In Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film Pulp Fiction, grace invades an otherwise chaotic, yet legalistic realm in which the gangster’s code of honor apparently governs a world in which coincidental events punctuate a landscape inhabited by pontificating hitmen, washed up boxers on the take, and a conflicted professional who wrestles with his moral obligation to maintain a strictly platonic relationship with his boss’s wife…to whom he’s hopelessly attracted…and whom he incidentally ends up raising from the dead with the help of epinephrine and a reluctant drug dealer who resembles traditional artistic renditions of Jesus.

The film consists of three stories interwoven as one…all paying homage to the several film genres that shaped Tarantino’s creative mind in his formative years. This is the film that made me definitively decide to go to film school…or some semblance thereof in UW Madison’s Communication Arts department…Radio-TV-Film concentration to be exact. I literally wanted to be Samuel Jackson when I first ingested his inimitable delivery of embellished Old Testament Scripture in a context of vindictive rage all while channeling the sensibilities of Ron O Neal and Richard Roundtree alike! I mean, this film was like a mashup of Buck and the Preacher and Goodfellas for all I cared! It was magic, it was transcendent, it was pure poetry combined with the ineffable intimation of something otherworldly and…divine.

‘That was Divine Intervention!’ proclaims Jules Winfield (Samuel L Jackson) as he and Vincent Vega (John Travolta) evade bullets fired by a Jerry Seinfeld lookalike who unexpectedly emerges from a bathroom exclaiming ‘die, die, die!’ as he attempts to regain control of a situation that immediately escalates from Samuel Jackson’s casual sarcasm and invocation of trite cultural distinctions between French and American dining habits to a total ‘eye for an eye’ ‘I’m Gonna Git You Sucka’ type of tendency that undergirded the most prevalent of the very Blaxploitation films Tarantino grew up internalizing and adoring…even if he missed the deeper sociological implications and politically subversive messages embedded within.

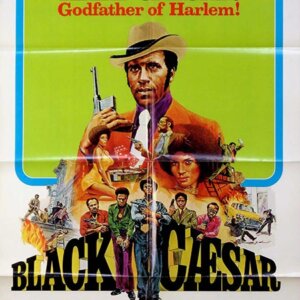

These films were empowerment vehicles in many cases for Black Americans who struggled through the uncertainty and disillusionment of the immediate post-MLK era. This was a time during which cinematic heroes emerged with names like Superfly and Black Cesar providing some sense of validation for the scores of African Americans still confronting the harsh realities of persistent disparities in education, housing, and access to employment that in many cases remain to this day. For example, one of the concluding scenes in the sequel, Shaft in Africa contains a convicting soapbox speech in which Roundtree’s John Shaft highlights the unfortunate parallels between the conditions of Africans residing in poor neighborhoods in France and the realities African American faced in the slums of New York ghettos. Or consider the social commentary espoused in songs like ‘Ghetto Child’ from the Superfly soundtrack or ‘Soulsville’ from the classic score Isaac Hayes composed for the original ‘Shaft’.

These films were empowerment vehicles in many cases for Black Americans who struggled through the uncertainty and disillusionment of the immediate post-MLK era. This was a time during which cinematic heroes emerged with names like Superfly and Black Cesar providing some sense of validation for the scores of African Americans still confronting the harsh realities of persistent disparities in education, housing, and access to employment that in many cases remain to this day. For example, one of the concluding scenes in the sequel, Shaft in Africa contains a convicting soapbox speech in which Roundtree’s John Shaft highlights the unfortunate parallels between the conditions of Africans residing in poor neighborhoods in France and the realities African American faced in the slums of New York ghettos. Or consider the social commentary espoused in songs like ‘Ghetto Child’ from the Superfly soundtrack or ‘Soulsville’ from the classic score Isaac Hayes composed for the original ‘Shaft’.

While Tarantino’s films don’t develop the deeper cultural significance of the very soul films he idolized, they do tend to bear glimpses of implicit gospel truth…especially Pulp Fiction…his most explicitly Christian-themed film to date. Forgiveness, redemption, and the irrational releasing of debts persist as the ironic threads holding together the interrelated vignettes that intersect idiosyncratic characters and the synchronicity by which their fates play out in a Shakespearean tragic-comedic manner. It is grace, not law, that ultimately rules in the Tarantino universe.

Gold watches and irrational grace

Al Green’s Let’s Stay Together cues the fade-in to a shot in which we view two characters arranged in one of Tarantino’s favorite devices – the confrontation, the interrogation, the standoff. Lifted from a pivotal moment in Jean Pierre Melville’s noir classic, Le Samourai, Tarantino often underscores the interaction between two characters working out a deal, in which the tables turn unexpectedly; resolving a conflict; or issuing a death sentence. In the opening of the chapter, ‘Marcellus Wallace’s Wife’, we enter where Marcellus Wallace, kingpin of the local crime syndicate, informs Butch Coolidge that he must forfeit an upcoming bout to ensure Marcellus wins bets he has placed against the has-been boxer. In the subsequent chapter, ‘The Gold Watch’ we learn that Butch’s pride supersedes in the decisive moment, and he instead slays his opponent, prompting him to go on the lam to escape his vengeful mob boss. Butch’s narrative is told through a lens of ridiculous and absurd antics as he inadvertently encounters Marcellus despite attempting to remain in exile at a motel with his girlfriend, Fabienne. After Butch and Marcellus tussle in the middle of a Los Angeles street, they find themselves captive in a sadistic underworld of human depravity, within the basement of a pawn shop where confederate fantasies of subjugated black masculinity and dehumanization abound.

While Marcellus is ‘violated’ by the pawn shop owners, Maynard and Zed, Butch ends up gaining the upper hand and escapes, though only momentarily. For some inexplicable reason, he pauses and returns to the scene of the crime to rescue the man who had put out a hit on his life. There’s no logical reason that Butch should intervene and save Marcellus from torture…just as there’s no apparent reason bullets evade Jules Winfield and Vincent Vega during the ‘divine intervention’ segment of ‘The Bonnie Situation’ (we’ll get there in just a moment). Furthermore, there is no logical reason that God should justify the ungodly (Romans 4:5), yet by His grace, this is exactly what does in Jesus Christ.

While Marcellus is ‘violated’ by the pawn shop owners, Maynard and Zed, Butch ends up gaining the upper hand and escapes, though only momentarily. For some inexplicable reason, he pauses and returns to the scene of the crime to rescue the man who had put out a hit on his life. There’s no logical reason that Butch should intervene and save Marcellus from torture…just as there’s no apparent reason bullets evade Jules Winfield and Vincent Vega during the ‘divine intervention’ segment of ‘The Bonnie Situation’ (we’ll get there in just a moment). Furthermore, there is no logical reason that God should justify the ungodly (Romans 4:5), yet by His grace, this is exactly what does in Jesus Christ.

Butch’s sudden change of heart reminds us that grace is erratic, spontaneous, and arbitrary in nature. Scripture connotes the grace of God as wind that blows where it wants to, though we cannot tell whence it comes or where it goes (cf. John 3:8). Furthermore, the grace of God upends our whole system of checks and balances, right and wrong, fair and unfair, reasonable and ridiculous, etc. Grace defies reason and logic and contradicts our better judgment. Or as St Paul put it in his epistle to the Corinthian church, “God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise” You know, foolish things like spontaneously deciding to forgive an enemy or arbitrarily choosing to rescue a man who is seeking to kill you. Such otherworldly wisdom truly reflects the sentiment in Romans 12 in which Paul quotes the book of Proverbs thusly,

If your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink. In doing this, you will heap burning coals on his head. Romans 12:20

After Butch rescues Marcellus from the pawn shop perverts, the renowned criminal overlord vows to ‘get medieval’ in his retaliation as he stands over Zed, holding the shotgun he used to ‘dismember’ his assailant. Butch consequently asks the theologically implicit question: ‘what now…between me and you?’ Marcellus replies, ‘There is no me and you…not no more’. The crime boss lowers his weapon (an implicit repudiation of right-handed power) and proceeds to lay down the conditions of Butch’s pardon, instructing him to exit the city permanently. Such a move reminds us of St. Paul’s words in the book of Romans in which he notes that through the sacrifice of Christ, there is no ‘me and you’ so to speak between us and God…not no more. We have been ‘reconciled to God through the death of His son’…and ‘there is therefore now, no condemnation’, nor any sin that separates us from Him. Paul expounds further in the book of Colossians that we were once at enmity with God, but we have through the violence of the Cross been reconciled…and the charges that stood against us per Divine decree have been eternally erased (cf. Colossians 2:13-14). There remains no more ‘bad blood’ between us and God…only the shed blood of His Son Jesus Christ.

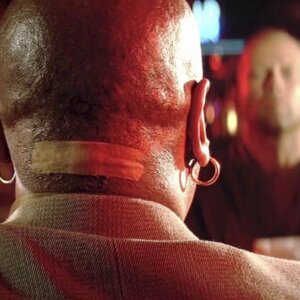

Butch stands in the basement doorway, slightly hesitant to leave until Marcellus raises his left hand in a gesture resembling the priests of the Old Testament extending their hands to officially bless the congregation after a sacrificial ceremony. What’s important to note concerning the staging of this scene is that during the dialog exchange between Butch and Marcellus, the latter keeps his back toward Butch, who remains in the background. When we see Marcellus raise his hand to ratify Butch’s pardon, we only see his back. This is significant because when we first see him in the film, the only view we have is the back of his head, replete with the band-aid on his neck that has sparked countless internet rumors implying Marcellus’ soul is in the film’s mysterious briefcase!

Indeed, the tables have unexplainably turned. When we initially see the back of Marcellus’ head, he is exploiting Butch for financial profit. When we see his back at the close of this chapter, he is granting Butch his freedom. Tarantino shows us a world in which random, yet synchronous events imbue our ordinary, banal existence: Butch ‘happens’ to gain the advantage on Vincent Vega when he returns to his apartment to retrieve his father’s gold watch; afterward, he ‘chances upon’ Marcellus as he is crossing the street; an innocent bystander ‘happens’ to get shot by a stray bullet when Marcellus fires at Butch in the middle of an intersection; Butch and Marcellus ‘happen’ to stumble into this sordid pawn shop and became victims of sexual assault; Butch ‘happens’ to have a change of heart…

Indeed, the tables have unexplainably turned. When we initially see the back of Marcellus’ head, he is exploiting Butch for financial profit. When we see his back at the close of this chapter, he is granting Butch his freedom. Tarantino shows us a world in which random, yet synchronous events imbue our ordinary, banal existence: Butch ‘happens’ to gain the advantage on Vincent Vega when he returns to his apartment to retrieve his father’s gold watch; afterward, he ‘chances upon’ Marcellus as he is crossing the street; an innocent bystander ‘happens’ to get shot by a stray bullet when Marcellus fires at Butch in the middle of an intersection; Butch and Marcellus ‘happen’ to stumble into this sordid pawn shop and became victims of sexual assault; Butch ‘happens’ to have a change of heart…

Such ironic happenstance causes us to consider whether the Tarantino universe is guided by an ‘invisible hand’ that orders a precarious string of events. Or do strange occurrences just happen without any moral implications or existential meaning? Such is the substance of Jules and Vincent’s conversation at a diner, as Jules attempts to decipher the ‘why?’ behind the miracle he and Vincent experienced when the bullets missed them (more on this later). Scripture even poses this question, particularly in the book of Ecclesiastes in which, its author, ‘the Preacher’ (probably Solomon) considers the vast inequities of life. Solomon opines,

In this meaningless life of mine I have seen both of these:

the righteous perishing in their righteousness,

and the wicked living long in their wickedness.

So I reflected on all this and concluded that the righteous and the wise and what they do are in God’s hands, but no one knows whether love or hate awaits them.All share a common destiny—the righteous and the wicked, the good and the bad, the clean and the unclean, those who offer sacrifices and those who do not.

As it is with the good,

so with the sinful;

as it is with those who take oaths,

so with those who are afraid to take them.This is the evil in everything that happens under the sun: The same destiny overtakes all…

I have seen something else under the sun:

The race is not to the swift

or the battle to the strong,

nor does food come to the wise

or wealth to the brilliant

or favor to the learned;

but time and chance happen to them all.Ecclesiastes 9:1-3, 11

Indeed Holy Writ affirms that life is more or less a roll of the dice over which we have no control. And yet ultimately, these very random strands of existence culminate in grace. Later in Ecclesiastes, Solomon continues his ponderings, as he advises,

Ship your grain across the sea;

after many days you may receive a return.Invest in seven ventures, yes, in eight;

you do not know what disaster may come upon the land…As you do not know the path of the wind,

or how the body is formed in a mother’s womb,

so you cannot understand the work of God,

the Maker of all things.Sow your seed in the morning,

and at evening let your hands not be idle,

for you do not know which will succeed,

whether this or that,

or whether both will do equally well…Ecclesiastes 11:1-2, 5-6

In the New Testament, Paul expresses a similar sentiment when he writes to the Corinthians concerning their doubt of Christ’s resurrection. Invoking the plain witness of nature itself, Paul employs an agricultural metaphor as he affirms our imminent bodily redemption,

‘What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. When you sow, you do not plant the body that will be, but just a seed, perhaps of wheat or of something else’. 1 Corinthians 15:37-38

In the economy of God, ‘chance’ and grace are not necessarily mutually exclusive…neither are they diametrically opposed in Tarantino’s cinematic realm. While fortunes can change on a whim, and ironic reversals of power can occur unexpectedly, the proverbial tables often turn to show favor to the undeserving. It is such undeserved favor that gets the final word in this vignette as it does in God’s overarching narrative which finds resolution in the final book of Revelation. In fact, the final verse in the Bible consists of a benediction invoking the word ‘grace’ (Rev 22:21). Pertinent to this point are the insights of Bryan Jarrell from Mockingbird Ministries, who in his contribution to the tome, Mockingbird at the Movies, notes,

…as Butch leaves, he takes the keys to a motorcycle from one of the dead rapists. Riding as a free man to meet Fabienne, the audience can see the words ‘Grace’ emblazoned on the side of the chopper. Tarantino wants us to see an unselfish act of grace, where the empathy of one man leads to (admittedly temporary) the salvation of a second. Debts are cancelled, enemies are loved, and (some) sinners are forgiven. Is there a better name than ‘grace’ for a motorcycle ridden by a man who rescued his enemy?

The Wolf and the picture of justification

‘You callin’ the Wolf?….negro, that’s all you had to say!’, Jules says to Marcellus after the good news that help is on the way. After inadvertently shooting an informant (Marvin) from their previous hit job and splattering his brain matter on the interior of their Chevy Nova, Jules and Vincent seek asylum at Jimmy’s (Quentin Tarantino) house, which remains the only ‘friendly place in the valley’ within Marcellus’s criminal network. When they arrive, Jimmy doesn’t want to help them because their very presence in his home could jeopardize his marriage to Bonnie, after whom this chapter is aptly named, The Bonnie Situation. Jules contacts Marcellus who sends an enigmatic figure named “The Wolf” (Harvey Keitel) to the rescue. When he arrives, he introduces himself, “I’m Winston Wolf – I solve problems”. The Wolf represents help that arrives ‘from the outside’ which is exactly what Jules and Vincent stand in need of. Such external aid calls to mind what theologians call ‘alien righteousness’ by which the sinner receives deliverance from a source outside of himself – namely through the grace of Christ.

The Wolf’s mission remains simple: help Jules and Vincent cover up their sin – as in literally with the quilts and blankets he uses to drape over the seats of the appropriately named Chevy Nova – the etymology of which implies ‘new’. In fact, when Jimmy sees the patch job The Wolf has performed on the gangsters’ vehicle, he remarks, “I can’t believe it’s the same car.” Indeed, the miracle of redemption entails former things (like blood-stained auto interiors) disappearing as all things become new (2 Corinthians 5:17). The Wolf then orders Jules and Vincent to strip down to complete nudity in Jimmy’s backyard, in a scene resembling the botanical setting of Genesis 3 in which the first sinners attempted to conceal their nakedness with fig leaves but were instead clothed with the skin of a slain animal (a foreshadowing of the work of Christ). Both men appear for the first time in the film in a vulnerable position – bloody, messy, and naked as The Wolf sprays them down in humiliation. The motif of cleansing pervades The Bonnie Situation as Jules earlier chides Vincent for not cleaning his hands thoroughly and consequently staining the towels in Jimmy’s bathroom, making them resemble used maxi pads. We see this theme continue as The Wolf informs the two men that ‘stripping off those bloody rags is absolutely necessary’. Indeed, stripping off the filthy rags of our self-righteousness is absolutely necessary if we are to receive the righteousness that pleases God – i.e. the righteousness of Christ.

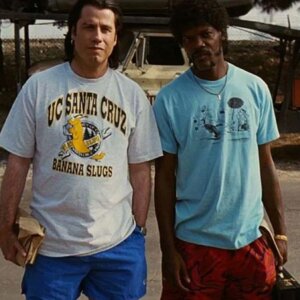

After their makeshift cleansing, Jimmy quips, ‘they look like dorks’, as we see the two hitmen dressed in Jimmy’s kitschy, novelty t shirts. It is notable that their hitmen attire is gone, having been indelibly stained with the guilt of their transgression (i.e. Marvin’s blood). Jules and Vincent are indeed covered with another’s clothing. Incidentally, it is while wearing someone else’s clothing that Jules will later extend grace, release, and pardon in the final act of the film.

After their makeshift cleansing, Jimmy quips, ‘they look like dorks’, as we see the two hitmen dressed in Jimmy’s kitschy, novelty t shirts. It is notable that their hitmen attire is gone, having been indelibly stained with the guilt of their transgression (i.e. Marvin’s blood). Jules and Vincent are indeed covered with another’s clothing. Incidentally, it is while wearing someone else’s clothing that Jules will later extend grace, release, and pardon in the final act of the film.

Jules and Vincent follow The Wolf to Monster Joe’s salvage yard, where they drop off the vehicle for disposal, like the priests in the Old Testament sending a scapegoat into the wilderness bearing the sins of the people. After junking the car, Jules asks the Wolf if everything is ‘cool’ now – i.e. are we off the hook, is the situation resolved, are we in essence forgiven? The Wolf casually responds, ‘like it never happened’. This is exactly how the doctrine of justification works in Christian theology. Those who are justified by the blood of Christ are credited as though they had never sinned or as the cliché states it: ‘justification is just if I’d never sinned’. How is this possible though? It is accomplished by the righteousness imputed to us through faith. This gracious gift credits us as though we had in fact always obeyed God because of the ‘obedience of Another’. St. Paul puts it this way in Romans 5,

The gift is not like the trespass. For if the many died by the trespass of the one man, how much more did God’s grace and the gift that came by the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ, overflow to the many! Nor can the gift of God be compared with the result of one man’s sin: The judgment followed one sin and brought condemnation, but the gift followed many trespasses and brought justification. For if, by the trespass of the one man, death reigned through that one man, how much more will those who receive God’s abundant provision of grace and of the gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man, Jesus Christ!

Consequently, just as one trespass resulted in condemnation for all people, so also one righteous act resulted in justification and life for all people. For just as through the disobedience of the one man the many were made sinners, so also through the obedience of the one man the many will be made righteous. Romans 5:15 – 19

As in Adam, we rebelled against the Creator, so in Christ, we have perfectly obeyed our Heavenly Father. Despite our attempts to justify ourselves through the works of the flesh and the several patch jobs we attempt to apply to the broken and messy parts of our lives, we have been covered in the perfect clothing of a righteous substitute. Though our best efforts at righteousness indeed amount to nothing more than filthy menstrual rags in the sight of God (Isaiah 64:6), there is a better sacrifice that clothes us, not with quirky t shirts bearing cliched phrases, but with the very flesh of God who beholds us in the light of His Son and sees our sin, ‘like it never happened’.

The path of the righteous man

Pulp Fiction’s most spiritually significant aspect is in the law/gospel tension that persists between the two scenes in which Jules utters the famous Ezekiel 25 sermonette. In God’s economy, the law always comes first bringing death, followed by the gospel which delivers a word of pardon, forgiveness, mercy and grace. The apostle Paul delineates these two words in 2 Corinthians 3, in which he reminds us, ‘the law kills, but the Spirit gives life’. In the film’s first act, the iconic monologue is delivered purely as a word of law resulting in death, as Jules executes the character, Brett in an act of vengeance on behalf of Marcellus Wallace.

Pulp Fiction’s most spiritually significant aspect is in the law/gospel tension that persists between the two scenes in which Jules utters the famous Ezekiel 25 sermonette. In God’s economy, the law always comes first bringing death, followed by the gospel which delivers a word of pardon, forgiveness, mercy and grace. The apostle Paul delineates these two words in 2 Corinthians 3, in which he reminds us, ‘the law kills, but the Spirit gives life’. In the film’s first act, the iconic monologue is delivered purely as a word of law resulting in death, as Jules executes the character, Brett in an act of vengeance on behalf of Marcellus Wallace.

Jules and Vincent show up at the apartment of Brett and his roommates, who are in possession of a mysterious briefcase that belongs to Marcellus. The two hitmen arrive as messengers of death not dissimilar to the depiction we see in the Old Testament account of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 19) in which God sends two angelic assassins to exact Divine judgment on His enemies. In Scripture, God often dispatches angels to carry out His vengeance on sinners. We see this in the book of Exodus when the Angel of Death administers a lethal plague on Egypt after Moses has repeatedly warned Pharoah to ‘let my people go’. We even see God sending angels in the New Testament to slay Herod in a manner that plays out like a scene in the Godfather (cf. Acts 12:21 – 23). It is worth noting that during the moment in which Jules and Vince riddle Brett with bullets, the two gangsters face one another like the cherubim who were positioned atop the holy ark of the covenant in ancient Israel. Incidentally, the briefcase itself resembles the ark as it retains an ethereal glow reminding us of its deadly power. Like the cherubim on the ark, Jules and Vincent guard a ‘sacred box’ by administering death to anyone who would handle it haphazardly (cf. 2 Samuel 6:1 – 7). Like the ark of the covenant, the briefcase was not to be desecrated, as Brett soon discovered when Jules laid the vengeance of God upon him.

In the film’s final act, the Ezekiel 25 speech is delivered as law and gospel.

Jules encounters ‘Pumpkin’ (Tim Roth), a petty thief who, along with his girlfriend ‘Honey Bunny’ attempts to rob the diner where the two hitmen reflect on the day’s occurrences, and debate whether they witnessed a bona fide miracle in Brett’s apartment. After Jules turns the tables on Pumpkin, whom he calls ‘Ringo’, he asks, “you ever read the Bible?…there’s this passage I got memorized”. Jules goes on to recapitulate the same ‘word’ that he had preached to Brett in the film’s prologue. The scene reflects the way God reiterates His word to contextualize it in grace, since the gospel is always his final word that He speaks to us. In his essay on Christian Liberty, Martin Luther alludes to this dynamic,

For not one word of God only, but both, should be preached; new and old things should be brought out of the treasury, as well the voice of the law as the word of grace. The voice of the law should be brought forward, that men may be terrified and brought to a knowledge of their sins, and thence be converted to penitence and to a better manner of life. But we must not stop here; that would be to wound only and not to bind up, to strike and not to heal, to kill and not to make alive, to bring down to hell and not to bring back, to humble and not to exalt. Therefore the word of grace and of the promised remission of sin must also be preached, in order to teach and set up faith, since without that word contrition, penitence, and all other duties, are performed and taught in vain.

We see a picture of this in the book of Jonah, who was considered a ‘minor prophet’ in the Old Testament. God commissioned him to go to the city of Nineveh (an enemy nation) to preach the word. In the first few verses of Jonah, God commands, “Go to the great city of Nineveh and preach against it…” The word functions as ‘law’ in this context as Jonah runs in the opposite direction in complete disobedience. St. Paul tells us that the law provokes not our obedience, but our rebellion (Romans 7:5). God sends a storm, and later a gigantic sea creature to cause the prophet to change his course…and his heart. Jonah eventually escapes from the whale and hears the same word from God that was initially given to him. This second utterance of the word, however, precedes not discord and confusion, but grace, mercy, and forgiveness as the entire city of Nineveh repents and escapes God’s wrath.

Jules reiterates the Ezekiel 25 passage that had initially brought death to Brett as the law is a ministry of death (2 Corinthians 3). This time, however, its recital occurs in a context of redemption. Having escaped death by what he considers to have been a miracle, Jules for the first time, ponders the implications of “the path of the righteous man being beset on all sides by the iniquity of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men”. He analyzes the verses in the text and surmises that Ringo is the ‘weak’ man who needs to be ‘shepherded through the valley of darkness’. At this moment, Jules who was formerly a vengeful minister of death, now serves a messenger of mercy, as he releases Pumpkin and Honey Bunny from the diner unscathed. Having resolved to leave the gangster life so he can ‘walk the earth’ like a nomadic mystic, Jules literally pays for Ringo’s soul by giving him $1500 from his personally ‘monogrammed’ wallet. Jules informs him, “I’m giving you that money so I don’t have to kill [you]”.

The one who recited the classic lines about the “path of the righteous man” to Brett, now informs Ringo that he has ceased from being “the tyranny of evil men” and is “trying real hard to be the shepherd”. In other words, the same words that under normal circumstances would have resulted in death, now precede permission to leave the scene of the crime blameless and without guilt. The message of the gospel reminds us there is a Law Giver who purchased our souls, not with $1500, but with the precious blood of a lamb without spot or blemish. The path of the righteous man is indeed beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Yet, there is One truly Righteous Man who bore our iniquities and offers us His grace. In Christ, we are not trying real hard to be the shepherd…despite our selfishness and the evil that resides within. We have been ‘restored to the shepherd of our souls’, and given a righteousness that comes from without.

The final moments of Pulp Fiction call to mind the exile of Adam and Eve from the garden of Eden in Genesis 3, in which God stationed cherubim to guard the way to the tree of life. Like Pumpkin and Honey Bunny, the first couple did not leave paradise empty handed. Instead, they departed with something greater than a cache of stolen wallets and a cash gift from a reformed hitman. The first sinners left with the very promise of redemption, as God vowed to one day send ‘the Seed of the woman’ to redeem the world. In the end, Pulp Fiction portrays a world in which nothing makes sense, yet everything makes sense, while grace reigns through the foolishness of forgiveness; debts are loosed for no good reason; and our attempts at interpreting divine omens are rightly mocked as ridiculous. It isn’t for us to mediate the invisible things – instead, The Word was made flesh to be the mediator between us and God. That very Word, who is ‘full of grace and truth’ came into the world with a message of salvation, not judgment. Having been judged in our place, He rose again offering us the freedom and redemption implied in the last word Jules speaks to Ringo as he releases him and says, ‘Go.’ The charity and goodwill he exhibits in this moment remind me of a greater Shepherd who is truly the finder of lost children, who gives us the right to be called children of God. In light of such good news, we too can freely ‘go’ because whom the Son makes free is free indeed.