I didn’t expect to feel tears stream down my face so shortly into Black Panther, but within the first few minutes of the film, I was already impacted heavily. In this reflection, I would like to touch on a theme of the movie that is presented within the first few minutes of the film. By doing so, I can avoid spoilers as well as lay out some initial thoughts.

[Editor: This is special guest post from Kyle J. Howard, a biblical counselor specializing in racial trauma. He is currently a student at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary finishing a graduate degree in Historical Theology and desiring to plant and pastor a transcultural church. You can follow Kyle on Twitter @KyleJamesHoward and listen to his podcast Coram Deo which focuses on issues concerning Biblical Counseling and Practical Theology. I’m personally thankful for his voice in matters of christianity and race and excited to share his writing with our audience. – Dan]

In the opening scene of the film, we see young black kids playing outside in Oakland, California. Inside, we see two men who are seemingly doing something criminal. Within seconds, we find out that the leader of the two men is N’Jobu (Sterling K. Brown from NBC’s family drama This is Us), brother to T’Chaka (South African actor John Kani) who is King of Wakanda. We are presented with two men with opposing worldviews, and it was the exploration of these worldviews which was a major theme in the film.

Wakandan Lives Matter

N’Jobu was living in America, not as a Wakandan, but undercover as a descendant of the African Diaspora (Black American). As he lived and moved as a black man in America, he became intimately aware of the pain and despair of those who lacked Wakandan privilege. He believed that the power, wealth, and privilege of the Wakandan people needed to be shared with oppressed black people who were living under the yoke of colonialism, oppression, and marginalization. King T’Chaka disagreed. T’Chaka didn’t consider black people outside of Wakanda to be his people. For the King, the only people who mattered were those within the borders of his own country. He wanted to keep Wakandan power and privilege within Wakandan borders, and ultimately he had no regard for people of African descent outside of those borders. So, despite having the ability to liberate black oppressed people groups around the globe, he refused to intervene.

N’Jobu was living in America, not as a Wakandan, but undercover as a descendant of the African Diaspora (Black American). As he lived and moved as a black man in America, he became intimately aware of the pain and despair of those who lacked Wakandan privilege. He believed that the power, wealth, and privilege of the Wakandan people needed to be shared with oppressed black people who were living under the yoke of colonialism, oppression, and marginalization. King T’Chaka disagreed. T’Chaka didn’t consider black people outside of Wakanda to be his people. For the King, the only people who mattered were those within the borders of his own country. He wanted to keep Wakandan power and privilege within Wakandan borders, and ultimately he had no regard for people of African descent outside of those borders. So, despite having the ability to liberate black oppressed people groups around the globe, he refused to intervene.

This dynamic in the film surprised me and it spoke to a tension I think many black Americans experience on a daily basis. We, the African diaspora, do not have a home. Our cultures, ethnicities, and even families were stolen from us. Not only were these things taken from our ancestors, new identities were imposed on us. When Africans stepped foot on American soil, they were given new identities. They were no longer Africans but became slaves. Their names were no longer culturally African, they were “Christianized”. We became Peter, John, and Toby and our only purpose for existence was to give our bodies wholistically to another to do with it whatever they desired. We became the cultureless. For centuries, these new identities were impressed on the diaspora. We would eventually be granted our humanity, but we would continue to live our lives daily questioning the value of our lives. Does black life matter? We did the best we could to create and cultivate cultures out of the fragments of our memories. We created Language, clothing, music, and dance all from the fragmented memories of cultural identities long murdered and scattered in the wind. As time went on, the chasm between black Americans and the land and cultures of Africa only widened. Black Americans have strived to hold onto a connection to Africa by embracing terms such as “African American” or by referring to Africa as “the Mother Land,” but the chasm has only widened and is felt in the hearts of most black Americans.

The Misrepresentation of Black Culture

As far as media and cinema are concerned, we have largely not had representation but misrepresentation. In media, we have been portrayed in a way that would perpetuate identity confusion primarily through elevating entertainers that have reinforced concepts of inferiority (drug dealers, criminals, fatherlessness, etc). On screen, we are celebrated when we perform roles that demonstrate black inferiority. Denzel Washington was given an Oscar for portraying a murderous, crooked police officer. He was juxtaposed against a white rookie cop’s heroism. Halle Barry was given an Oscar for exposing her body to millions of viewers as she simulated sex and pretended to be a sex-crazed woman who needed desperately to be sexually ravaged by the white police officer who killed her black husband. Finally, Jamie Foxx won an Oscar over Will Smith’s portrayal of Ali by playing a womanizing musician who came from a broken black home.

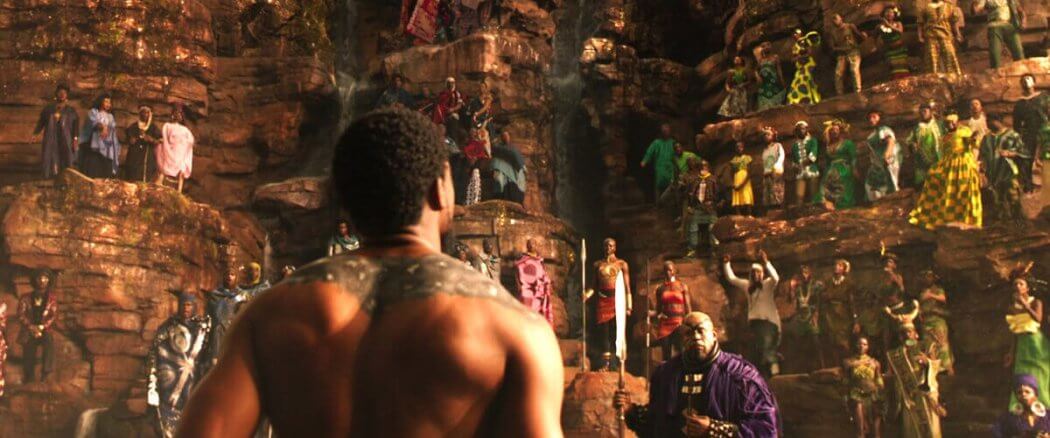

All of these realities serve as yokes placed on the shoulders of the black experience which leaves black people feeling lost and a lack of belonging. Then, the film Black Panther comes on the scene. At the start of the movie, N’Jobu laments the pain and oppression those the Black Diaspora has experienced. He speaks of them as being his people and within the first few minutes of movie, black Americans are told they belong. Black Panther is appealing to the black American community because it is an invitation to lift the veil and finally peer into where we came from, and in that, receive a sense of belonging. This place of belonging is of such beauty and excellence, that it adds to the affirmation of something that many of us have longed for, but rarely receive: the affirmation that we are valuable and are not forgotten. As a Christian counselor who has sought to serve the church faithfully over the past year caring for victims of race-based trauma I’ve lost count of the number of saints who have told me that the spaces they belonged to left them with much doubt as to whether their lives mattered. I myself have been a part of majority culture (white) contexts where I have had to live and move under a cloud of doubt as to whether my life mattered and if I was truly being received. Not only that, but often when black people gain a level of privilege and power in society, they often end up dismissing the oppression and marginalization of other black people and leave marginalized black Americans wondering whether their own kinsmen according to the flesh still care about them. King T’Chaka represents both black elitists as well as many other Africans who even today, dismiss black Americans rather than receive, empathize, and advocate for them.

James Baldwin once said “To be black and conscious in America is to be in a constant state of rage.” Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) represents the living embodiment of this quote. He is conscious as he intimately understands the black American experience as well as Wakanda’s dismissal of it. However, he is a man who has given himself over fully to the rage that comes with these understandings. The black American who has tasted or has known intimately the things I’ve described above will likely relate to Killmonger and even agree with him philosophically, and this is why he is such a well received villain. Killmonger is the black person many of us know we could become if we ever give into the daily rage of what being black in America produces. Killmonger is who I could become without Jesus. His rage and anger regarding the abandonment and betrayal of Wakanda could easily be me. Except my rage would be towards America — and the white American church.

James Baldwin once said “To be black and conscious in America is to be in a constant state of rage.” Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) represents the living embodiment of this quote. He is conscious as he intimately understands the black American experience as well as Wakanda’s dismissal of it. However, he is a man who has given himself over fully to the rage that comes with these understandings. The black American who has tasted or has known intimately the things I’ve described above will likely relate to Killmonger and even agree with him philosophically, and this is why he is such a well received villain. Killmonger is the black person many of us know we could become if we ever give into the daily rage of what being black in America produces. Killmonger is who I could become without Jesus. His rage and anger regarding the abandonment and betrayal of Wakanda could easily be me. Except my rage would be towards America — and the white American church.

A Love Letter for the Forgotten

The Black Panther film has been many things to many people. It has been a source of rage for many white people as they cannot stand the idea of black people being represented and affirmed. It has been a source of celebration for various African ethnic groups as their continent, and various cultures are displayed for the world to see. For the black American, it has been a long-awaited love letter from the people, cultures, and place they’ve longed to be seen and embraced by. It is a movie that concludes by affirming that black American people belong to Africa and that they are no longer a lost people, they are indeed African. Wakanda is not a fairytale world for black Americans to escape to for fun as they imagine dragons, wizards, and hobbits. No, Wakanda depicts a world and a people for them to remember, a world they have largely lost their connection to. Wakanda isn’t a place of sheer fantasy; it is a place of healing where black people can feel and imagine a sense of belonging and affirmation. Black Panther is a love letter to a people who feel forgotten, and it affirms their existence and value. It is a letter that says to black American women, “You are beautiful, strong, and esteemed.” A letter that says to black American men, “Your lives matter, you have dignity.” For children, Black Panther speaks and tells them that they are beautiful and worthy to be represented positively on screen.

For many of us, “Wakanda, forever!” means we have been changed and forever will be so. We have finally seen a picture of the world where we belong. We have seen a land imagined where the Diaspora never happened. We can close our eyes and imagine a world where our grandfathers weren’t lynched, where our women were not raped and enslaved, and where our men were not tortured and bound. We can imagine a world where black lives matter and where we can live while not under the “white gaze”. We can also imagine a world where our African ethnic ancestry is still intact, and we no longer have to wonder where we came from and where we belong. When we say, “Wakanda, forever” we are not simply expressing the delight that comes from a fan of a mythical world, we are expressing a joy that comes from being found, being seen, and being valued.

Finally, Black Panther speaks to the hope of restoration and healing that is ingrained in every human soul. God has placed eternity in the heart of image bearers, and in the heart of the oppressed there is a hope of one day no longer being weighed down. Black Panther massages this hope in the imaginations of the African Diaspora. It presents a shadow of God’s promise in Revelation 21:1-4, “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away.'”

Wakanda, Forever.

Kyle J. Howard