelli’s performance cannot be overstated; its assurance gives the film a kind of equilibrium. But then this was a film made by a “director who loved women, body and soul,” recollects Sandrelli. “He was sort of…overawed by us women, us actresses.”

Indeed, that love was the body and soul of Pietrangeli’s work, including a film titled Hungry for Love, in which a brothel closes and a group of the displaced prostitutes open a restaurant, but are gradually, devastatingly, dragged back into the life they left. “Pietrangeli was really invested in a mission,” observes film scholar Luca Barattoni, “the mission was to take Italian culture out of the provincial.” Was this mission a type of liberation Theology, advocating for the emancipation of women? Yes and no, because the best of I Knew Her Well interrogates even that notion, wondering why women’s newfound “freedom” is still defined by their relations with men.

Indeed, that love was the body and soul of Pietrangeli’s work, including a film titled Hungry for Love, in which a brothel closes and a group of the displaced prostitutes open a restaurant, but are gradually, devastatingly, dragged back into the life they left. “Pietrangeli was really invested in a mission,” observes film scholar Luca Barattoni, “the mission was to take Italian culture out of the provincial.” Was this mission a type of liberation Theology, advocating for the emancipation of women? Yes and no, because the best of I Knew Her Well interrogates even that notion, wondering why women’s newfound “freedom” is still defined by their relations with men.

No Ideas But in Things

“No ideas but in things,” William Carlos Williams wrote. The finest artists follow this advice, and Pietrangeli and his team are among them, transmitting complex ideas with cunning subtlety and clarity. There is the recurring imagery of containment and mobility — or, concerning the latter, the lack thereof — functioning as shorthand for the modernity that imprisons us: horses in the back of a truck, friends crowded in a small car, and people trapped in an elevator, of which a character complains, “it has a mind of its own.” And there is the pop music, a constant companion and questionable influence on Adriana, featuring such soothingly patriarchal lyrics as “I’d known for centuries you were mine” and sentimentally unstable as “every love that dies is the end of a world.” The sound design, specifically, is as incidental as it is involved, adding character and meaning in powerfully motivated and unexpected ways.

And I Knew Her Well’s final moments are some of the most unexpected in cinematic history. I will not reveal them here. I will only quote Molly Haskell: “in every movie where a woman [excels] as a professional she [has] to be brought to heel at the end.” Maybe Pietrangeli was susceptible to the same chauvinistic tropes as many others, but I’m more inclined to accept the ending as Adriana’s response to the reality of being dominated by systems and the people who represent them; of feeling unknown by the One who knows and loves the deep waters of her heart and longs to fight the principalities and powers with her. As Abraham Heschel writes, “few are guilty but all are responsible.”

__________________________________________

Thanks to the Criterion Collection for their customarily excellent treatment of I Knew Her Well.

*Luca Barattoni, in the CC’s special feature on Antonio Pietrangeli.

**Barattoni.