In June I went to the library to pick up Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band, and while walking to the video section, I passed a display table of items in honor of LGBT+ Pride month. Perhaps it was a venial cynicism that heckled me from looking if The Boys were there, but after finding the movie under the Bs of Drama, I came back the same way, resolving to look. It did not have a spot at the table.

Boys has fallen in and out of favor since its premiere onstage, but other than during the initial run, it appears not many gay men consider it a point of pride. Perhaps I don’t either; pride has always seemed the wrong word with regards to any identifier, as it’s just as much of a vice as shame is a curse. And The Boys in the Band is about shame: how it is buried in and grows out of us and wraps around others, as if to keep our imbalance. It’s also about love. Yes, the love of gay men, from friends to lovers and between, but more importantly, it’s about a love, no matter how inconsistently sincere, that dares to speak the truth; an imperfect love that still casts out fear.

Since the Day One

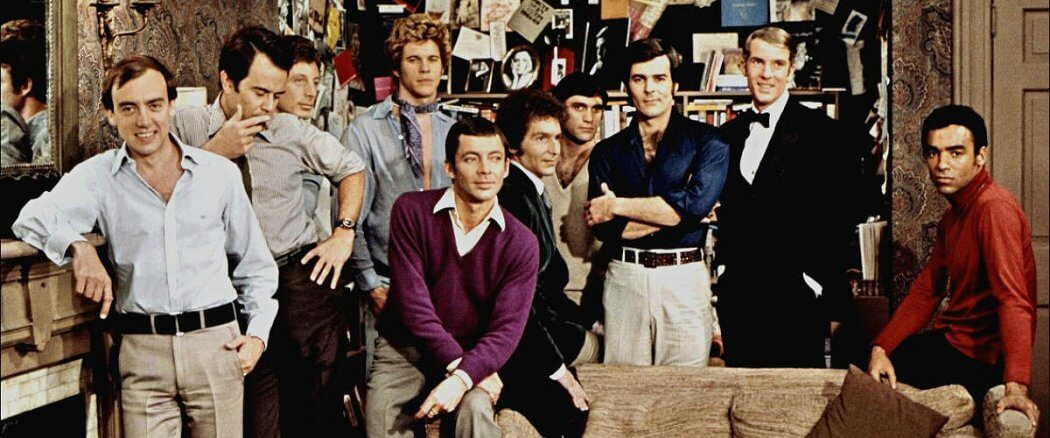

“Six tired screaming fairy queens and one anxious queer” who have known each other “since the day one” are gathering for a birthday party. The host is Michael (Kenneth Nelson), a lapsing Cathoholic with “counter-charm,” and the guest of honor is Harold (Leonard Frey), an “ugly, pockmarked Jew” with a sixth sense of humor. Alan (Peter White) wasn’t even invited, as he is too “square city” for this crowd, despite being a college roommate to Michael, who wasn’t out at that time. His arrival changes the group dynamic, or charges it, in ways that will affect everyone: Emory (Cliff Gorman), a “butterfly in heat,” to quote one of the few quotable insults; Bernard (Reuben Greene), a man of color whose emotional intelligence only increases the high cost of his kindness; Hank (Laurence Luckinbill), a math-teaching straight-passing divorcé who is in a relationship with Larry (Keith Prentice), despite the latter’s “sexual appetite” that is not satisfied by monogamy; and Donald (Frederick Combs), who reads books like others read the back of a cereal box, but still can’t get a read on himself.

These characters have been described as “a perfunctory compendium of easily acceptable [gay male] stereotypes,”* a statement difficult to reconcile with the fact that Boys was written by a gay man, the performances were given by mostly gay men and it was produced by gay men. Many are quick to bring charges of “internalized homophobia” without seeming to comprehend that externalizing it might be a solution, or the beginning of one.

Drama and Its Disguises

To Crowley’s recollection, three cords of influence braided together to form the Boys breakthrough: Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope and Stanley Kauffmann’s “Homosexual Drama and Its Disguises.” Kauffmann claimed that because “three of the most successful playwrights of the last twenty years are (reputed) homosexuals…postwar American drama presents a badly distorted picture of American women, marriage and society.” The remedy, Kauffmann posited, was to provide such a playwright with the freedom “to write truthfully of what he knows, rather than try to transform it to a life he does not know, to the detriment of others.”** Kauffmann’s argument is full of fallacies and prejudices, but rather than argue with it, Crowley wrote The Boys in the Band.

The play was an off-Broadway hit that ran for 1,001 performances and became a see-and-be-seen event. Soon Hollywood wanted to see some of those profits. Crowley believed the original stage director was the logical choice for bringing it to the screen, but the studio refused, so he went to director William Friedkin, based on the strength of his previous theatrical adaptation, The Birthday Party, by Harold Pinter. “One of the themes of [Pinter’s] work…” Friedkin explains in the DVD commentary, “is not that people can’t communicate and that’s why we are constantly at war or constantly fighting with each other, but that we communicate too well. No matter what is said by the other person, we read it and perceive it, we know what they mean. We know what’s behind their words.” With Pinter, it’s darting from behind one (Beat.) to another. With Crowley, it’s behind a clear and shiny membrane of wordplay, references and analysis, which some critics have misinterpreted as “crushingly obvious” and “[lacking] subtext.”*** But when you’ve been suppressed into subtext for most of history, once you get to the surface, you want to stay there for a while.

The play was an off-Broadway hit that ran for 1,001 performances and became a see-and-be-seen event. Soon Hollywood wanted to see some of those profits. Crowley believed the original stage director was the logical choice for bringing it to the screen, but the studio refused, so he went to director William Friedkin, based on the strength of his previous theatrical adaptation, The Birthday Party, by Harold Pinter. “One of the themes of [Pinter’s] work…” Friedkin explains in the DVD commentary, “is not that people can’t communicate and that’s why we are constantly at war or constantly fighting with each other, but that we communicate too well. No matter what is said by the other person, we read it and perceive it, we know what they mean. We know what’s behind their words.” With Pinter, it’s darting from behind one (Beat.) to another. With Crowley, it’s behind a clear and shiny membrane of wordplay, references and analysis, which some critics have misinterpreted as “crushingly obvious” and “[lacking] subtext.”*** But when you’ve been suppressed into subtext for most of history, once you get to the surface, you want to stay there for a while.

Time Disorientation

“Watching the film version of Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band…I experienced the same sensation I’d had when I saw the Off Broadway play two years ago,” wrote Vincent Canby, in a New York Times review from 1970. “It was a feeling of time disorientation, as if…I were looking at a well‐made Broadway play from the late thirties or early forties, something on the order of Clare Boothe’s The Women…” While Canby was correctly identifying one of the sources of Crowley’s style, he was also, understandably, unaware of gay culture at the time. The characters were based on the writer, his friends and acquaintances, who had “[their] own soundtrack, sartorial flourishes and short list of celebrity icons” that signaled a “boldness, irreverence, [and] independence.”**** When, as an early twentysomething, I first read Myra Breckinridge — another controversial gay masterpiece which was published the same year Boys premiered — I held the book in one hand and a pencil and notepad in the other, stopping to furiously scrawl the name of every film Gore Vidal referenced that I hadn’t seen.

The play took its cues from film and the film took its cues from the play.***** “Friedkin was not hired to improve The Boys in the Band, but to preserve it,” Canby wrote, but this is only partly true. “We decided early on not to go for stars,” Friedkin recounts. “We thought that the cast should be discovered by the audience. And I met all [the original cast] and I thought they were perfect, but that didn’t mean that you could take what they had done on stage and just film it…onstage you pitch your performance to…the last row in the balcony. It’s gotta be broader…So we spent a lot of time in rehearsal undoing the way they had played these parts onstage.”

Friedkin continues, “[A theater] audience decides what it will concentrate on…in a film, the director really decides what they’re going to look at. You make a kind of selection. And that’s very challenging…I’m still learning how to do that…not overdirect…make too many choices for the audience. One of the things I tried to do was keep a number of people onscreen at the same time. In different groupings.” The strategy is remarkably effective, sustaining a sense of interconnectedness and inescapability, vital to the tone of the piece. So, too, are the music and content of the title sequence: each character is introduced, with their own backdrops, which they can never quite turn their back on, for fear of what might happen. An old recording of “Anything Goes” transitions to a contemporary one, but we get a strong impression that times have not changed that much and anything does not go.

Friedkin continues, “[A theater] audience decides what it will concentrate on…in a film, the director really decides what they’re going to look at. You make a kind of selection. And that’s very challenging…I’m still learning how to do that…not overdirect…make too many choices for the audience. One of the things I tried to do was keep a number of people onscreen at the same time. In different groupings.” The strategy is remarkably effective, sustaining a sense of interconnectedness and inescapability, vital to the tone of the piece. So, too, are the music and content of the title sequence: each character is introduced, with their own backdrops, which they can never quite turn their back on, for fear of what might happen. An old recording of “Anything Goes” transitions to a contemporary one, but we get a strong impression that times have not changed that much and anything does not go.

Liberating Message

“[Boys in the Band] did serious damage to a burgeoning gay respectability movement among human beings in New York City,” Edward Albee declares. “That’s why I was opposed to it being produced.” Respectability politics can be a gamble, a grasping game of appealing to an established power, seeking to emulate its normative values and sublimate the differences of a marginal group. A movement that will not permit examination of itself and its population, even from an insider, sounds disturbingly similar to the oppression it is opposing. Whose respect do we need most? Our own.

In The Gay Metropolis, Charles Kaiser meditates upon one of the closing monologues. “Harold appears to be at his most vicious when he fires this parting shot at [Michael]: ‘You are a sad and pathetic man. You’re a homosexual and you don’t want to be. But there is nothing you can do to change it — not all your prayers to your God, not all the analysis you can buy in all the years you’ve got left to live. You may very well one day be able to know a heterosexual life if you want it desperately enough — if you pursue it with the fervor with which you annihilate — but you will always be homosexual as well. Always, Michael. Always. Until the day you die.’ On the surface, this speech is an assault on Michael’s malignant self-hatred. But hidden in the subtext is a surprisingly liberating message. Harold is proclaiming the immutability of homosexuality…[rejecting] the myth that homosexuality [can] be — and should be — ‘cured’…encouraging gay people to value themselves for who they [are].”

25 years after Boys opened, in 1993, the writer Richard Kramer prepared for an interview with Crowley by hosting a screening for the movie for gay men in their forties, thirties and twenties. The fortysomethings said, “We’re not like that anymore.” The thirtysomethings said, “We’re more like that than we’d like to admit.” And the twentysomethings said, “We’re just like that.”****** Like Meg in A Wrinkle in Time, whenever we shout the truth — or the lies we believe to be the truth — about ourselves, our traits, our desires, our mistakes — they lose a little more power over us. Well, the Boys shout, and at the right moment, in the right spot, it may cast something out of you, like a demon. It has for me.

__________________________________________

* The Celluloid Closet by Vito Russo, Harper & Row, 1981.

**The Gay Metropolis by Charles Kaiser, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997.

***Respectively, The Guardian and The New York Times reviews of the Broadway revival of The Boys in the Band.

****“The Extinction of Gay Identity” by Frank Bruni, The New York Times, April 28th, 2018.

*****“Movies are such garbage, who can take them seriously?” Donald proclaims, to which Michael replies, “Well I’m sorry if your sense of art is offended. Odd as it may seem there was no Shubert Theatre in Hot Coffee, Mississippi!”

******Metropolis, Kaiser.