I should not be writing this review. I told myself I wasn’t going to write it. I told others I wasn’t going to write it. And yet, here I am – writing it. There are a number of things working against me. First off, I’m white. While the world was listening to a rap group called N.W.A, I was listening to a rap group called D.C. Talk. Here are some sample lyrics:

Word up people, we ain’t about sin no more

As a matter of fact

We cold boycottin’ sin right off the face of this Earth

Yo K-Max, you down with that?

(I’m steppin’ to that)

Yo T, you got my back on this boycott sin thang?

(You know it holmes!)

Word up sin, you are history!

Like I said, I shouldn’t be writing this review. I’m not familiar with gangster rap, I don’t know what it’s like to be a black person in America, and I have white privilege something fierce. But one thing I do know is movies, and movies always inspire me to write; especially the good ones. Straight Outta Compton is a good one.

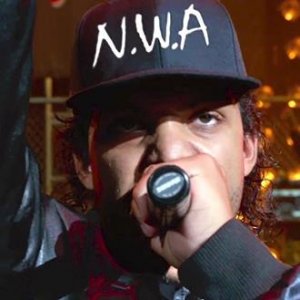

Raw Power

Compton is the story of five friends who grew up together in Compton, CA. Compton is still one of the deadliest cities in America, but back in the early 90’s the levels of police brutality, drugs, violence, and poverty were at an all time high. Out of this backdrop, the five friends formed a rap group called N.W.A. The group was an instant smash, but their friendships would be tested to the limits as ego and greed poisoned from within.

The cast is incredible. I didn’t recognize any of the actors in the film (outside of Paul Giamatti), yet the entire lot felt like seasoned veterans. Since the movie includes splices of the real life characters, we’re able to see how much the actors look like their counterparts. The resemblances are uncanny, but they also seem to capture the essence of the people they inhabit. The characters are what singlehandedly make this film work. We believe in these guys, despite their faults, and our emotions rise and fall in step with their careers.

But this is also a film about music, and on that front Compton doesn’t disappoint. I struggled to follow the lyrics, slang-filled as they are, but, really, lyrics aren’t the point. What director F. Gary Gray nails is the raw power of expression. I may not have understood the words, but I understood the emotions. I felt the explosion of anger and attitude as it passed from soul to mic. This is what it sounds like to grow up in a hell called Compton where violence happens every day and obscenity is a second language.

But this is also a film about music, and on that front Compton doesn’t disappoint. I struggled to follow the lyrics, slang-filled as they are, but, really, lyrics aren’t the point. What director F. Gary Gray nails is the raw power of expression. I may not have understood the words, but I understood the emotions. I felt the explosion of anger and attitude as it passed from soul to mic. This is what it sounds like to grow up in a hell called Compton where violence happens every day and obscenity is a second language.

Unfortunately, the movie suffers the fate of most biopics. The story feels bound to an internal checklist of incidents that keep it from truly soaring. Similar to book-to-film adaptations, biopics need to be released from outside expectations. What worked in a book might not work in a movie. What happened in real life might not translate to the screen. I wish Gray had cut out some of these incidents and let the characters breathe. But with performances and passion this powerful, the film remains a must see.

Vinegar and Fizz

Many will write off the music and characters in the film for their vulgarity. N.W.A’s lyrics are steeped in profanity, violence, and hate. And yet, so is Compton. This is all the group has known since they were in diapers. Why should we expect five guys “straight outta Compton” to act any differently?

We should never condone sin, but we should also have compassion for sinners. It’s one thing to declare the lyrics crude; it’s another to write off the group as less than human.

In the book The Shack, there’s a moment where God takes the form of a black woman bustling around a kitchen preparing a meal. She happens to be listening to rap music as she cooks. When the main character is surprised by this, she offers a powerful response:

“I listen to everything and not just the music itself, but the hearts behind it. Don’t you remember your seminary classes? These kids ain’t saying anything I haven’t heard before; they’re just full of vinegar and fizz. Lots of anger and, I must say, with some good reason too. They’re just some of my kids, showin’ and spoutin’ off. I am especially fond of those boys, you know.”

The Wages of Sin

One thing that impressed me about Compton was its honesty about sin. I expected honesty about sin’s pleasures, and there’s plenty of that. Anyone who tells you sin isn’t pleasurable is lying. Why else would we be tempted to do it? The film shows us the enticement of riches and fame. We see the allure of money as it starts to flow. We feel the intoxication of being worshipped by a room of thousands. We see the parties with scantily clad women ready to give their bodies away.

But then we see the consequences. We see the love of money begin to tear friendships apart. We see pride and ego lead to intimidation and abuse. We see a life of promiscuity end in disease and death.

God knows us inside and out. He created us after all. The commands he gives in Scripture aren’t arbitrary – they’re signposts pointing the way to life. Sin is pleasurable for a fleeting moment, but in the end it always leads to death. God isn’t trying to crash our party, he’s leading us to the real party.

Nothing Has Changed

I’ve heard some complain about the way police are represented in the film. I don’t understand why. This was the era of Rodney King after all. It’s not hard to imagine police brutality was a widespread problem. The real surprise is that it’s still happening today.

One scene stands out. The members of the group are talking outside their studio. Suddenly, the police show up and tell them to go home. When they refuse, the police force them all to the ground. N.W.A’s manager comes out of the building, irate. He explains who they are and tells his guys to get up. The policeman says “You don’t tell them when to get up. We tell them when to get up.” He pauses for a few seconds, smiles, and says “Now get up.” Racism is at play here, but also a love of power.

I’m reminded of the recent incident with Sandra Bland. Bland was pulled over for failing to use her turn signal. The entire police video of the stop is online. Everything goes smoothly until the police officer tells her to get out of the car. Bland refuses, saying she hasn’t done anything wrong. The officer gets livid. He tells her to get out of the car or he’ll force her out of the car. The situation escalates, resulting in Bland’s arrest. She died in police custody days later after committing suicide.

I’m reminded of the recent incident with Sandra Bland. Bland was pulled over for failing to use her turn signal. The entire police video of the stop is online. Everything goes smoothly until the police officer tells her to get out of the car. Bland refuses, saying she hasn’t done anything wrong. The officer gets livid. He tells her to get out of the car or he’ll force her out of the car. The situation escalates, resulting in Bland’s arrest. She died in police custody days later after committing suicide.

Let’s call a spade a spade – Bland died because when an officer told her to jump, she didn’t ask how high. She didn’t commit a crime. There was no reason for her to be in jail. This is an abuse of power.

Franklin Graham posted a message on Facebook to the black community telling them that they’re bringing this all on themselves. They should learn to obey and sort out injustice later. I hope I’m not the only one queasy at a white man telling black people to obey. This smacks of an era we’d all like to forget.

Black people are tired of being told to obey. If being bossed around by the police for no reason is a regular occurrence (and story after story tells us it is), can we fault them for growing weary? Bland should’ve been able to look that police officer in the eye and say “no, I’ve done nothing wrong.” He, in turn, should have stowed his pride and called it a day. Maybe then, black people will stop dying for forgetting to use their turn signal.

Pass the Mic

Gangster rap is a genre hard to understand. Maybe the problem is the title. “Gangster rap” was coined later on by the media. The group preferred the term “reality rap.” That cuts closer to the truth.

Judging N.W.A’s music on the surface is easy – their lyrics are profane. But that’s the power of Compton – it puts something difficult in context. It allows us to look beyond the words to the lives behind them. Something changes when you walk a mile in these artists’ shoes. Maybe we shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss what we don’t understand. Compton is a place where dreams go to die. Violence is everywhere. The police are the enemy. College is a pipe dream. Rap gave five disenfranchised guys a platform to speak their mind. Their music was a weapon of power for a city that was powerless.

As a white guy writing this review, I feel I’m once again part of the problem. Too long have white people been the dominant voice in our society. The time has come for us to stop and listen. We need to pass the mic.

In that vein, I’d like to give the last word to a rapper every bit as talented as N.W.A. Someone who speaks from experience, and knows what he’s talking about. Someone who happens to love Jesus. Yo Lecrae, take it away: