If faith can give meaning to one’s life, conversely, losing the meaning of life can make one lose faith. We may look at the heroine of This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection, Mantoa, an old widow who first suffers from bereavement and then eviction with all her neighbors. In this plight, what does “resurrection” in the title refer to? As the saying goes “faith gives you strength” — can we think otherwise: how does faith lose its strength?

Lesotho is an African country enclaved by South Africa, and it is politically and economically dependent on the latter. Due to the colonial legacy, most Lesotho citizens are Christians, including the villagers in Nasaretha where Mantoa lives. The greatest joy of this old widow comes from the Christmas homecoming of her only son who works as a miner in South Africa, which is the moment when she can experience God’s mercy. But this time what returns is the news of her son’s death. In despair, Mantoa only wants to be buried with her ancestors after death in the village cemetery, but even this humble last wish vanishes because a damn dam project will flood this place. Although Mantoa once gains solidarity among all her neighbors, appealing to the authorities for withdrawing the project, what ensues are menacing arson and murder. In the end, during the exodus of the villagers, Mantoa suddenly turns back and removes all her clothes, walking towards the eviction cohort, naked and unashamed.

Problems of Pain and Evil

Facing the problem of human misery without resolution is as afflicting as misery per se, but it could be worse when you are offered certain ready-made sloppy answers. Mantoa is just a human being, not a “righteous person” as such like Job in the Bible. She experiences God’s mercy from her son, it’s natural she loses one after another. The village priest tries to show empathy, sharing his own experience of losing a beloved one, to testify that internal peace follows one’s complete surrender to God’s sovereignty — This is just meaningless to Mantoa who feels no comfort — perhaps God just doesn’t.

Tribulations come wave upon wave, making it impossible to imagine what is the worst case. When the bereaved Mantoa refuses to change her mourning dress after the grieving period, her neighbors think she has gone off the deep end, but actually, this is a sign of the death of the whole community. Later the villagers’ solidarity to protect Nasaretha once helps Mantoa to walk through the valley of the shadow of death, but this is just feeble light immediately obscured by the unbearable violence from above. Now the old widow can only bow down in the grave she digs for herself, vis-a-vis God’s silence.

Tribulations come wave upon wave, making it impossible to imagine what is the worst case. When the bereaved Mantoa refuses to change her mourning dress after the grieving period, her neighbors think she has gone off the deep end, but actually, this is a sign of the death of the whole community. Later the villagers’ solidarity to protect Nasaretha once helps Mantoa to walk through the valley of the shadow of death, but this is just feeble light immediately obscured by the unbearable violence from above. Now the old widow can only bow down in the grave she digs for herself, vis-a-vis God’s silence.

Problems of Modernization and Civilization

For Mantoa, the priest’s testimony and the Sunday service no longer have any meaning, perhaps not simply because of her misery, but that what the church testifies is mere emptiness. Although the priest does not represent all clergy, he is the only religious and intellectual representative, so he is the role model in the neighborhood. He is a good old man, but his obedience and endurance become less holy virtues than passivity towards the wickedness of worldly power, in the name of economic development. This eviction plot is based on real events in the past decades when the Lesotho government collaborated with South African and World Bank for several hydraulic engineering projects. These projects have forced many indigenous inhabitants to leave their homes and the natural resources for their sustenance. Hence the film throws a question to anyone who believes that obedience and endurance are inherent virtues, for if those imply surrendering to evil.

By questioning so-called “development,” the filmmaker Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese may also want to reflect on how Christianity, colonialism, and modernization have entangled with each other. Collaborations between religions and secular powers that obscure traditional cultures of local communities are nothing new. Originally this place was called The Plains of Weeping, as a remembrance of all the ancestors resting underneath the soil. The French missionaries came in the 19th century, as the harbingers of the European colonisers, renaming this place as Nasaretha. Now the dam project is going to unsettle the graves, agitating the dead souls, but also unearthing the collective memory passed on from generation to generation. Culture is always dynamic, and communal values are always in contention, but the question is: who has the say and who has to pay?

By questioning so-called “development,” the filmmaker Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese may also want to reflect on how Christianity, colonialism, and modernization have entangled with each other. Collaborations between religions and secular powers that obscure traditional cultures of local communities are nothing new. Originally this place was called The Plains of Weeping, as a remembrance of all the ancestors resting underneath the soil. The French missionaries came in the 19th century, as the harbingers of the European colonisers, renaming this place as Nasaretha. Now the dam project is going to unsettle the graves, agitating the dead souls, but also unearthing the collective memory passed on from generation to generation. Culture is always dynamic, and communal values are always in contention, but the question is: who has the say and who has to pay?

The Problem of Hope In an Absurd World

As the film starts, we know that actually Mantoa’s experience is retold by a storyteller in a dilapidated pub, narrating the past of “this place,” which implies that the beautiful vision of development often turns into dismal. Now the church bell rings and the villagers’ souls have all drowned underwater. Does this mean what we see happening in Nasaretha is the irrevocable reality, where all quests of meaning and faith are crushed by the wheels of development?

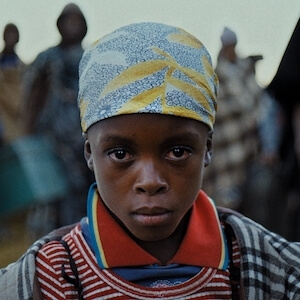

The end of the film just resists this fatalistic opening. Mantoa cannot change the facts about death and eviction, but she chooses not to yield. Although she forgoes violence and raises both hands in the air, she is not surrendering. This medium shot showing the skinny old widow from behind, walking fearlessly towards the “troop” of evictors, is the most powerful image in the film. The director does not show the consequences of her move against the oppressors — life or death — as he suddenly turns the camera 180 degrees from the heroine’s back to a little girl witnessing this important moment: this is the resurrection not from the dead, but the living ones. What does this mean?

The image of Mantoa’s back recalls Camus’s response to absurdity in The Rebel: “I rebel, therefore we exist.” Even though we cannot change the unjust reality, we still say “No” to it, as we are simultaneously saying “Yes” to other values, instead of falling into the abyss of nihility. The director’s interpretation of resurrection here also points to a new sense of hope, which does not simply refer to an afterlife — while prostrating oneself to absurdity in this life — but to testify that life can be renewed here and now.