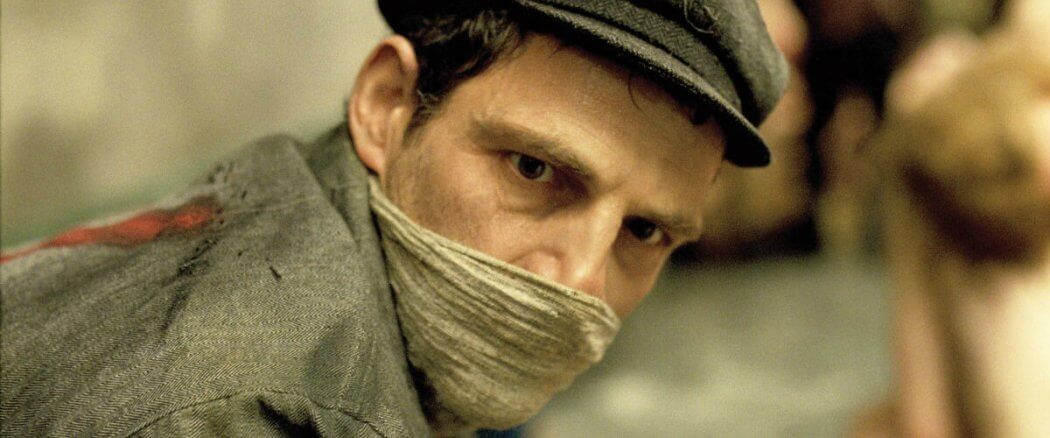

Son of Saul is a movie unlike any other I’ve seen. Critics agree. It has recently racked up an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, four awards at the Cannes film festival, as well as thirty-eight others. This is more than just another holocaust film. In fact it was intentionally made to be different than most films of its kind. Son of Saul is the story of an ordinary man’s strength to remain a man in the face of the some of the strongest force of dehumanization the world has seen.

Between Life and Death

As I alluded to above, Son of Saul is primarily the story of Saul. The screen is almost perpetually on his face or from his perspective. Almost all of the excessive or mundane horrors of the camp are blurred into the edges of the screen. Son of Saul is not primarily about the horrors of the holocaust. In fact, like Saul, I quickly became numb to it all. First and foremost this is a film about Saul the Sonderkommando, Saul the father, Saul the man.

As a Sonderkommando Saul’s job is to assist the Nazis in gassing his fellow Jews and then cleaning up and disposing of the bodies. Early on we see Saul performing his function, reassuring the newcomers, assisting as they strip and hang up their clothes, gently but firmly guiding the men and women into the showers. After their screams stop and the cleanup begins he finds a boy, gasping for breath, hanging between life and death.

As a Sonderkommando Saul’s job is to assist the Nazis in gassing his fellow Jews and then cleaning up and disposing of the bodies. Early on we see Saul performing his function, reassuring the newcomers, assisting as they strip and hang up their clothes, gently but firmly guiding the men and women into the showers. After their screams stop and the cleanup begins he finds a boy, gasping for breath, hanging between life and death.

Saul too is somewhere between life and death, fenced in by forced apathy to protect himself from his conscience. Ultimately he discovers a purpose in caring about this boy, to make him more than a body, and give him a proper Jewish burial whether it kills him or not. As he pursues his quest, taking bigger and bigger risks, getting closer and closer to dying himself, you realize this dead boy is his lifeline, his potential redemption from the indelible stain of his sins of survival.

A Different Hope

While Saul is resisting his role and executioners through this boy, his fellow workers are plotting an armed revolt. Bit by bit they are stockpiling weapons, trading for a bit of gunpowder, and waiting for the perfect moment. The whole of Saul’s interactions with them are tense and terse, with a low hum of anticipation in the background. I’m not sure how successful they expected to be, but at the same time they were taking illicit pictures and burying them with journals for whoever finally defeated the Nazis to know the truth, that they weren’t the same as their captors. Even if they couldn’t stop the Final Solution, someone would know they tried.

These men are occasionally actively hostile to Saul’s quest. His antics don’t only put his life on the line but sometimes directly harm their plans. Even when Saul’s not undermining their efforts, they want everybody focused and ready to charge with the signal, not off hunting for spades and Rabbis to bury one body among thousands. Leaving the theater I couldn’t stop thinking of their tension, their perpendicular means of seeking a parallel goal. Both efforts seemed doomed to do anything other than prove to themselves they weren’t truly complicit, to clean their hands of Jewish blood and ash by either dirt or Aryan blood. The men understandably fail to understand how anything short of taking up arms counts as rebellion, but it’s Saul’s quest that seems truly revolutionary.

These men are occasionally actively hostile to Saul’s quest. His antics don’t only put his life on the line but sometimes directly harm their plans. Even when Saul’s not undermining their efforts, they want everybody focused and ready to charge with the signal, not off hunting for spades and Rabbis to bury one body among thousands. Leaving the theater I couldn’t stop thinking of their tension, their perpendicular means of seeking a parallel goal. Both efforts seemed doomed to do anything other than prove to themselves they weren’t truly complicit, to clean their hands of Jewish blood and ash by either dirt or Aryan blood. The men understandably fail to understand how anything short of taking up arms counts as rebellion, but it’s Saul’s quest that seems truly revolutionary.

I am the last one who can cast blame on any of these men who are just trying to survive. That said, there is a different kind of hope in Saul, in the man who spends his life for another, who resists evil while holding on to his humanity. In an age that reflexively imagines resistance as a gun or fist, we are blessed to have a storyteller who brings us the story of Saul triumphing over the Nazis by keeping faith and honoring life in the heart of their death machine.