Disney’s Queen of Katwe remains within the tradition of unintentional Christian filmmaking that prefers subtle nuances and unspoken demonstrations of conviction over tired clichés, recycled tropes, wooden characters, and soap-boxy platitudes positing overly simplistic answers to the complexities of life lived in a fallen world. In veteran director Mira Nair’s vision, we see strands of references to faith organically and quietly pervading the film without ever becoming overbearing or overt. Here, we have the kind of creative and engaging expression of spirituality found in such recent works as 2015’s Selma and The Revenant and this year’s Hail Ceasar!, Hell or High Water, and Birth of a Nation.

Based on true events as chronicled in the 2012 book Tim Crother published for ESPN, Katwe stars David Oyelowo as Robert Katende, a sports ministry leader who often opens chess matches with a word of prayer and employs culturally-significant parables as a means of motivating his players to persevere in the face of challenges both on and off the chess board. William Wheeler’s screenplay adequately displays Katende’s internal moral struggle that eventuates in his rejection of an offer to undertake a successful engineering career to instead coach a team of social outcasts — i.e. Uganda’s despised poor children.

Lupita Nyong’o effectively executes the role of Nakku Harriet, the mother of the film’s titular character and the atypical matriarch whose faith and sacrificial love for her family grow despite a continuous and seemingly endless string of misfortunes that begin when her husband and the father of her four children dies unexpectedly. Newcomer Madina Nalwanga delivers quietly, yet forcefully as Phiona Mutesi, the alluded-to queen of the impoverished Ugandan province, Katwe. Nalwanga convincingly gives us a teenager caught in the formative years of life who establishes her figurative throne not by way of socially-acceptable physical beauty or by way of a handsome prince’s rescue… not even really because of her intelligence or keen moves on the chess board. Rather, the very Christ-like pattern of suffering, brokenness, and weakness mark the road that eventually leads to her emergence from abject poverty and obscurity into renown as a national hero and royal representative of her people.

Classic Storytelling and Unconventional Narratives

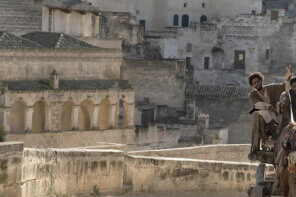

Nair’s direction collaborates with Sean Bobbitt’s cinematography to capture both congested metropolitan slums as well as the expansive, lush Ugandan countryside in which we see a panoply of darkly hued and beautifully complexioned people not from our Western world, but also not unlike us. They are human beings who have stories like we have; who have hopes, dreams, and disappointments like we have; whose city and nation have economic and class struggles like ours have. Though the film is touted as a sports movie and actually resembles a chess-version of 2006’s delightful Akeelah and the Bee, the real strength of the film lies in its honest portrayal of the everydayness of the everyday characters as they encounter challenges and work through the messiness of life under Adam’s curse (Genesis 3:17-19).

Though true to Disney form in its sentimentality and ultimate triumphant optimism, Katwe’s storyline resists becoming a moralistic fable about how “life is a like a game of chess.” Chess serves as the backdrop and context for demonstrating how unpredictable real life actually is. How despite our efforts at plotting our own courses and playing the proverbial game by the rules, we cannot control how God or life move the chess pieces. In a pivotal and illuminating moment preceding the film’s relatively climactic, yet predictable resolution, a mature Phiona (the film spans about 4 years of her life) opines to coach Katende that life cares nothing about our carefully planned strategies.

Though true to Disney form in its sentimentality and ultimate triumphant optimism, Katwe’s storyline resists becoming a moralistic fable about how “life is a like a game of chess.” Chess serves as the backdrop and context for demonstrating how unpredictable real life actually is. How despite our efforts at plotting our own courses and playing the proverbial game by the rules, we cannot control how God or life move the chess pieces. In a pivotal and illuminating moment preceding the film’s relatively climactic, yet predictable resolution, a mature Phiona (the film spans about 4 years of her life) opines to coach Katende that life cares nothing about our carefully planned strategies.

We, the viewers expect a 1-to-1 correlation between our protagonist’s wits and feats on the chess board and a picture of steadily inclining success in her personal life. We want a success formula and a visual aid that caters to and flows out of our penchant for wanting life to conform to easily identifiable and applicable rules and principles. What we get instead in Nair’s film is a picture of real suffering and consequently real faith — the kind that isn’t afraid to doubt and ask the questions believers are not supposed to ask about God and reality. Phiona wonders aloud during a crucial dialog sequence whether or not God has forsaken her and her family to which she receives a desperate and bleak reply that only reinforces the despair arising from a life afflicted by an eviction, consequent homelessness, ongoing tension between her mother and sister, and the eventual flooding of a temporary residence that nearly takes the life of her toddler brother, Richard (Ivan Jacobo/Nicholas Levesque).

Intercession and Identification with People

While widowhood forces Harriet to bear the burden of economically providing for and maintaining the cohesion of the family (and we see her extending ridiculous volumes of grace especially to her wayward daughter, Phiona’s older sister, who continuously dishonors the family and brings shame through her promiscuous lifestyle), Phiona must carry the weight of her city and her nation. A scene toward the end of the film during which two local girls approach Phiona as she practices her game in a café depicts our heroine as a salvific intercessor and federal representative more akin to Queen Esther (and ultimately, ahem, that one Nazarene….) than to Snow White, the idyllic, antiseptic, Eurocentric icon of the Disney franchise and epitome of all things “princess” in Western and more specifically American culture.

In the aforementioned scene, the young locals curtsy, refer to Phiona as royalty, and then implore her to compete in an upcoming game “for us” — i.e. for Uganda; for Katwe, the local province; for hundreds of poor girls… and boys who struggle to survive in an impoverished town where making bricks and selling wares in the marketplace consist of the daily grind. Phiona is a queen not unfamiliar with the sufferings and temptations and sufferings of her fellow Ugandans. She identifies with her people: she too lives in tents and slums; she too sells maize and produce in the market to help support the family; when she first meets the chess club, the other kids label her “pig” and deride her for being smelly. But like a kind of anointed “chosen one,” she bears a calling to win for her people — to put Katwe and Uganda on the map for something positive and noteworthy. Her victory and success will ultimately be theirs in a way not unlike the manner in which Jesus’ victory over sin, death, and the law is our overcoming and crowning achievement because of His having identified with our sorrows, griefs, temptations, and humanity.

A Flawed Queen

Mutesi is not however without flaws or character defects. At one point during the narrative’s development, we see royal hubris setting in as her string of successes renders her unwilling to participate in her usual household chores. The queen now shirks and snubs her expected domestic responsibilities on the grounds that such menial work is beneath the worth of a renowned chess champion. Incidentally, this scene treats us to a genuinely sweet moment of grace shared between our protagonist and her wounded, afflicted brother Joseph (Edgar Kanyike). The conceited national icon initially insists on keeping a candle burning so she can stay up late studying her chess manual in preparation for future competitions. Her little brother, previously injured by a reckless motorist, indicates he needs to go to sleep and thus asks her to extinguish the light. Phiona initially argues, ignores him, keeps the light going, and blows out her candle once she has become tired and ready for shut-eye. Humbly, the little boy extends his hand and relights her candle so she can keep studying! Yes, the child actors in this film are believable, adorable (without being trite), and genuine classic kids with whom your heart can connect!

Brokenness as True Beauty

Phiona’s deluded and arrogant self-opinion deflates quickly as a contest in Moscow against a formidable Canadian opponent evokes a fear in her that ultimately drives her to forfeit the match and to literally run through the city’s streets in tears. Reflecting on this moment later in the film, Phiona discloses that losing actually enabled her to win in life — to learn to accept life on life’s terms. Lutheran Theologians refer to this ability to deal with our world’s very broken reality as a Theology of the Cross. This theological distinction stands diametrically opposed to the Theology of Glory that sees God actively at work and blessing us only in favorable circumstances that find us happy, healthy, prosperous, and wealthy. Theologia Crusis on the other hand can call a bad circumstance a bad circumstance instead of naively and dishonesty glossing over tragedy with pious silver-lining phraseology. Cross theologians meet Jesus in the suffering… not in the absence or avoidance thereof. For the cross-theologian, suffering sobers us and forces us to accept the real version of life, not the ideal version we all wish were true where living well and doing right always earn you a seat at the breakfast of the champs.

Embracing the theology of the cross allows one to lose without being a loser… or rather to actually be a loser without losing one’s identity. We see this exemplified as Katende speaks identity into Phiona during the final chess match the film portrays. The scene is slightly cookie-cutter and bears the semblance of an afterschool special; however, what coach Katende shouts illustrates the impartation of identity from without the way the good news of the gospel comes to our wearied souls as a refreshing, external word of absolution emanating from an external source — not the swirling and confused vortex of our internal voices that damn us daily as we clamor to redeem ourselves through moral vigor and self-reflexive strength. An external voice, reminding Phiona who she is comes across loud and clear as Katende declares to an ambivalent and nervous Mutesi, “You belong here!” And of course, we are not surprised in this scene by the ensuing victory that finalizes her status as the queen of Katwe.

Embracing the theology of the cross allows one to lose without being a loser… or rather to actually be a loser without losing one’s identity. We see this exemplified as Katende speaks identity into Phiona during the final chess match the film portrays. The scene is slightly cookie-cutter and bears the semblance of an afterschool special; however, what coach Katende shouts illustrates the impartation of identity from without the way the good news of the gospel comes to our wearied souls as a refreshing, external word of absolution emanating from an external source — not the swirling and confused vortex of our internal voices that damn us daily as we clamor to redeem ourselves through moral vigor and self-reflexive strength. An external voice, reminding Phiona who she is comes across loud and clear as Katende declares to an ambivalent and nervous Mutesi, “You belong here!” And of course, we are not surprised in this scene by the ensuing victory that finalizes her status as the queen of Katwe.

Christ-centered, Cross-theology finds its greatest expression in the way the film skillfully handles this theme of belonging, identity, and home. The place of shelter where Phiona’s family finds refuge after their landlord evicts them apparently was once a church or a mission and in the heart of the interior sits highly on the wall a block-glass cross — the centerpiece of this family’s adobe-style home. A monsoon-like storm devastates their dwelling and awakens Phiona to the reality that she truly has no safe place to live life, as she confirms in a dialog with Katende where she mentions her fear of the street life engulfing her as it did her sister, Night (Taryn Kaze). The imagery of the flood mercilessly destroying the family’s makeshift living room despite the prominent presence of the cross-shaped window reminds us that the actual cross of Jesus retains no power or rather does not exist to shield our characters’ or our lives from tragedy.

The cross of Jesus Christ and our faith therein do not and cannot preclude us from experiencing the atrocities, inequities, and pain of this mortal existence. The Cross of Jesus does not ensure us a life free of difficulty, mystery, or grief. In fact, His Cross ensures a life filled with difficulty, mystery, and grief… but more fundamentally and essentially filled with Himself. The Cross gives us a sure, quiet, and steady hope that enables us to face reality, embrace loss, and most importantly retain identity knowing that while we are displaced in this broken and unpredictable world, we are always at home with the Father, in the Son. Fittingly, our story ends with the daughter literally bringing the mother… home. After a celebration erupts in the streets of the Ugandan city and after a brief scene in which we see a poster in a salon identifying Phiona as the official “Queen of Katwe,” the film’s coda gives us a touching scene in which Harriet’s children insist that she ride with them in a van to an undisclosed location outside the city’s limits. Once they arrive at their destination, Harriet asks, “Where are we going?” to which Phiona replies, “home.” At this point, we see the children lead her through a door into a beautifully remodeled and permanent house. Our characters make it home by way of suffering, affliction, and weakness… not necessarily because of unfaltering faith or perfect character. They make it home ultimately because of grace… and so will we because of One greater than Phiona who played chess with death and declared “Checkmate!” He’s the King of kings.