Social justice advocate and attorney Bryan Stevenson has stated that Americans need to greatly challenge the present narrative on race that has historically informed the way our criminal justice system functions primarily with regard to the imbalanced and disproportionate imprisonment of people of color (particularly males). Stevenson, author of the bestselling nonfiction work A Just Mercy and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, opens and concludes Ava Duvernay’s provocative and informative documentary 13th available presently on Netflix. At 140 minutes in length, the film equally indicts post-Civil Rights era Republican politicians and their late 20th century Democratic counterparts for implementing policies that have historically served to functionally invalidate the very legal freedom and full societal inclusion the 13th (and indirectly also the 14th and 15th) Amendment promised liberated slaves immediately following the close of the Civil War.

A History of Racism

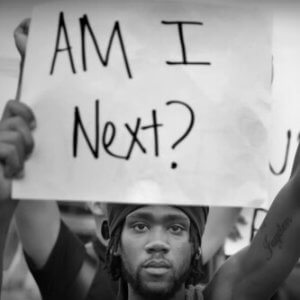

Duvernay argues that prior to the extremely influential rhetoric of presidential campaigns of the late 60’s, early 70’s, 1980’s, and even the most recent appeal to “make America great again,” late 19th century newspaper headlines overemphasizing black complicity in lawbreaking account largely for perpetuating the philosophy that empowers the present day Prison Industrial Complex (PIC). Though amorphous and intangible, the PIC exists as an ominous network of private economic interests that have colluded with lawmakers to influence policy regarding the manner in which our legal system identifies, processes, and imprisons many members of black and other non-white communities as dangerous inhuman criminals unworthy and incapable of actual reform or rehabilitation — it’s just more profitable to keep them locked up and separated from decent society.

13th ultimately though points to another very powerful source of inspiration for ongoing institutional racism: namely, D.W. Griffith’s 1915 technical masterpiece and official propaganda for white supremacy, Birth of a Nation. Duvernay’s film relies heavily at a critical point in the development of her argument on various clips of the film that caricaturize Black males as sexual predators hellbent on raping White women and causing civil disturbance. The film maintained such persuasive power that then-president Woodrow Wilson staged a special White House screening at which he venerated the deeds of the white Klansmen Griffiths portrayed as justly defending civilized white society from the disorder now present in America due to the abolition of slavery and the consequent period of Reconstruction. In fact, we learn in this documentary that the very practice of burning a cross derives from what Griffiths believed would serve as a visceral cinematic image.

13th ultimately though points to another very powerful source of inspiration for ongoing institutional racism: namely, D.W. Griffith’s 1915 technical masterpiece and official propaganda for white supremacy, Birth of a Nation. Duvernay’s film relies heavily at a critical point in the development of her argument on various clips of the film that caricaturize Black males as sexual predators hellbent on raping White women and causing civil disturbance. The film maintained such persuasive power that then-president Woodrow Wilson staged a special White House screening at which he venerated the deeds of the white Klansmen Griffiths portrayed as justly defending civilized white society from the disorder now present in America due to the abolition of slavery and the consequent period of Reconstruction. In fact, we learn in this documentary that the very practice of burning a cross derives from what Griffiths believed would serve as a visceral cinematic image.

But if media headlines, fear-inducing campaign ads, and idealistic silver screen rewrites of history have fueled already seething racial hatred and cross-cultural tension, there has also historically pervaded an artistic expression of a counter-storyline that quietly, yet consistently, seeks to refute the narrative that even black people have accepted about black people (please refer to Chris Rock’s hilarious, yet apt, insight on this matter in his 1996 classic standup special Bring the Pain). DuVernay’s film references the power of such alternative media in the latter half of the 1800’s as the printing and publication of autobiographical slave narratives such as those Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, and Booker T. Washington penned without censorship or editing regarding the horrors of slavery and the psychological battle to transcend such torment while retaining dignity and humanity. In later years, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his fellow Civil Rights activists would effectively employ the power of the television camera that often depicted the brutal dehumanization of protestors peacefully resisting and exercising justifiable civil disobedience while enduring abuse and harassment from law enforcement. The documentary twice pays homage to Mamie Till’s decision to publicize the graphic and gruesome photo of her disfigured teenage son, Emmett, whose only crime in 1955 was whistling at a white woman in a Mississippi diner.

Modern Day Voices

And of course, there’s Ava’s contemporary, actor-turned director Nate Parker who earlier this year produced an antithesis to Griffith’s national origin epic by sharing the same title, yet inverting the narrative. Where Griffith’s storyline aptly details the violence that fear drives one group of people to inflict genocide on another, Parker’s 21st century vision shows us the violence that precedes the redemption of a people who have historically responded to oppression (be it the horrific conditions of the slave plantation or the psychologically inescapable confines of the unjust prison system rife with its “mandatory minimums” and the stigma of “felon” that makes reentry nearly impossible) via artistic innovation and spiritual transcendence.

Incidentally, 13th, a film in which socially conscious hip-hop songs (the official art form of creative nonviolent protest and social commentary in urban America) punctuate interviews with politicians, corrections officers, professors, and sociologists, ends with rapper Common (whose Oscar-winning song Glory closed out DuVernay’s previous film Selma) issuing out a call of repentance urging America to come to Jesus. Employing insightful metaphors and appealing to historical sufferings of African Americans, the Chicago rapper’s Letter to the Free’s refrain also promises that it won’t be long before freedom comes. The Gospel informs us that freedom has come and will come again soon. His name is Jesus and He is the Word — the one true narrative that alone can restore the humanity of both the oppressor and the oppressed.