Paris Blues has many shades, but only one is visible to us: a whole crew wrote and rewrote the script, and in receiving the reports on these various drafts, there is much to mourn. Primarily, Sidney Poitier, “whose story this ought to be,”* dropping to third billing, after Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, cast as the white characters written in to attract their respective audience. And then there is the elimination of interracial romance, which Poitier identifies as the film’s loss of “guts” and “spark.”

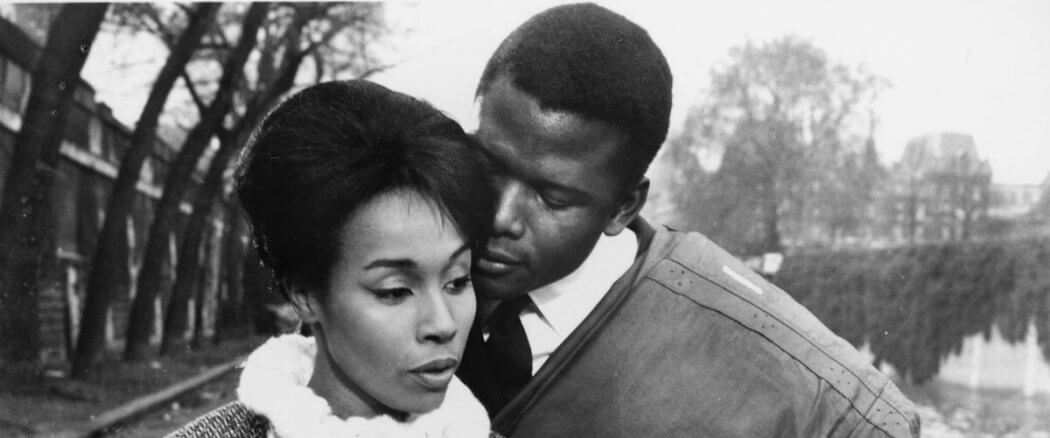

Poitier’s lament is valid, and furthermore, does not need my validation. Nevertheless, what was motivated by evil still resulted in some good, as “lining up the colored guy with the colored girl”** meant Poitier and Diahann Carroll stirred some serious romance, just one of many unrepresented black narratives in American cinema. “I understood the value system of a make-believe town that was at its heart a racist place…” Poitier recalls. “My unique relationship with each of the sides of the problem trapped me in one hell of a dilemma…I knew that however inadequate my step appeared, it was important that we make it…every new step would bring us closer.”***

Paris Blues brought us closer, but it is not just about race, it is also about vocation, or perhaps, how the former impedes and/or speeds our pursuit of the latter, and what sacrifices may be required. And despite some critical opinions to the contrary, it’s not muddled; it’s jazzy — naturally — in how it riffs around and gives everyone solos, even as they plainly need one another.

Love and Work

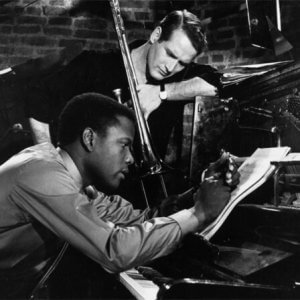

It’s Paris in 1961, where jazz is a lifestyle and Ram Bowen (Newman) and Eddie Cook (Poitier) are styling their lives around it: staying up late performing and composing, sometimes not sleeping, a profriendship. Eddie is black, and the only time it’s noticed in public is by a random child who politely calls him “Monsieur Noir.” They work at a club that’s radically hospitable — in crowd shots we see the young, old, rich, not so rich, interracial couples, gay couples, drag queens — for some you have to look carefully, but they’re all present, though that may be an attempt at penance for the film’s more significant compromises.

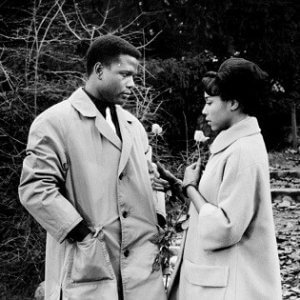

Lillian Corning (Woodward) and Connie Lampson (Carroll) are “day people,” friends and tourists visiting from America. Ram, who is at the train station to personally welcome celebrity musician Wild Man Moore (Louis Armstrong), observes Connie failing to communicate with a French porter and intercedes, resolving the confusion; in one of the film’s most interesting exchanges, Connie thanks him and mentions she’s waiting for a friend. Ram replies, “Is your friend as pretty as you are?” Connie apprises him, “Yes, she’s a white girl.” Ram deadpans, “She might be hard to find. All these white girls look alike.”

Lillian Corning (Woodward) and Connie Lampson (Carroll) are “day people,” friends and tourists visiting from America. Ram, who is at the train station to personally welcome celebrity musician Wild Man Moore (Louis Armstrong), observes Connie failing to communicate with a French porter and intercedes, resolving the confusion; in one of the film’s most interesting exchanges, Connie thanks him and mentions she’s waiting for a friend. Ram replies, “Is your friend as pretty as you are?” Connie apprises him, “Yes, she’s a white girl.” Ram deadpans, “She might be hard to find. All these white girls look alike.”

Ram continues the advances toward Connie when she and Lillian show up at the club that night. After a few lines of dialogue, it becomes clear Connie is not interested — or rather the screenwriters aren’t — but Lillian is. And so, the couples link up and loll about Paris, amidst a fabulous score by Duke Ellington and moody cinematography by Christian Matras and Martin Ritt, prompting curiosity about whether the film influenced Before Sunrise/Sunset and La La Land. There’s a lot of talking, and not talking, about work, love, the love we get from work, how we don’t expect love to be work.

A Swinger for the Cause

Connie is a teacher, and a “swinger for the cause,” so it isn’t long before she’s lecturing Eddie about his retreat to Paris and how he should return home to America, in a string of riveting scenes: “We do need our roots, don’t we?” Eddie isn’t feeling the loyalty. “Look. Here, nobody says ‘Eddie Cook, negro musician.’ They say ‘Eddie Cook, musician,’ period. And that’s all I want to be…And I don’t have to prove anything else…[like] because I’m negro I’m different. Because I’m negro I’m not different.” Connie is unmoved. “There isn’t a place on earth that isn’t hell for somebody. Some race, some color, some sex…I’m not denying what you feel…but things are much better than they were five years ago, and they’re gonna still be better next year. And not because negroes come to Paris.”

For Eddie and Connie, and of course, Poitier and Carroll, vocation is not just what they are called to do, but how they were created, in the sense that their work will be accepted, or not, through who they are. The fusion of identity and productivity — which Nilofer Merchant refers to with the term “onlyness” – is not an experience that most of us white people can really understand. In the case of Eddie and Poitier, it begets a “moral responsibility to uplift his race.”****

Why Do You Need Me Today

“I just wanted to tell you how much your music meant to me,” Lillian says to Ram, which Woodward accompanies with her passive yet penetrating gaze. “Thank you very much,” Ram replies. “I’m sure you hear that all the time,” Lillian scrutinizes his ego via her naiveté. “No,” Ram reflexes, “actually, you never hear that enough.” The dissociative “you” here confirms — along with other lines and the agonizing way he enables and disables a coke addict friend who is a guitarist his band — that Ram is dependent upon others’ approval. Preferably through his music, but if that fails, he will pivot to women. The owner of the club, Marie (Barbara Laage), with whom Ram is involved before Lillian comes to town, knows this. “Why do you need me today?” She queries him, softly and directly, in the film’s first scene. “Because you feel you’re wonderful, or because you feel you are worth nothing?”

“I just wanted to tell you how much your music meant to me,” Lillian says to Ram, which Woodward accompanies with her passive yet penetrating gaze. “Thank you very much,” Ram replies. “I’m sure you hear that all the time,” Lillian scrutinizes his ego via her naiveté. “No,” Ram reflexes, “actually, you never hear that enough.” The dissociative “you” here confirms — along with other lines and the agonizing way he enables and disables a coke addict friend who is a guitarist his band — that Ram is dependent upon others’ approval. Preferably through his music, but if that fails, he will pivot to women. The owner of the club, Marie (Barbara Laage), with whom Ram is involved before Lillian comes to town, knows this. “Why do you need me today?” She queries him, softly and directly, in the film’s first scene. “Because you feel you’re wonderful, or because you feel you are worth nothing?”

Maybe the most poignant example in Paris Blues of what people need is not any of the romantic relationships, but the friendship between Ram and his guitarist Rene Bernard (André Luguet). The two engage in real conflict due to some toxic patterns, but there is no question they are truly committed to each other and capable of change. This friendship is consistently overlooked in all the commentary, which reveals more about our culture’s view of companionship than it does the characters’.

A Step Taken

I was determined to write a rave of Paris Blues, to right the wrongs committed against it, because, as one viewer commented, “[it] puts me in the best mood.”***** Research can be a buzzkill. This film should have been a bold interracial romance, glowing through the smoke of jazz; whites should have been supporting characters; Poitier and Carroll should have met on this production as single people who began a marvelous courtship, rather than married people who began a covert affair; I should stop with the shoulds, which can’t even agree on what should be. Perhaps Paris Blues is as muddled as I refused to believe. Perhaps I’ll just take a cue from Poitier and count it as a step taken.

__________________________________________

*Stanley Kauffman, “The Talent of Paul Newman,” New Republic, October 9, 1961.

**Aram Goudsouzian’s Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

***Sidney Poitier, This Life, Ballantine Books, 1981.

****Goudsouzian, Sidney Poitier.

***** Ms. Alordayne Grotke @WesleyNicolee