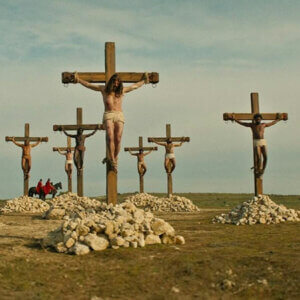

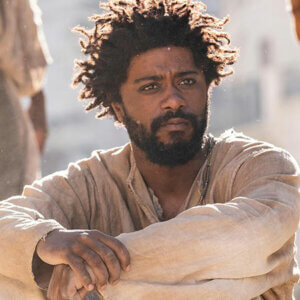

The opening shot of Jeymes Samuel’s Book of Clarence shows several criminals nailed to crosses per the first century Roman method of capital punishment. In the foreground, a white figure remains prominent, after which the camera maneuvers to concentrate our focus on the titular character portrayed by LaKeith Stanfield. After this, we see a credit sequence reminiscent of Ben Hur and similar “sword and sandal” flicks from that classic studio era when Jesus films (and related fare) abounded including titles like King of Kings, Greatest Story Ever Told, Quo Vadis. We then cut to Clarence and his best friend Elijah as they race chariots against Mary Magdalene. As they nearly run over a beggar whose presence shows up at key moments throughout the film, we are given a snapshot into Clarence’s indifference toward humanity, yet this film documents his journey from being an avowed atheist to becoming a genuine believer who inadvertently ends up doing some measure of good in the world.

The opening shot of Jeymes Samuel’s Book of Clarence shows several criminals nailed to crosses per the first century Roman method of capital punishment. In the foreground, a white figure remains prominent, after which the camera maneuvers to concentrate our focus on the titular character portrayed by LaKeith Stanfield. After this, we see a credit sequence reminiscent of Ben Hur and similar “sword and sandal” flicks from that classic studio era when Jesus films (and related fare) abounded including titles like King of Kings, Greatest Story Ever Told, Quo Vadis. We then cut to Clarence and his best friend Elijah as they race chariots against Mary Magdalene. As they nearly run over a beggar whose presence shows up at key moments throughout the film, we are given a snapshot into Clarence’s indifference toward humanity, yet this film documents his journey from being an avowed atheist to becoming a genuine believer who inadvertently ends up doing some measure of good in the world.

We find out that the chariot race was a means of earning enough money to repay a gangster known as Jedidah the Terrible (Eric Kofi-Abrefa) whose chariot and horse Clarence has borrowed and consequently lost in his failed attempt at clearing his debts. After Clarence is ambushed, we discover he is none other than the twin of Jesus’ disciple, Thomas (the Greek name Didymus means twin). After a confrontation with well, himself, (cf. Romans 7) in which Thomas accuses Clarence of being insignificant, Clarence embarks on a quest to prove that he isn’t a mere nobody and in fact has a place in this world. In order to accomplish this mission (and clear his debts with Jedidiah), he decides to supplement his um, shall we say ‘pharmaceutical enterprise’ by selling snake oil much like Elmer Gantry or Steve Martin’s character in Leap of Faith. Clarence comes up with a plan to become the 13th apostle, having been impressed by seeing the apparent glory and pomp of a disciple’s life during the scene in which Christ and His entourage first enter.

When he approaches the famed twelve disciples, they mock his request to join their group, yet Judas offers him a place in the ministry if he will prove his worth by freeing a group of gladiator slaves. Clarence accepts the challenge, yet only succeeds in freeing one of the slaves, an allegedly immortal champion named Barrabas whom he ends up befriending. While getting high on first century herbs with Eljiah, their friend Zeke, and newfound companion, Barrabas, Clarence gets an idea (a lightbulb literally appears above his head) in a scene that employs the magical realism pervasive throughout the film. Instead of striving to be a 13th apostle, why not instead become a new messiah? In order to pull this off convincingly, however, Clarence reasons he must visit the mother of Christ and learn the secrets behind the Nazarene’s miracles.

Faithfulness to the text

It is at this point where we see one of the more surprising aspects of a film that apparently had been marketed (and perceived by some) as sacrilegious parody. While I expected the satirical component (the trailer reminded me of Life of Brian and Buck and the Preacher), what I underestimated was how faithful to the faith the film remained in its portrayal of Christ (cf. Piero Pasolini’s Gospel According to St. Matthew). Alfre Woodard portrays Mary, the Mother of Jesus in a scene that affirms the very creed that establishes Christianity including the virgin birth, miracles, and the deity of Christ. Lest we mistake the scene’s comedic tone as mockery, the film condemns Clarence’s unbelief as he receives sharp rebukes from both Mary and Joseph when he questions the veracity of the aforementioned doctrines. This mirrors what we see when John the Baptist humorously chastises Clarence’s hypocrisy in a previous scene that takes liberties with the gospel account, without compromising its truth or being irreverent in its characterization of Biblical figures. The same John who slaps Clarence and condemns him for only wanting baptism for his own selfish motives, in the pages of Scripture calls the Pharisees insincere snakes whose religious piety is unworthy of the kingdom of God.

The Bible Through Black eyes

Despite the overall mediocrity of the film, I appreciated Samuel giving us a world of the Bible reimagined through a specifically Black lens. While there’s a precedent for this in the historical development of black theology and within African American cultural understandings of the Biblical story (consider Marc Connelly’s The Green Pastures [EDITOR’S NOTE: read our review of The Green Pastures here] or Virginia Hamiton’s The People Could Fly), there remains a paucity of such faithful representation in the history of Hollywood cinema. One of the main ways that white Supremacy has been perpetuated is via the enforcement of white images of Christ within popular media and within the artistic depictions that appear even in Black churches. Though I grew up in the predominantly Black environment of a Missionary Baptist Church, I can remember being genuinely confused as a child the first time I saw a non white illustration of Christ. I mean, everyone knows Jesus was white, right?

Despite the overall mediocrity of the film, I appreciated Samuel giving us a world of the Bible reimagined through a specifically Black lens. While there’s a precedent for this in the historical development of black theology and within African American cultural understandings of the Biblical story (consider Marc Connelly’s The Green Pastures [EDITOR’S NOTE: read our review of The Green Pastures here] or Virginia Hamiton’s The People Could Fly), there remains a paucity of such faithful representation in the history of Hollywood cinema. One of the main ways that white Supremacy has been perpetuated is via the enforcement of white images of Christ within popular media and within the artistic depictions that appear even in Black churches. Though I grew up in the predominantly Black environment of a Missionary Baptist Church, I can remember being genuinely confused as a child the first time I saw a non white illustration of Christ. I mean, everyone knows Jesus was white, right?

During the period of American slavery, the imposition of a white image of God served to reinforce the false notion of the slaves’ subjugation to whites and denied them dignity as image bearers. As a means of resistance, there has persisted in the African American freedom struggle the creation of our own churches, our own styles of preaching, our own narratives, our own worship services, even our own denominations, etc. Eugene Genovese for example implies in his classic tome, Roll Jordan Roll that slaves created and inhabited a religious world that insulated them from the violence perpetuated by imagery insisting that ‘white is right’ especially as it concerns the image of the Creator.

It was refreshing to see an inversion of the typical dynamic in a film that prioritized Black characters assuming lead roles within a biblical epic. Samuel clearly reveres the genre, while simultaneously attempting to subvert it. I just wish this subversion had been handled with more subtlety and nuance. The film had such tremendous potential to utilize the power of satire and social commentary to undermine a trope that has far too long defined a cinematic norm. Instead of providing thought provoking substance, Book of Clarence became encumbered by moments of crass humor and farcical elements that rarely rose above novelty. Satire can be effective, but this film lacked the provocation and engagement that would have made it a more developed analysis of societal issues the way comedians like Monty Python, Mel Brooks, and Dave Chappelle have done so well. The scenes that mirror our present social context (there are nods to racial profiling, police brutality, etc.) are mostly staged via soap box speeches and stock characters. In another instance, a worthy criticism of white Jesus mythology occurs in a scene that relegates the commentary to a silly dance number that eventually fizzles and just feels out of place in the overall development of the narrative.

Engaging culture and Christianity without losing the latter

When I came home from the theater, I remember glancing at my bookshelf and noticing titles like Lee Stroebel’s Case for Christ, and William McKissick Sr.’s In Search of Blacks in the Bible. Explorations of the reliability of the New Testament and the place of Blacks in the Bible were critical entry points for me when I first really engaged the faith nearly 25 years ago. Many of us Black Americans who follow Christ strive to understand how we can reconcile our cultural identity with our spiritual identity as we seek to “be in the world, yet not of it.” Furthermore, as disciples of Jesus who are called to “go into all the world and preach the gospel”, the perennial challenge concerns how we can engage culture without compromising “the faith once delivered”. Many attempts to do so have invariably created tension between efforts at revering ethnic heritage and confusing key aspects of the fundamentals inherent within the creed we profess.

When I came home from the theater, I remember glancing at my bookshelf and noticing titles like Lee Stroebel’s Case for Christ, and William McKissick Sr.’s In Search of Blacks in the Bible. Explorations of the reliability of the New Testament and the place of Blacks in the Bible were critical entry points for me when I first really engaged the faith nearly 25 years ago. Many of us Black Americans who follow Christ strive to understand how we can reconcile our cultural identity with our spiritual identity as we seek to “be in the world, yet not of it.” Furthermore, as disciples of Jesus who are called to “go into all the world and preach the gospel”, the perennial challenge concerns how we can engage culture without compromising “the faith once delivered”. Many attempts to do so have invariably created tension between efforts at revering ethnic heritage and confusing key aspects of the fundamentals inherent within the creed we profess.

It is inevitable that our handling of the Jesus Story, which as Mary informs Clarence, “is the only story,” will always be filtered through our unique cultural lenses. I can recall the juxtaposition I noticed at our local art museum between the Eurocentric baroque art displays of Biblical figures versus the religious imagery in the gallery displaying Haitian art. One would typically associate Haiti’s religious traditions with syncretism and non Christian folk religion, yet a particular painting of the crucifixion replete with distinct hues the artist used to convey the blood of Christ maintained a transcendent effect for me. Scripture wasn’t meant to be understood apart from one’s cultural context. It is indeed a heavenly book, yet it is also one that is very earthy – consider the references in the creation story to geopolitical locations like Ethiopia and Assyria; or geological references to the Euphrates river; or mentions of natural resources like gold, onyx, bdellium, etc. The Bible is divine, yet it’s a very human book, so much so that its author became human and so much so that its very conclusion depicts the integration of heaven and earth, and the reconciliation of humanity from every “tribe and tongue and people and nation”.

Grace ultimately prevails

The message of grace ultimately prevails in the Book of Clarence. When he starts his ‘ministry’ as the new messiah, Clarence resembles the character Hasil Motes from Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood (also a 1979 film by John Huston) as he persuades gullible crowds of observers that, “Knowledge is greater than belief.” Split screens and stylish cinematography aptly capture his internal conflict as he attempts to convince himself of his own hustle before deploying it on the unassuming masses before whom he and his disciples perform false miracles. Where Clarence differs from some of his cinematic predecessors is in the burgeoning change of heart he undergoes despite his best efforts to disprove the gospel message. Though he does end up earning enough money to repay his debts to Jedidah, he is moved instead to donate all the proceeds to purchase freedom for the remaining slaves he was initially unable to save during his first mission. Furthermore, his proclamation early on (while addressing the 12 disciples), “you believe in God, but I have real life knowledge there is no God” is eventually reversed when he finally informs Thomas, “I don’t believe; I know” as it concerns the reality of Christ. This occurs during the final act of the film after Clarence has been arrested for inadvertently performing a true miracle and is later sentenced to death for refusing to turn Jesus over to the Romans.

As Roman soldiers march Clarence to the place of execution, we see direct parallels with the New Testament’s account of Christ’s walk to the Cross. The film comes full circle as we observe the moment of crucifixion for Clarence, a traditional-looking white “Jesus” figure, and other enemies of the state. As he is dying, Clarence delivers a soliloquy in which he intercedes for humanity, noting, “We don’t know what we’re doing most of the time by the time we figure it out, it’s too late we need enlightenment, not punishment”. His words which resemble Christ’s cry from the cross, “forgive them, for they know not what they do” represent an apt assessment of our human condition and our need for grace rather than Divine wrath. Samuel’s film implies that enlightenment in itself isn’t sufficient to save us though (cf. Genesis 3:5-7). Such a term remains a buzz word often used to relegate Christ to being a human who simply arrived at a higher level of consciousness than the average individual. Yet, Samuel gives us both a historical and Biblical Jesus who incidentally performs an actual bodily resurrection. In the film’s final moment, Jesus raises Clarence from the dead much like the miracle He performed on Lazarus in the gospel account by St. John. When he rises, the lightbulb we had seen earlier in the film reappears above his head. The enlightenment he sought is replaced instead by a full, physical resurrection. Clarence is a stand-in for all of us who seek our own glory. We think having power, renown, and control will finally make us somebody in life and in the real world. Instead of the enlightenment we think we need, God gives us a resurrection that exceeds our expectations through a Savior who bears our iniquities. While this final scene remains ambiguous in what it signifies, resurrection gets the last word in the story Jeymes Samuel tells. It also happens to be the final word in the story God is telling which, as Mary reminds Clarence and all of us, “is the only story.”

As Roman soldiers march Clarence to the place of execution, we see direct parallels with the New Testament’s account of Christ’s walk to the Cross. The film comes full circle as we observe the moment of crucifixion for Clarence, a traditional-looking white “Jesus” figure, and other enemies of the state. As he is dying, Clarence delivers a soliloquy in which he intercedes for humanity, noting, “We don’t know what we’re doing most of the time by the time we figure it out, it’s too late we need enlightenment, not punishment”. His words which resemble Christ’s cry from the cross, “forgive them, for they know not what they do” represent an apt assessment of our human condition and our need for grace rather than Divine wrath. Samuel’s film implies that enlightenment in itself isn’t sufficient to save us though (cf. Genesis 3:5-7). Such a term remains a buzz word often used to relegate Christ to being a human who simply arrived at a higher level of consciousness than the average individual. Yet, Samuel gives us both a historical and Biblical Jesus who incidentally performs an actual bodily resurrection. In the film’s final moment, Jesus raises Clarence from the dead much like the miracle He performed on Lazarus in the gospel account by St. John. When he rises, the lightbulb we had seen earlier in the film reappears above his head. The enlightenment he sought is replaced instead by a full, physical resurrection. Clarence is a stand-in for all of us who seek our own glory. We think having power, renown, and control will finally make us somebody in life and in the real world. Instead of the enlightenment we think we need, God gives us a resurrection that exceeds our expectations through a Savior who bears our iniquities. While this final scene remains ambiguous in what it signifies, resurrection gets the last word in the story Jeymes Samuel tells. It also happens to be the final word in the story God is telling which, as Mary reminds Clarence and all of us, “is the only story.”