Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, film festivals have grappled with the same questions facing many businesses and non-profits. Chiefly, how do they keep the money pouring in?

We’ve seen many film studios largely switch to streaming platforms, allowing consumers unlimited access to their curated library of content for a monthly fee. Film festivals have followed suit, albeit in a more limited way. Anyone can purchase a virtual pass to many of America’s well-established festivals. However — and I can vouch from personal experience — the exorbitant cost of these passes often leaves working class film fans in the cold.

Sundance, arguably the most widely known film festival in the States, sought to get around this barrier by introducing a single ticket option. Viewers could purchase any number of limited streaming licenses for $15 and pick from the available screenings.

The tickets didn’t just get you access to the film, however. Along with premieres, consumers also received access to filmmaker Q&A’s and chat rooms with other attendees. It’s a fun wrinkle to the simple formula of “show up at such-and-such time, click the link, and finish the movie in two hours.”

I was able to scoop tickets for four of Sundance’s premieres. Here are my brief takes on each.

Eight for Silver (directed by Sean Ellis)

Midnight horror movies are a Sundance staple (or so I’ve been told), and the current trend of horror films taking on cerebral traits makes that angle a bit more complicated. Injecting horror with broader societal critiques is nothing new, but a more sociologically-educated audience likely demands more than treatises on family trauma.

Sean Ellis’ Eight For Silver tries to thread the needle between social horror and classic monster movie scares and succeeds — for the most part. Ellis was admittedly inspired by the mythology of the Beast of Gévaudan, and he brings the story into the text of the movie. It’s a savvy move, one which creates a meta-textual layer where the audience is forced to consider why horror stories exist in the first place.

It would seem irresponsible to leave out the fact that the inciting incident will be controversial to some. After all, a curse placed by a murdered Romani priestess is a trope that many movies have fallen on, leaving aside the historical atrocities committed against the Romani people. However, Ellis doesn’t shove these concerns aside, instead opting to show the massacre of a people group in what seems like real-time. Viewers are placed in the spot of a spectator, making them complicit with the violence taking place. It’s a bold move, one that sets a vengeful mood for the film ahead — and causes the audience to make an early value judgment on the characters.

Unfortunately, the film doesn’t always live up to the high standards set in the first 20 minutes. The performances are solid, especially in the margins. But Ellis fails to follow the standard set by Spielberg in Jaws when he shows the monster early and often. It doesn’t help that the creature effects feel a bit scrappy, giving the whole third act of the film something of a ramshackle feel.

It’s a pity, because the story beats work well in their own right. But when the characters are tip-toeing in the shadows, it’s hard to feel too nervous. We know what’s lurking around the corner. The fear of the unknown isn’t the only thing that contributes to a film’s scare factor, but it certainly would’ve amplified the movie’s core message. The entitled land “owners” are too self-absorbed to realize why they’re being hunted in the first place, even when the hunter tells them point blank. The sins of the father are corrosive in Eight For Silver, and the film seems to miss that one of those chief sins is narcissism.

Even with its flaws, however, Ellis’ midnight monster throwback does enough to earn the price of admission. It could probably do with some sanding around the edges, especially if it hopes to catch the eye of a distributor, but the vision feels fresh enough to satisfy horror-obsessives.

Grade: B-

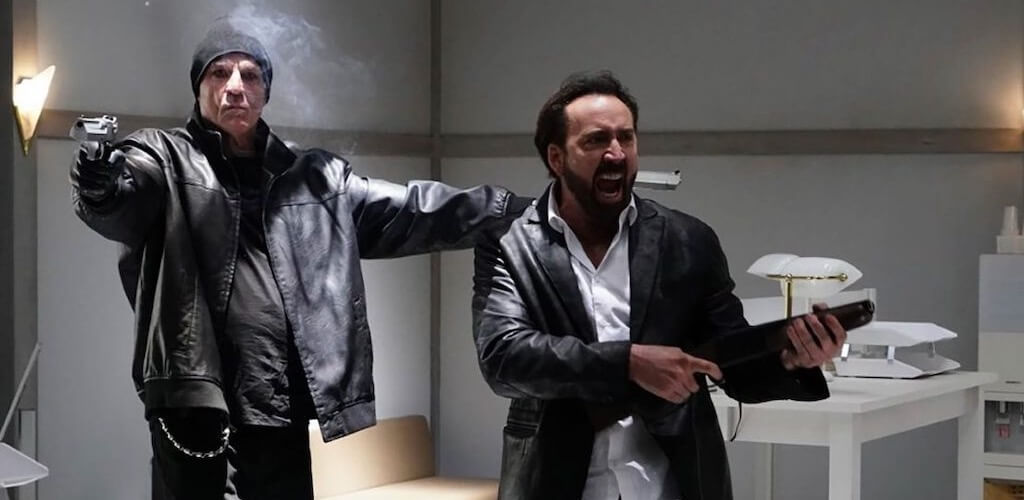

Prisoners of the Ghostland (directed by Sion Sono)

After years of capturing the collective film world’s imagination with his unrepentant streak of bad movies, Nicolas Cage has settled into something of a rhythm. No one would mistake it for a renaissance à la Matthew McConaughhey circa 2013. But Cage, and his knack for finding showy, polarizing genre work, has returned to a modicum of respectability.

This year, Cage runs his eccentric streak to Sundance, teaming with legendary Japanese filmmaker Sion Sono for Prisoners of the Ghostland, a cyberpunk western with elements of traditional samurai films and the smallest pinch of grindhouse. In a way, it’s almost teed up for film fans who have long been fascinated with what Cage will do next. After all, the festival’s promotional image shows Cage hollering maniacally and firing a shotgun.

But Prisoners, despite its director’s reputation, features the substance of a forerunning genre-bender without any of the substance. Between the clashing tonal performances (Bill Moseley feels like he’s in an animated series on Adult Swim) and the gratuitous but empty violence, Sono feels like he’s reaching for a vision in his mind that never quite translates to the screen. He does queue up some inspired sequences — Jim Croce’s “Time in a Bottle” scores one particularly memorable fight scene — but the whole of the piece turns out to be far less enduring once the credits roll and time passes.

As a film, Prisoners fails to fulfill the expectations it sets as its own hype machine. But there is something useful here, especially if you’re a cinephile continually fascinated by Cage and his antics. While the central performance certainly isn’t Cage’s most compelling, there’s a streak of world-weariness that has beset him. It injects his character with a sense of humanity that rarely crops up outside of the touching opening sequences of Mandy. Perhaps Nic Cage will never return to the mainstream levels of “respectability” that Hollywood requires of its A-listers. But as Cage shifts into the later stages of his career, there seems to be a grander story coming into play, one far more interested in themes of redemption, grief, and regret than his eye-popping, gore-infused choices of late would suggest.

Grade: C

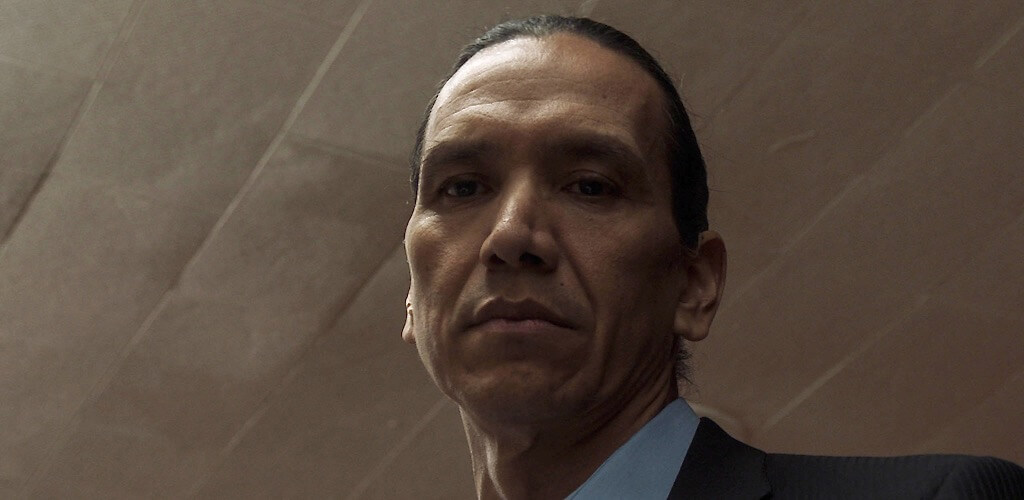

Wild Indian (directed by Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.)

One of the unfortunate parts about film festivals — and this will sound strange coming from a movie-based website — is how many films are actually a part of the program. Over-consumption of a thing leads to saturation, which can lead to dismissiveness. This is especially true with less-than-flashy films that occupy more meditative spaces — films like Wild Indian.

The feature debut of writer-director Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr., Wild Indian was never going to be the hit of a feel-good festival like Sundance. Corbine’s film is much too interested in the weight of ideas like generational trauma, self-loathing, and emotional indifference that begets violence. And while some critics have been quick to point out the film’s deficiencies (narrative clunkiness, underdeveloped ideas), Corbine more than makes up for them with his strong direction.

Capturing the story of two Ojibwe men harboring a dark secret, Wild Indian thrives as both a mood piece and a set of smaller character studies. Corbine uses barren woodlands and neutral-toned, blank home spaces to contextualize the inner-lives of the two leads, specifically as they grow into adulthood. Michael Greyeyes gets the majority of the screen time as Magwa, and he makes the most of it. Corbine allows Greyeyes the narrative space to work more forcefully, but Greyeyes takes a steelier approach, one that begets his character’s nature as a tormented tormentor.

Chaske Spencer as Ted-O is the real star, though, stealing nearly every one of his scenes. He too opts for a colder approach in the opening moments of his performance, but quickly transitions to something that is both humane and frighteningly raw in equal measure. The two actors play beautifully off of each other, and Corbine’s decision to let the performances breathe makes for a scintillating second act.

In the post-film Q&A session, Corbine remarked how Wild Indian was born from his own disconnection to his tribe. In the story, Corbine tells a tale that captures that disconnection by exploring how shame can spiral into something altogether more destructive, something that further separates us from the identity we were born into — perhaps even the identity for which we were created. It’s a staggering and near-oppressive introduction to such a young voice, but one that demands attention.

Grade: A-

Land (directed by Robin Wright)

Part of the Sundance “Premieres” catalogue, Land doesn’t carry nearly as much independent credibility as its festival comrades. That much is evident when the words “Focus Features” blaze across the screen before the title credits.

However, despite its big-money backer, Sundance’s spirit of discovery does seem appropriate for Robin Wright — yes, that Robin Wright — who collects her first feature directing credit. Stepping behind the camera isn’t new for Wright, who directed a number of episodes on her Netflix show House of Cards, but you can still feel the parachute lowering her to safety throughout much of her feature debut. The script is an easy-going two-hander with long stretches of no dialogue, allowing Wright to foist much of the film’s weight onto her own shoulders, shoulders that have proven more than capable over her decades-long career.

What makes the direction impressive, however, is how instinctual her choices feel. Perhaps it’s too generous to give her credit for shooting in the gorgeous vistas of Alberta, Canada, but Wright sees the strength of her film’s cinematography and leans heavily into it. Simultaneously, Wright deftly uses the film’s uneven script to her advantage, finding ways to mask its weaknesses (clunky dialogue, unearned minimalism) with her own acting talents. It helps that she’s placed opposite Demian Bichir, who gives a career-best performance as a fellow hermit who seemingly runs from demons of his own.

Yet despite what can sometimes be a predictable, formulaic exercise, Land largely works due to its complete and refreshing lack of cynicism. You could almost be tempted to think Wright’s film out of touch if not for the intense focus on an individual, rather than a societal, statement. World-weary characters retreating to nature isn’t a new path to tread, and rarely do thematic repeats excel without finding some new narrative angle to exploit. But Wright’s assured performance behind and in front of the camera, along with Bichir’s excellent supporting turn, wrestle Land from mediocrity to something short of an outright triumph.

Novelty isn’t always synonymous with excellence, and sometimes a story told well is, simply, a story worth telling. Land captures this spirit in the story of a grieving woman looking to, as Paul once said, “choose life.” A simple film for a simple message may not be exciting, but it is laudable.

Grade: B

__________________________________________

Without the benefit of a full pass, it’s impossible to say how well Sundance’s full program performed. Several of the festival’s more buzzy offerings (On the Count of Three, Passing, Coda) were sold out well before this writer could get access to them.

Still, it feels significant that Sundance has largely opened the door to a wider audience of filmgoers. They’re not the first to offer a virtual option, and they certainly won’t be the last. But if Sundance’s core spirit can be boiled down to “discovery” there would seem to be no better method than creating a program available to the scattered cinephile masses.

The films at Sundance? They were pretty good. The opportunity to participate from the comfort of your home? That’s pretty great.