“The truth is the truth and should be spoken at all times,” proclaims Grandma Martin (Estelle Hemsley), from the top of a stairwell, no less. It’s a bold mandate, especially arriving near the beginning, even for a script that boldly chooses some volatile subjects. But Hemsley, who also starred in the Broadway production of the play upon which the film is based, pronounces the line with prophetic authority. She knows Take a Giant Step does just that.

Coming of an Age

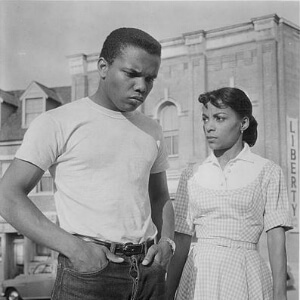

Spencer Scott (Johnny Nash) is a black high school senior on the south side of a New England town that is almost exclusively white, in population and policies. When one of the teachers, Miss Crowley, implies slaves were of limited intelligence and therefore incapable of changing their condition, Spence stands and stares at her. Crowley asks if he has something to say. “I might have a lot of things to say,” Spence retorts, “if I didn’t have to say them in the company of such dumb jerks.”

The teacher is not pleased; nor is the principal or Spence’s parents (Beah Richards and Frederick O’Neal). Grandma Martin supports him, but over the course of the film, Spence will learn it is time to support himself. “The concept and writing are straight out of the Golden Age of Television,” writes Stanley Kauffman, in an insult made of questionable memory, poor judgment, and clear bias. Certainly, Giant Step is not without some convention and the occasional overwrought moment, but then, what adolescence isn’t? Ultimately, it’s not only about coming of age, but the coming of an age; a period in which the “limitations placed on the construction of the African [American’s] racial consciousness…sexuality and expressive use of language”* would be challenged.

Caught All By Ourself

“We all of us somehow caught. We born this way or that way and we don’t know why…And maybe we wants to widen and bust free. But no matter what we do we still caught. Me is me and you is you and he is he. We each one of us somehow caught all by ourself…” Berenice, a servant, tells the children in The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers. “I’m caught worse than you is…Because I am colored…They done drawn completely extra bounds around all colored people. They done squeezed us off in one corner by ourself…Sometimes a boy like Honey feel like he just can’t breathe no more. He feel like he got to break something or break himself. Sometimes it just about more than we can stand.”

The passage is pertinent in itself, but becomes even more so upon discovering that Louis S. Peterson wrote Giant Step while touring with Member of the Wedding. Honey has to “break something or break himself” and Spence has to “hit himself with something” and Giant Step is Peterson’s swipe at oppressor and oppressed and how one can become the other. Early in the film, one of Spence’s white friends guiltily explains a neighbor “doesn’t like colored people…that’s the lousy truth…He just doesn’t like them.” Grandma Martin retaliates, “And I don’t like Polish people, either. Never have and I never will. Sometimes I think Hitler was right.” Spence whips around. “Oh cut it out, Gram,” he snaps, “you know Hitler wasn’t right, now what’d you have to go and say that for?”

The passage is pertinent in itself, but becomes even more so upon discovering that Louis S. Peterson wrote Giant Step while touring with Member of the Wedding. Honey has to “break something or break himself” and Spence has to “hit himself with something” and Giant Step is Peterson’s swipe at oppressor and oppressed and how one can become the other. Early in the film, one of Spence’s white friends guiltily explains a neighbor “doesn’t like colored people…that’s the lousy truth…He just doesn’t like them.” Grandma Martin retaliates, “And I don’t like Polish people, either. Never have and I never will. Sometimes I think Hitler was right.” Spence whips around. “Oh cut it out, Gram,” he snaps, “you know Hitler wasn’t right, now what’d you have to go and say that for?”

It’s a moment Peterson could have easily omitted for the sake of simplicity or sympathy. But he didn’t. He also didn’t cut a speech from Spence’s mother, effectively delivered by Beah Richards with a grief that flares into fury: “You are a little black boy and you don’t seem to understand it, but that’s what you are. You think this is bad? Well, it’ll be worse…you’ll do a lot worse. You’ll laugh at them when you feel like crying. You’ll smile at them when you could put knives right into their backs without giving it a second thought. And you’ll never do what you’ve done and let them know they’ve hurt you. They never forgive you for that.” The film industry wouldn’t forgive Peterson. At least not for awhile.

Black Heroism

It’s impossible to talk about Giant Step without talking about Raisin in the Sun, or to talk about either without talking about Big White Fog. Premiering in 1938, Fog is set in Depression-era Chicago, focusing on an educated black man and the beliefs that put him at odds with society and his own family. Fog created a structure for the modernist black family melodrama, which Giant Step continued in 1953 and Raisin in the Sun in 1959.** For a range of reasons, the former two don’t receive near as much attention as the latter.

And for Giant Step, one of those reasons is content. Spence’s confrontation of an authority figure, his rebellious language and developing sexuality were all uncomfortable for white audiences at the time, resulting in the MPAA’s refusal to approve the film and minimal effort from the distributors to promote it. Nevertheless, according to film and literary scholar Dr. Mark A. Reid, Giant Step was critical in “freeing black heroism from Hollywood’s social and economic restrictions.”*** The film’s audacity may have prevented it from receiving a wide audience then, and could still do so now, for those who are really listening.

Rough Goodness

The Sermon on the Mount is full of blessings for people that society has forgotten; it’s often cited as defense of God’s preferential option for the poor. Gustavo Gutiérrez, a founder of Liberation Theology, defines the phrase. “The very term preference obviously precludes any exclusivity; it simply points to who ought to be the first — not the only — objects of our solidarity. From the very first the theology of liberation has insisted on the importance of maintaining the universality of God’s love and the divine predilection for ‘history’s last.’”****

A film can’t move the last to first, but it can bring them forward for a few hours, which is what Peterson accomplishes, and more. His artistry — the script’s true reflectiveness — is its commitment to complexity, demonstrated most rivetingly by Grandma Martin’s interrogation of Spence’s parents, about two-thirds of the way through: “When you moved down here, did you ever stop to take into consideration that something like this was bound to happen, sooner or later? And that the most important thing might have been just your love and comfort? You did not. Went right on working. And instead of your company, he got a book, a bicycle, electric train…The stuff that came in this house was ridiculous…I don’t go along with that kind of raising, one way or the other.” Timeless wisdom of how socioeconomic privilege can impair priorities. In other words, “Blessed are the poor.”

A film can’t move the last to first, but it can bring them forward for a few hours, which is what Peterson accomplishes, and more. His artistry — the script’s true reflectiveness — is its commitment to complexity, demonstrated most rivetingly by Grandma Martin’s interrogation of Spence’s parents, about two-thirds of the way through: “When you moved down here, did you ever stop to take into consideration that something like this was bound to happen, sooner or later? And that the most important thing might have been just your love and comfort? You did not. Went right on working. And instead of your company, he got a book, a bicycle, electric train…The stuff that came in this house was ridiculous…I don’t go along with that kind of raising, one way or the other.” Timeless wisdom of how socioeconomic privilege can impair priorities. In other words, “Blessed are the poor.”

The blessings are mixed, to be sure. Spence has a “better” life, but at what cost to him and the family? He has learned how to deal with whiteness, but how has that discounted his blackness? “[Take a Giant Step has a] particular color, immediacy and urgency of its feeling,” writes Harold Clurman. “A kind of emotional frankness, a wry naivete and a rough goodness of heart that smack of something truly native, original in tone and unmistakably lived.” Indeed, Peterson lived most of Giant Step. It may not seem extraordinary to some, especially those who ordinarily have access to all society can offer. But Peterson was practicing his own revolution, armed only with the belt of truth.

__________________________________________

*Dr. Mark A. Reid, Jump Cut, no. 36, May 1991, pp. 81-88.

** Reid, Jump Cut.

***Reid, Jump Cut.

**** Systematic Theology: Perspectives from Liberation Theology by Gustavo Gutiérrez, Orbis Books, 1993.